I am come to send fire on the Earth;

and what will I, if it be already kindled?

But I have a baptism to be baptized with;

and how am I straitened till it be accomplished!

—Luke 12:49-50

"Behold, I make all things new." — Revelation 21:5

Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland

First-Class Lesson #19 of 19

August 2, 1924

My dear friends! Once again, we will begin by allowing the verse to flood into our souls, the verse that can presently bring to us how all that is and is becoming in the world, what has been in times long past, is in the present, and will be in the future, how out of all sounds forth to us, evermore resounds in us, and calls out to us to seek self-awareness, and as such is the foundation for true, for truly balanced world-awareness.

O Man, know yourself!

So sounds the word of worlds.You hear it soul-forcefully,

You feel it spirit-powerfully.Who speaks so world-mightily?

Who speaks so heart-inwardly?Does it work streaming through space

Into your sense’s self-experiencing?Does it sound weaving through time

Into your life's evolving stream?Are you the one, who yourself

In sensing space, in experiencing time

Creates the word, feeling yourself

Estranged in space’s soul-emptiness,

As you lose the power of thinking

In time’s destroying stream?

Well, my dear brothers and sisters, we have allowed mantric verses to pass by our souls, which in their craft comprise the way forth into spirit-land, past the Guardian of the Threshold, into what is at first the dim, dark, night-bedecked spiritual world, which at first just feels light, then for soul-perception becomes light. In this spiritual world we have seen how a person partakes, generally unawares although he can become aware, how a person partakes of the dialogue of the higher hierarchies among themselves, which the hierarchies among themselves work on and interweave into the world, which itself is spoken forth in word-of-worlds. And finally, we have been able to situate ourselves in that world-domain in which the various hierarchy choirs ring all together. Let us bring to mind once more how the choirs of the various hierarchies resound within one another, there, where we are infused with what the high beings of the Second Hierarchy are saying, where we are infused with what the beings of the First Hierarchy are speaking forth. As they speak, we presently begin to hear them resounding together as a choir.

The Guardian makes us mindful, as we have already become acquainted with in previous lessons, of the following:

See the ethereal iris’s

Light-abundant round.

Through your eyes’

Light-forming force

Let your “I” penetrate through the arc,

And then behold from yonder watch

Color flooding the world’s chalice.

After the Guardian of the Threshold has advised us about the spirited mystery of the rainbow, the Angels, Archangels, and Archai peal forth as if from a choir:

Sense our thoughts

Color breathing living

In the chalice's flood of light;

We carry the sensory-semblance

Into spirit-being-realms

And turn ourselves world-infused

To the service of higher spirits.

The spirits of the third hierarchy clarify how in service to humanity they apply in supplication to the Second Hierarchy, to the Exusiai, Dynamis, and Kyriotetes. Out of their domain we hear, once again in chorus:

What you have taken up,

Enlivened from dead sensory-semblance

We wake it in existence;

We add it to the rays of light,

So that the emptiness of matter

Will bear spirit nature

And manifest endowed with love.

And when we have heard how the spiritual beings of the Second Hierarchy align with our “I-am” in world-creativity, then the Thrones, Seraphim, and Cherubim of the First Hierarchy peal forth in choir:

In your worlds of will

Feel our world-wide impact;

Spirit shines in matter,

When we are thinking working;

Spirit works in matter,

When we are willing living;

World is I-willing spirit-word.

And now we stand within the spirit word, within the spirit word that lies at the foundation of world formation. We feel this spirit word around about us. We feel the world infused throughout with this spirit word. We feel ourselves interwoven with this spirit word. We feel the influx of this spirit word into our most intimate human nature. And finally, we feel this world-wide spirit word streaming into our hearts. We feel ourselves there with the whole of our human nature in the surging of this spirit word. We feel ourselves there in spirit in the word-interlaced world spirit.

There is the Guardian in the distance. We have walked past the Guardian. Presently he is quite distant. We hear him yet softly, as he now allows a final admonishing word to stream forth to us from his distant reach.

