Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland

August 12, 1921

It is already the case that the methods of observation, consideration and judgment that are otherwise customary today, according to the habits of thought that have developed over the last three to four centuries, cannot simply be applied to anthroposophical spiritual science. What is initially pointed to by intellectual concepts is actually only a kind of guideline in anthroposophy, to help us focus our observation of life and the world in the direction that will allow us to see reality, the full reality. Therefore, in the initial concepts of spiritual science, one has little more than a kind of scheme that draws attention to certain observation methods. These schemes are taken from the spiritual science that is to a certain extent complete, so that those who engage with spiritual science do indeed get something that may initially make sense to common sense, but which can only be fully understood when one brings what science and life otherwise give to these schemata.

One receives such a schema relatively early on when one begins to get to know anthroposophical spiritual science. And it is such a schema that guides us to look at the human being in such a way that we take the physical body, etheric body, astral body and I as the basis of this approach. In my book Theosophy, I immediately tried not to provide a mere scheme with these four elements of human nature, but to fill these abstract four concepts with a certain concrete content through the way they are presented there. So that to a certain extent - more can never be done - one realizes how justified it is to consider the human being according to these four categories.

But these things only come to life in a truly objective way when one enters into what is revealed in human life, in man's relationship to the world, and in the world in general, and then what the initially schematically defined concepts fill with a very specific content. From a certain point of view, we will try to do so again today.

We will start with what we call our self, insofar as we consciously experience this self, what this self actually represents. You know that this self as consciousness is interrupted in the course of life by all the states that occur between falling asleep and waking up. With the exception of dreaming, and actually to a certain extent even during dreaming, this sense of self is lost for the time between falling asleep and waking up. We can say: this sense of self is always kindled at the moment of waking up – whereby, of course, kindling is only an expression used in a figurative sense – and it fades away at the moment of falling asleep.

When we develop the ability to observe such things, we notice that this sense of self, in the narrowest sense, is bound to the whole range of sensory perceptions, but actually only to these. You only have to carry out a kind of experiment on the soul, which consists of trying to erase all sensory content while awake, to refrain from all sensory content, so to speak. We will return to this later from a different point of view. But you will notice when you try to refrain from all sensory content that in the vast majority of cases and in the vast majority of people there is a certain tendency to sink into a kind of sleep state; but that means, precisely, to dampen the I. You can see that the sense of self, as it prevails in waking hours, is essentially linked to the presence of sensory content. So that we can say: we experience our ego at the same time as the sense content. We actually do not experience our ego for everyday consciousness other than with sense content. As far as sense content extends, ego-consciousness is present, and as far as ego-consciousness is present, at least for ordinary life, so far sense content extends. It is perfectly justified, when starting from the point of view of this everyday consciousness, not to separate the I from the sensory content, but to say to oneself: in that red, in that this or that sound, in that this or that sensation of warmth, of touch, in that this or that taste, smell, is present, then the ego is also present, and to the extent that these sensations are not present, the ego, as it is experienced in the ordinary waking state, is also not present.

I have often presented this as a finding of soul observation. I made it particularly clear in a lecture I gave at the Philosophers' Congress in Bologna in 1911, where I tried to show how what is experienced as the self should not be separated from the whole range of sensory experiences. We must therefore say: the I is essentially bound – I am always speaking of experience – to the sense perceptions. Right? We are not considering the I as a reality now; on the contrary, we want to point to the I as a reality in the course of these three lectures, today, tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. We now want to focus solely on what we call the I-experience in the realm of our lives.

You know how difficult it is to live in abstract ideas, in ideas that are not imbued with the content of sensory experiences. This goes so far that there are many philosophers who claim that such thinking, such imagining, that is free of sensuality, without any sensory perceptions being present at the same time, even if they are only sensory perceptions reflected from within, is not possible at all. But now, when we really observe our soul, it soon becomes clear that our inner experience is not exhausted by sensory perceptions, that we simply penetrate from sensory perceptions to what we call ideas. We only get the pure picture of the presentation when we look clearly at what arises from a complex of sense perceptions, which we have turned away from and which we still imagine afterwards, but now with the help of the same forces that otherwise serve us in remembering. Of course, it cannot be said that the content of the sense perceptions does not enter into these presentations. But the activity that can be observed in the human soul is different when we experience a sensory perception in connection with the outside world or when we merely imagine this sensory perception.