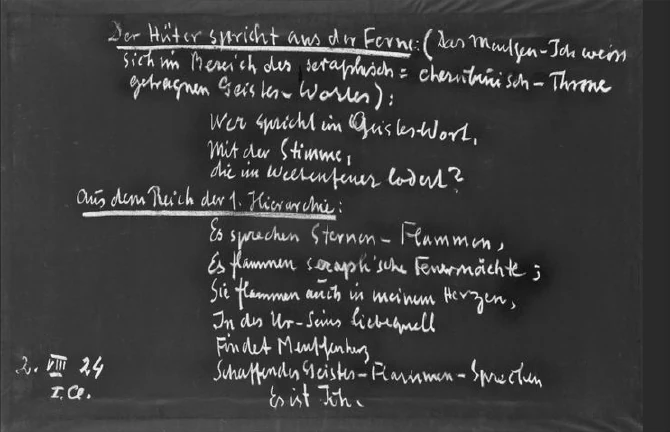

The Guardian speaks from afar. The human I knows itself in the realm of the Seraph-Cherub-Throne borne Spirit-Word. The Guardian speaks:

Who speaks in spirit-word

With voice

That blazes in world-fire?

There sounds forth in answer from the realm of the First Hierarchy:

Speaking is star-flaming,

Flaming are Seraphic fire-powers;

They flame also

– we feel the world-speech, the language of the world-word within ourselves –

in my heart.

In the primal source of love1

The human heart finds

Creative spirit-flaming-speech:

It is I.

My dear brothers and sisters! Whoever would penetrate into the esoteric realm should certainly feel at once the primeval sacred ehyeh asher ehyeh,2 the I am which is a sacred holy word, that resounds here but emerges from a reality on the other side. The I am that we take hold of in fleeting thoughts is merely a reflection.

We must most certainly make ourselves aware that the true I am does not emerge from us in speech within the earthly realm, initially. If we are worthy and would say the I am, we first must come into the realm of the Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones, for there the I am rings true. Here in the earthly realm, it is somewhat illusory.

But there, in yonder watch, in order to experience truly and inwardly the I am, there we must hear world-words. We must solemnly hear the question of the Guardian of the Threshold, who most certainly speaks there in world-words. With thunderous flaming — spiritually thunderous flaming — the Seraphim, who forge their way through the world, there where we now stand the Seraphim speak the world-word’s fiery speech. The word is flame, flaming voice. And as we experience ourselves in this blazing world fire, in this fiery speech speaking in flaming voice, then we experience the true I am.

That is contained in these words, which come now as a question from the distant Guardian of the Threshold, whom we have long ago passed by, and then in answer comes forth from the domain of the First Hierarchy:

Who speaks in spirit-word

With voice

That blazes in world-fire?Speaking is star-flaming,

Flaming are Seraphic fire-powers;

They flame also in my heart.

In the primal source of love

The human heart finds

Creative spirit-flaming-speech:

It is I.

[The first part of the mantra was now written on the board.]

The Guardian speaks from afar (The human-I knows itself in the realm of the Seraph-Cherub-Throne borne Spirit-Word.):

Who speaks in spirit-word

With voice

That blazes in world fire?From the realm of the first hierarchy:

Speaking is star-flaming,

Flaming are Seraphic fire-powers;

They flame also in my heart.

In the primal source of love

The human heart finds

Creative spirit-flaming-speech:

It is I.

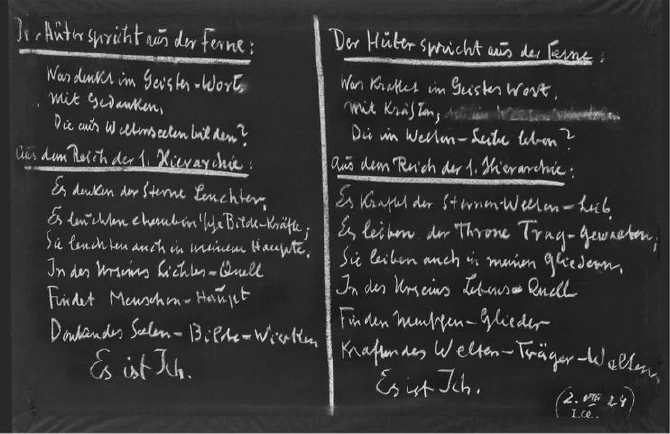

When a person’s customary word resounds, then what speaks by means of the person’s word is human thinking. And when the spiritual world-word resounds, then what speaks by means of spiritual world-word is world-thinking. This lies embedded within the following question of the Guardian, that he now sets forth as a second from the distance.

The Guardian speaks from afar. The human-I knows itself in the realm of the Seraph-Cherub-Throne borne Spirit-Word:

What thinks in spirit-word

With thoughts

That form out of world-souls?

These are the very thoughts issuing, coming forth, of world-souls, from all world-souls, from all the beings belonging to the various hierarchies. They sculpt, form, fashion everything that exists in the world’s realms. Therefore, the Guardian asks who it is that thinks the potent thoughts that form and fashion all things:

What thinks in spirit-word

With thoughts

That form out of world-souls?

Again, coming to us from the realm of the First Hierarchy:

Thinking are stars luminaries,

First it was the flaming speaking the words. The stars flaming speak the words. The luminaries, from which the flaming comes, think.

Thinking are stars luminaries,

Illuminating are cherubic form-forces.

They illuminate also in my head.

—So says the person to himself, standing within it all.—

In the primal source of light3

The human head finds

Thoughtful soul-forming work:

It is I.

That is the second colloquy, the second call, as if the beings of the First Hierarchy were giving us world-permission, that we within ourselves may experience the "I am".

What thinks in spirit-word

With thoughts

That form out of world-souls?Thinking are stars luminaries,

Illuminating are cherubic form-forces.

They illuminate also in my head.

In the primal source of light

The human head finds

Thoughtful soul-forming work:

It is I.

[The second part of the mantra was now written on the board.]

The Guardian speaks from afar:

What thinks in spirit-word

With thoughts

That form out of world-souls?From the realm of the first hierarchy:

Thinking are stars luminaries,

Illuminating are cherubic form-forces.

They illuminate also in my head.

In the primal source of light

The human head finds

Thoughtful soul-forming work:

It is I.

The world-spirit-word must speak. From it, thoughts stream forth. But the thoughts are formative, the thoughts are infused with force; the thoughts stream forth and world beings and world events thereby come into being, becoming all that is. In it the word-formed world-thoughts live, the thought-laden world-words. It is not a simple sort of thinking; it is not a simple sort of speaking; it is formation, creative forceful crafting, forces streaming forth in words. Forces imprint the thoughts out into world-beings, into world-events.

All this is indicated, pointed to, in the third question which the Guardian of the Threshold puts to us from afar:

What crafts4 in spirit-word

With crafting strengths5

That live in the body of worlds?

The whole world, which there resounds with the world-word, which there is thoroughly illuminated with world-thinking, is just the same as what thinks and speaks in human beings, is incorporated or embodied, is just the same as what resounds in the world-word. What shines thoroughly illuminated by thinking is world-embodiment. The Thrones carry it, bear it, or said somewhat better, it is that within which the Thrones bear the thoroughly thought-illuminated, world-spirit-word.

To this the answer comes, from the realm of the First Hierarchy, to the question of the Guardian:

Crafting is star-world-embodiment,6

Embodying7 are thronal bearing-powers;

We must build a word that is rather uncommon. But just as one illuminates by light and as the verb to live is built from the noun life, likewise in what emerges as a force in what is borne by the body, likewise one can build the word abide, or embody. Then to embody is nothing that is dead, to embody is nothing that is finished, to embody is something that is active at all times, is versatile, is moving, it embodies.

Embodying are thronal bearing-powers;

They embody also in my limbs.

In the primal source of life8

The human limbs find

Crafting world-bearer-power.

It is I.

World-word, world-thinking, then world-embodiment. Speaking, then thinking, and in the third question the Guardian refers to world-embodiment:

What crafts in spirit-word

With crafting strengths

That live in the body of worlds?Crafting is star-world-embodiment,

Embodying are thronal bearing-powers;

They embody also in my limbs.

In the primal source of life

The human limbs find

Crafting world-bearer-power.

It is I.

[The third part of the mantra was now written on the board.]

The Guardian speaks from afar: (The human-I knows itself in the realm of the Seraph-Cherub-Throne borne Spirit-Word.)

What crafts in spirit-word

With crafting strengths

That live in the body of worlds?From the realm of the first hierarchy:

Crafting is star-world-embodiment,

Embodying are thronal bearing-powers;

They embody also in my limbs.

In the primal source of life

The human limbs find

Crafting world-bearer-power.

It is I.

In a certain way, my dear brothers and sisters, it is a sort of closure along the path, the path that began in the realm of illusion, in the realm of maya, that has led us to the Guardian of the Threshold, that has led us in self-awareness through to self-awareness in the spiritual realm, and that has allowed us to hear the choirs of the Hierarchies. In a certain way it is a closure, for we now stand in the position of being allowed to experience in ourselves the true I am, the ehyeh asher ehyeh.

We are able to experience it in this dialogue, as the threefold It is I springs us forth from the heart, allows us to spring forth from the heart, so that when it springs us forth from the heart, it will allow into our heart the echo of what the Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones allow to resound within this heart.

Who speaks in spirit-word

With voice

That blazes in world-fire?

Speaking is star-flaming,

Flaming are Seraphic fire-powers;

They flame also in my heart.