But this life of imagination leads us away to a great extent from what is actually the essence of our ego experience in sensory perception. We cannot say that we have a strong sense of self when we are merely imagining; on the contrary, when we are merely imagining, there is always the tendency for this sense of self to become obscured, which manifests itself in the transition to a dreamy state or even to a kind of drowsy state when we are merely imagining. We delve deeper into our inner being when we merely imagine than when we live in connection with the outer world through sense perception. In this regard, each individual must turn to self-observation. One can observe how there is a tendency to dampen the I when sense perception is dampened. We can then make progress if we link the experience of the senses to the idea of our I in our astral body.

So that we can say: just as life in sensory perception belongs together with the experience of the I, so the experience of the idea belongs together with the astral body. Above all, this damping of the ego is expressed – and this is actually the most significant thing to take into account if one wants to understand what I am actually explaining now – by the fact that, when we perceive with our senses, we have something quite individual. The complex of sensory perceptions that we are currently experiencing cannot be experienced exactly the same way by anyone else. It is something quite individual, and in this quite individual we have at the same time our I-experience. In so far as we ascend to the experience of thinking, we have at the same time the power to arrive at something more general, for example to form abstractions which can then be communicated in the same form to others, and which others can understand in the same way that we do. We ourselves can only understand the individual sensory perceptions that we have throughout our lives; but the images that we attach to them take on a form that is more general , that it can, as it were, be communicated to a larger number of people.

But this already testifies that the I attenuates as we move from sensory experience to imaginative experience. But at the same time we go deeper within ourselves; that is also an immediate experience. Now, as the images, or rather what takes place within us for their formation (which we will leave undetermined for today), as this continues to develop, the images become memories. Images actually initially disappear from our consciousness. From some unknown source – let us leave it undefined for today – facts arise, in the wake of which we can evoke the same ideas.

That is the only thing we can assert. If we stick to the facts, we cannot go along with those psychologists who say that the representations then go down into the subconscious, where they go for a walk without the consciousness knowing anything about it, and when one remembers, they come up again. That is not the fact of the matter. There is initially nothing to suggest that an idea that I formed three years ago continued to exist until today and went for a walk somewhere in the depths of the soul, only to come up again today when I remember it. Rather, the only thing that can be said, if one wants to speak precisely, is this: At that time I formed the ideas; those abilities that followed on from the formation of these ideas are capable, in their further development, of bringing these ideas consciously to the surface again today. That is the only fact. And if people were inclined to look at the facts everywhere, there would certainly be far fewer theories and hypotheses in the world than there are. For precisely with regard to what I am now explaining here, most people believe that what they have once formed as an idea lives somewhere in the indefinite and then comes walking back.

But we also know that the idea that one forms in connection with a sensory experience is precisely temporary, and that, even if this is sometimes concealed, an inner force must be developed that can be experienced when a past experience in the memory becomes an idea again. That which becomes the cause of a memory-image is seated deeper within us than the ordinary image linked to a sensory perception. It is a memory-image grounded in our organization. It is also connected with what we are as a temporal being. We know that images can be remembered in different ways, depending on how far back in time they lie. If we summarize all the facts that come into consideration, we have to say to ourselves: in any case, what has been experienced in a sensory perception has entered the stream of time in which we ourselves live. Certain sensations that we have while a memory emerges tell us how remembering is actually connected to our entire organization. We also know how, in the different stages of life, that is, in the succession of time in our life between birth and death, the power of remembering is greater or lesser.

If we follow all these facts, then we will be able to say that, just as the power of imagination lies in the astral body, the power of remembering lies in the etheric body. So that, if we summarize remembering in the word memory, we can say: Memory is as one with the etheric body as the life of imagination is with the astral body, as sense perception is with the I. In any case, what underlies the imagination is taken up in the course of time of our existence. Just as our growth and development between birth and death is contained in a certain stream of time, so what is experienced as memory, what is experienced as memory, is contained in this same stream and we feel the connection. Now, however, something is added to those things that I have discussed so far, and which can already be found by anyone with some subtle attention in faithful self-observation. That the I is connected with sense perception is a very obvious fact, and the one who does not admit it simply does not want to observe a very obvious fact. That the experience of imagination is connected with the astral body is something that can be discovered through ordinary observation. However, more subtle observation is required if one wants to examine the interconnection of the etheric body and memory. But even here one can still, I would say, manage scientifically, especially if one observes pathological cases, memory disorders and the like, and sees how they are connected with growth and nutritional disorders in particular. And we must consider the nutritional forces as lying in exactly the same direction as the growth forces or the reproductive forces. It is certainly possible to put together a series of observations that still show this connection between memory and the etheric body.

On the other hand, what I have to add now only arises from imaginative observation, and I would say that it can at best be sensed by ordinary observation. But when it has been found through imaginative observation, the whole context in which these things can be placed gives the healthy human mind complete assurance of the matter. We penetrate further and further into our own being, so to speak, starting from the outside and going inwards, if we start from sensory perception and the I, from mental experience and the astral body, from memory experience and the ether body, and then descend into the physical body.

In the physical body, we are indeed dealing with something that is still connected to memory, but not in the same way as the etheric body. To better understand what is present in imaginative observation and what I will characterize in a moment, we can take the result that is present in some pathological disturbances. The person then acquires certain inclinations, I might say tendencies, in their physical body; these do not have to go so far as to cause involuntary movements or spasms, but they could of course go so far as to cause death, but that actually belongs to a different field. When involuntary movements occur, I would like to say, of a more innocent kind, then the person who wants to deal with such things at all can already see that in a certain category of involuntary movements there are after-effects of experiences. If someone shows a tendency to do this or that habitually but involuntarily with his fingers, then one can always point out, if one has only enough examination records, how this or that complex of experiences leads precisely to these things. These must not be movements beyond a certain degree of involuntariness, but, I would say, semi-involuntary movements.

You see, it is the case that what has been experienced is too strongly imprinted in the physical body; it may still be imprinted in the etheric body, but not too strongly in the physical body. If it leaves too strong an impression on the physical body, then the physical body comes under the influence of the memory. It must not do so. Imagination shows us that what works in memory is still movement in the etheric body, is still, as it were, evolving movement in the etheric body. It accumulates in the physical body. It must not completely permeate the physical body; it must be repelled by the physical body.