In the primal source of love

The human heart finds

Creative spirit-flaming-speech:

It is I.What thinks in spirit-word

With thoughts

That form out of world-souls?

Thinking are stars luminaries,

Illuminating are cherubic form-forces.

They illuminate also in my head.

In the primal source of light

The human head finds

Thoughtful soul-forming work:

It is I.What crafts in spirit-word

With crafting strengths

That live in the body of worlds?

Crafting is star-world-embodiment,

Embodying are thronal bearing-powers;

They embody also in my limbs.

In the primal source of life

The human limbs find

Crafting world-bearer-power.

It is I.

With that, my dear brothers and sisters, the first stage of the school’s First Class has in a certain sense been completed.

We have allowed those impartations that we could receive from the spiritual world — for this school is a school constituted by the spiritual world itself — we have allowed those images and inspirations that can come from the spiritual world to be drawn into us. They constitute what for our souls is the way to go forth in capturing the true human "I" in the vicinity of the Seraphim, the Cherubim, and the Thrones.

My dear brothers and sisters, as you have heard in general anthroposophical proceedings concerning the supersensory School of Michael, it had initially resounded inwardly in such heart-felt lessons. The mighty images, cultivated imaginatively at the start of the nineteenth century, and then placed before the soul, if one was so destined to be in the vicinity of Michael, the revelations of the school of the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, which in the supersensory world was led by Michael himself and high spiritual beings, in the aforementioned sense. And now we stand before this anthroposophical school founded by Michael. We feel ourselves within it. Michael-words they are, Michael-words that ought to characterize the way that leads forth into the spiritual world and into the human "I". These Michael-words of the esoteric Michael-school have built, so to say, the first stage.

As will then be announced, when we meet once again in September for these Class lessons, then it will be the will of the Michael-power to begin by highlighting the imaginative cultus-revelations from the beginning of the nineteenth century. That will be the second stage. All that has now been brought before our souls as mantric words will stand before our souls more fully in imagery which, insofar as is possible, will be the imagery as brought down here of the supersensory imaginative cultus from the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The third chapter of this school will build what will lead us on to those interpretations that were given to the mantric words in the supersensory Michael School of the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries.

We should feel that we place ourselves in the midst of all that is within the spiritual world itself. Ever and again, however, we should look back upon the physical-sensory world, and in exemplary-unassuming fashion accommodate ourselves to that which has dominion in the sensory-physical earthly world. To this end, and in closing, let us once more allow to sound before our souls all, if we are capable of receiving it, if we are able to sense it, all that sounds forth from every stone, from every plant, from every animal, from every billowing cloud, from every bubbling spring, from every rushing gust of wind, from the woods and mountains, and everywhere from the things and events of the earth all around, if we can sense it there as it sounds forth.

We were in the realm of the Seraphim, the Cherubim, and the Thrones. By itself the voice of the Guardian sounded forth from afar. We go in modesty back again, past the Guardian, back into the realm of the sensory show, into what is apparent to the senses. And again, we allow the words to reverberate within us:

O Man, know yourself!

So sounds the word of worlds.You hear it soul-forcefully,

You feel it spirit-powerfully.Who speaks so world-mightily?

Who speaks so heart-inwardly?Does it work streaming through space

Into your sense’s self-experiencing?Does it sound weaving through time

Into your life's evolving stream?Are you the one, who yourself

In sensing space, in experiencing time

Creates the word, feeling yourself

Estranged in space’s soul-emptiness,

As you lose the power of thinking

In time’s destroying stream?

Der Hüter spricht aus der Ferne: Das Menschen-Ich weiß sich Der Hüter spricht aus der Ferne: Das Menschen-Ich weiß sich Der Hüter spricht aus der Ferne: Das Menschen-Ich weiß sich | The Guardian speaks from afar: The human-I knows itself The Guardian speaks from afar: The human-I knows itself The Guardian speaks from afar: The human-I knows itself |

Source: August 2, 1924

Jñāna Yoga — Anthroposophy — culminates in Hatha Yoga

Hatha Yoga: The union of the Sun (Ha) and the Moon (Tha)

The concluding lessons of the First Class:

Lesson 16:The chela becomes Anthropos-Sophia

Lesson 17: [Manas] The Bride of Christ: The microcosmic Anthropos-Sophia becomes the macrocosmic Moon Sophia

Lesson 18: [Buddhi] Ha-Tha Yoga: The union of Sophia and Christ the Sun God

Lesson 19: [Atman] Advaita (Nonduality): Not I, but Christ in me

Related post: Sophia

.jpg)