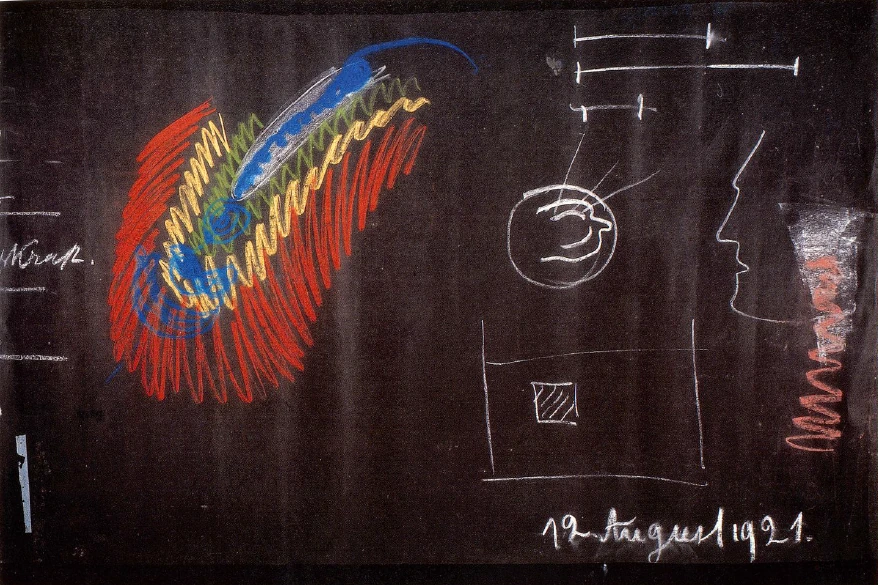

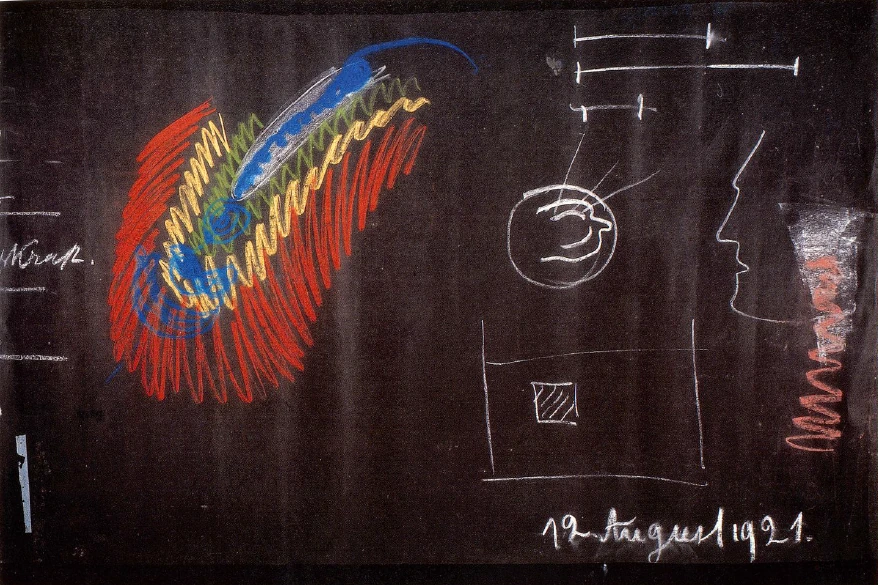

If I wanted to draw a diagram, it would be like this: Let us assume that we have the physical body here (see drawing, red), we have the etheric body here (orange), we have the astral body here (green), and finally we have the I here (white). Now a sensory experience takes place. This sensory experience is first taken up into the I. An idea is attached to it by becoming rooted in the astral body; the power takes effect, which then makes remembrance possible by becoming rooted as a movement in the etheric body. But now it has to be stored. It must not go further, it must not penetrate the physical body completely, but must be stored here. In the physical body, an image arises, of course at first quite unconsciously, of what lives in the memory. The image is not at all similar to what the experience was, it is a metamorphosis; but an image arises. So that it must be said: just as the memory is connected with the etheric body, so an actual inner image is connected with the physical body. We always have an impregnation, an image, in our physical body when such a movement originates in the etheric body; of course, this image can only be reached through imaginative visualization. There you can see how the physical body actually becomes the carrier of all these images. You may say: But I cannot possibly have the image of a church tower in my physical body! I will first give you an idea of how you can indeed have the image of a church tower in your physical body by picturing the matter for you.

Suppose, for my sake, you have a face in front of you, and you let this face be reflected in some mirror that completely distorts the face (it is drawn). Let us assume that something terrible arises within, something terrible. Now I do not mean that from the external experience, say of a church tower, something terrible arises as an impregnation in the physical body, but in any case, of course, something unlike it must arise. Now think, if you get such a monster here from this beautiful forehead, it is caused by the curvature of the mirror. If you can take into account the curvature of the mirror, then you can reconstruct the face from the caricature in connection with the curvature of the mirror, even if you do not have this face in front of you right now. So, if you understand the nature of the caricaturing mirror through which you receive the caricature, you can reconstruct the beautiful face. So there is no need for something similar to a steeple or a drama to be present inside the person, something that one has experienced or the like, but what arises in connection with the nature of the whole person naturally makes it possible to reconstruct the thing in reconstruct the matter in the same way.

So no objection can be made from the fact that, of course, because the world is large and shaped differently from the human interior, the image cannot be there in the human interior. The image is there, and in a sense the image is the last thing in the human being, where the external experience arrives. The other, imagining, remembering, are transitional moments. What we experience in the outer world must not simply pass through us. We must be an insulator; we must hold it back, and in the end our physical body does that. Our astral body changes it, makes it pale in our imagination; our etheric body takes away all content and contains only the possibility of evoking it again. But what is actually produced in us is pictorially impressed upon us. We live with it. But we must not let it pass through us. Suppose we were to let the image pass right through; it would not be reflected back by the etheric body in an elastic way, so to speak; it would pass through the etheric body, pass through the physical body, and we would always fidget around in the world as the events command us to. It is not easy to describe more complicated things, but if, for example, I saw a person moving from right to left, I would immediately want to dance from left to right, to imitate everything I see. I would want to imitate in myself, in my form, everything that I experience externally. It first arrives in the astral body, which already has a paralyzing effect, then in the resiliently reflecting ether body, then especially in the physical body, which accumulates the whole thing. In this, there is an isolation of what I perceive from the outside. And in this way, what I experience in the outside world works in me.

From knowing that a person consists of a physical body, an etheric body, an astral body and an ego, we know a scheme; but what matters is that we then fill in the concrete results into this scheme, in this case sense perception, imagination, memory and then the very concrete image. This is what gives content to these schematic concepts. And one must arrive at such content more and more if one wants to advance to an understanding of what is reality in the world. One cannot, for example, say: Yes, one divides the human being into physical body, etheric body, astral body and I, as if there were boundaries! If you are a reasonable person, you do not initially claim that there are other boundaries than those that arise when you take the formation of images, the experience of memory, the experience of imagination and the experience of sensory perception. But you have to have an open mind about the differences between these four types of experience.

That is one way of approaching these things. But now let us approach the subject of human beings and their behavior in the world from a different direction. Suppose we go for a walk. When we walk around – I have already touched on this here in another context – we cannot, in our external observation, distinguish between our walking and the movement of an inanimate object. Whether I observe a stone in its trajectory from the outside, merely in terms of movement, or whether I observe a person running – if both have the same speed, then the same fact is present in the external image. If I disregard everything else and look only at the body in motion, then in the case of both the stone and the person, I am dealing with a change of location. I observe this change of place, this speed. And this is ultimately what we are aware of when we move in everyday life; for we must distinguish between the intention to carry out a movement and the actual movement. When I think about a movement, I can remain completely calm. I can think myself into motion, and if I have some imagination, I can visualize myself moving. The idea that I then have when I really move is no different from the imaginative idea that I have when I am still and just think about moving.

So we have to distinguish very carefully between thinking about our movements and our real movements. But these real movements, we also imagine them only externally, no differently than we imagine motionless objects. We see how we thereby obtain different distances from these or those objects. We perceive our movements quite externally; that is added. And when we speak of movements – I do not want to go into the question of whether this is a hypothetical idea or a more or less well-founded idea, that is a matter for another chapter – but when we have movements, we also have force.

So, first of all, I will stick to the usual facts: where there is movement, there is naturally the development of a certain force. So we can say: The moving human being unfolds a certain force. We cannot speak of more than force, and we must also identify this force that it unfolds with some object, even an inorganic one. So let us consider only the physical body, either as a whole or in its individual parts; in that it moves, it moves like any other inanimate object. So, when we imagine ourselves moving and look at the physical body, we can only speak of force here.

The situation is different when we begin to look inside the being. We must be clear about one thing: while we are moving, inner processes are taking place in us. Substances are being consumed. Something is happening that is connected with the forces of growth, nutrition and reproduction. These are forces that we cannot address in the same way as we address the forces that we perceive in the external movement of an inanimate body. When we observe a plant in its growth, we must be clear about what is present when the plant grows larger and larger – and the same applies to the growth forces of animals and humans – that the unfolding of forces is different from that which underlies it when we have a merely externally observable moving body, be it the externally observable moving of one's own body or a human body in general. What is present when growth processes take place – and I also call growth processes in the broader sense those that take place when we are in motion, for example – what takes place there, we must look for in the etheric, in the etheric body. What we observe in the external movement, in the relationship of the person who is in external movement to this external world, does not cause us to look at the etheric body. At the moment when we observe what is happening internally, we must look at the etheric body. And if we define the concept of growth as broadly as I have just done, we can say that the specific growth force, which also includes nutrition, the use of materials, and so on, this specific force now urges us to move up to the etheric body. We see this growth force in the plant world.

To show you that these things are not merely contrived but can at the same time be corroborated by spiritual scientific observations, I would like to expressly say that what we see in the growing or generally internally changing organism , namely in the plant organism, where it appears purely, is entirely due to the fact that the power which otherwise expresses itself only in external movement comes into a certain relationship with what may truly be called ether. I would also like to convey this to you figuratively.

You are familiar with the often-mentioned fact that a solid body in a liquid loses as much of its weight, receives a lift, as the weight of the displaced water body. Now, the forces that underlie the external movements of physical bodies are, in a sense, rigid. They have an inner rigidity, just as a solid body has a certain weight. When you put a solid object into water, it loses some of its weight. When you combine the forces that normally cause external movement with the forces of the ether, they lose their rigidity; they become internally mobile. Thus a force, which as the moving force of the inorganic is so great and cannot become greater if it is only an external moving force, loses its rigidity when it combines with the ether, it can expand or contract. And as such a force it is then active in growth, and in all internal processes.

This Archimedean principle can be expressed as follows: Every solid body loses in a liquid as much of its weight as is the weight of the displaced liquid body. Every force, so one can continue to say, loses, when it combines with the ether forces, of its rigidity, as much as the ether forces are of their suction forces, as the ether forces bring to it in suction forces. It becomes movement, and with that it becomes what it becomes active as, say, in the plant organism, but also remains active in the animal organism and in the human organism. If we now go further up from the etheric body to the astral body, thus in the outer view from the plant to the animal, what was initially an inwardly mobile force in the growth force is now free – as I have already described in the case of the forces that are released in the seventh year with the change of teeth – inwardly free, so that what is taking place is no longer bound to the forces of the physical body. What expresses itself as free forces are the instinctive forces in animals and in humans. So we penetrate up to the astral body and what is still force below is given to us as instinct. And if we penetrate up to the I, instinct becomes will.

I: sense perceptions will

Astral body: life of imagination instinct

Ether body: memory growth forces

Physical body: picture energy

This relationship of the will to the instincts, which arises in an unbiased observation of ordinary mental life, is in turn suitable for a rational self-examination. From another side, we have filled what is here only a mere scheme with the content of experience.

We can say that when we look at the physical body, from the inside it presents itself to us as that which continually accumulates experiences and images; when viewed from the outside, it is an organization of forces. And it is also correctly observed in the physical body that it actually consists of an interaction of forces with images. If you imagine a painted picture, you would have to imagine it spatially, in such a way that it is not a rigid picture, but an inwardly moving picture, with forces at work at every point. Then you get something of what must be imagined in reality under the physical body.

If you imagine the growth forces from the inside and think of them as imbued on the other side of what underlies memory – but now not as mutually concealing ideas, but precisely as what underlies memory – so ether movements on the one hand, which swell up, accumulate through the inner processing of the absorbed nutrients, which accumulate through the movements of the human being, in conflict with what sinks down from all that has been perceived by the senses and imagination and then vibrates downwards in the ether body to preserve the memory, if you imagine this interaction of above and below, that is, of what vibrates downwards from the imagination and what comes up from below, from the process of nutrition, growth and eating, both interacting: then you get a vivid picture of the ether body. And again, if you think about everything you experience yourself when instincts are at work, where you can clearly understand how blood circulation, breathing, how the whole rhythmic system works works in the instincts, and how these instincts depend on our upbringing, on what we have absorbed: then you have the living interplay of the astral body. And if you finally imagine an interplay between the acts of will, there is kindled everything that you want with what the sense perceptions are, so you have a living picture of what lives into consciousness as the I.

But this is only a rough scheme. We have only had a very small sample of experiences, and they have to be fitted into a scheme. You first have to have the cupboard before you can put the objects in it. Not so, the ordinary psychologist or physiologist, who first observes these things. And if someone happens to have all kinds of linen and clothes but no cupboard, and just piles them up, well, then it will turn into chaos in the course of time! That is our present-day psychology and physiology. You really need a closet. Just as the person who makes the closet should know in a certain way how the closet needs to be organized so that you can really get in what you want to put in, so now what is being organized must what is being organized must still be inexplicit in a certain way, even though it can only be abstract – just as a cupboard is abstract when it is still empty, but not when it is full. If there is an empty cupboard somewhere, it is also inexplicable.

So you see, there are of course an awful lot of points of attack on anthroposophy, depending on where you start. But one can also, and I have tried this in my “Theosophy”, already let it be known that while one is obliged to set up the cabinet first, something concrete is already pressing to do so. But then one must have the patience to ascend to that which brings abundance into the scheme. And this is what must always be said to anthroposophists in particular: one should not create the impression in the world that everything has already been said when such abstract terms as physical body, ether body, astral body and I are used. If one merely says: 'The human being consists of a physical body, ether body, astral body and I', then one has said nothing at all except four words. For there is, of course, a great difference between saying this out of the fullness of knowledge, as a structure that can be used as a guide to build upon, and dogmatizing it and communicating it as dogmas.

That is why it makes such a repulsive impression when it is simply handed down: The human being consists of a physical body, an etheric body, an astral body and an ego. It all depends on how you say such things. You don't have to go as far as was once said in an anthroposophical lecture: “For the sake of simplicity, we divide the human being into seven parts.” The nonsense is already great if you believe that you can capture something real just by putting it into some kind of scheme. It is there to provide guidelines within which observations can be made.

After I have shown you how certain viable concepts, such as will, memory and so on, can be incorporated into the anthroposophical conceptual scheme, we will move on to a further consideration of the human being tomorrow.

Source: The Rudolf Steiner Archive

No comments:

Post a Comment