|

Ex Deo Nascimur [In Christo Morimur] Per Spiritum Sanctum Reviviscimus |

Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland

August 20, 1921

My aim yesterday was to show how the state of mind or consciousness of humanity has changed over the course of historical and prehistoric times, and I wanted to show this for the reason that it might make it easier to recognize the necessity of rising to a different state of mind in order to gain real, essential knowledge. And that is to a state of mind that differs from the one in which one has become accustomed to, which one cultivates in everyday and scientific life today and which one recognizes as something absolute that has existed as long as there have been people and that will exist as long as one will have the right to speak of people walking on earth. If we see how the soul has taken on a different inner constitution throughout the course of human development, then it will be easier for us to acknowledge a transformation of the present soul condition as well.

In order to tie in with what I said yesterday, I would now like to repeat in a few words, summarizing what can be derived from the last observations. I said that humanity, insofar as it can be regarded as civilized humanity, has actually only come to the present state of mind since the 15th century, and this state of mind is characterized, on the one hand, inwardly by the fact that we strive for an intellectual interpretation of the world, that we make use of our intellect to comprehend that which we call the world.

This intellectualistic orientation towards the world now also corresponds to a very specific area of the world, which can be grasped and understood through it. It is the world of mineral events and mineral forms, the world that has not yet risen to life. Today, it is often believed that even within purely intellectual endeavor, life may perhaps be grasped; but this only happens because one does not recognize the belonging together of the intellect in the inner and the inanimate in the outer world. If we go back beyond the 15th century and enter the period that, calculated backwards, lasts from the 15th century to the 8th century BC, we find a different arrangement of the human soul. And this arrangement is most characteristically encountered in the Greek mind.

There we are not dealing with an intellectual soul condition; concepts are not yet separated from words in the strict sense of the word. The Greeks essentially arrived at the workings of their soul not by inwardly visualizing concepts with a certain abstraction, as we do, but rather they heard, as it were, the sound of the words, even if it was not outwardly audible. What for us lives in the abstractness of concepts was tinged for him, if I may use the paradox, by the spiritually grasped sound, through the soundlessly, purely internally experienced sound. Just as we live in abstract concepts, so the Greek lived in the externally soundless sound. But this enabled him to perceive the living world as an external world. And so we see that wherever the Greeks wanted to form, let us say, ideas about the universe, about the cosmos, based on their presuppositions, they did not use the ideas taken from geology, physics, and chemistry that we use today, but rather what had settled in their souls through the growth, development, prosperity, , arising, passing away of that which lives vegetably.

If we go back even further, we come, however, to times that we can no longer count as historical in the strict sense of the word, then we come to the 8th century BC, to a period roughly up to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. And if we look around at the peoples who could be considered civilized at the time, we find that the essential of the soul's life was no longer sought in the inwardly experienced words, but in the imaginative shaping of the word structure, the language structure. Rhythm and thematic – that is, what lines up tone by tone, what penetrates into the world of sound and also into the world of noise, so that we only make it alive in our soul when we rise to the poetic shaping of language – that was the actual element of life of the, if I may use the word, educated peoples of that time. And they found satisfaction not by expressing some external thing or event through words, as the Greeks did, but by inwardly feeling, as it were, that which they believed to live everywhere in the world as rhythm, as harmony.

Thus, inner rhythm and inner harmony were what characterized the state of soul during that period. And if we ask ourselves what realm could be penetrated externally by such an inner state of soul, we find that it is the realm of that world of beings which can experience in itself intuitive perception. Thus, what is the animal world, what is the sentient world, what lives in the perception of the objective, that inwardly came to life for the people of that ancient time in the state of soul of which I have spoken.

And if we go back to even older times, you can guess that in a certain respect there must have been an awareness of the human being himself. In our own age we have a recognition of dead nature; this was preceded by a recognition of living nature. And if we go back further in time, we come to those times of which, from certain quarters, only the outlines can be discerned today, namely, the world-views that emerged from more or less enlightened Catholicism. Those very thinkers who have settled into, not the decadent state of Catholicism, but what in older times was Catholic philosophy, speak of an original revelation of mankind. One must indeed see many things in their proper light if one wants to judge these things appropriately. The Catholic Church has become something different from what she was, for example, in the times of the Catholic Church Fathers.

One need only look at Origen and one will find that Origen is already trying to bring everything that has been gained in philosophical depth in his time into Christian thinking. And so we also find among the older Church Fathers a clear awareness that there was once a primordial revelation to humanity. And those Catholic writers who have retained the better forces of Catholicism still speak today of the primordial revelations, which only later disappeared into paganism, which was increasingly heading towards decadence, so that the knowledge was lost. So that in these primal revelations of an instinctive humanity, that which was later brought by Christianity in its developed form was shown.

It is interesting when writers such as Otto Willmann talk about the primal revelation, when they going back to the mysteries and beyond the mysteries and pointing to such a primal revelation, by which people in those times in the 3rd and beyond the 3rd millennium of the pre-Christian era were inspired, if such a primal revelation is sought. It is not necessary for us to get involved in a more precise description of what is said about the primal revelation. But let us characterize in a spiritual-scientific sense what can be found when we go back to these prehistoric times of human civilization, where, through an instinctive state of mind, I will call it for the moment, not only the sentient but the human itself can be explored, that is, that which lives in man above the animalistic, the actual, the specifically human. Indeed, there was a time when the corresponding knowledge was instinctive, not even something that would be accepted today as knowledge, but a kind of direct experience, a dimly dreamlike experience, but one that contained something of the essence of the human being, so that one could objectify what the human being actually is as if through an inner living into this human essence. This epoch cannot be considered historically, although historical remains from it have certainly remained. How one has to look at these historical remains will become clear from what I would now like to give as a characteristic of this epoch itself.

When we speak of the state of mind that we now have as the humanity, the intellectualist soul, we are speaking of something that lies within the soul for ordinary experience, for ordinary experience, as we call the soul more or less clear or more or less trivial today. Even if we look at it in that epoch, for which Greek observation is typical, we are speaking of an inner experience of the word, and thus again of something that is within the soul. And even if we go back to the 9th or 10th century BC, to the 2nd millennium, to the end times of the 3rd millennium, we are still speaking of something that takes place in the soul, although it must be admitted must be admitted by anyone who knows these things precisely from their own observation that at the moment when the soul experience emerges from the word and enters into this rhythmic experience, into this experience of harmonies and, I would like to say, musically imaginative themes, then what is experienced in the soul always resonates quietly with the physical. Just as it can be felt that every time a person has a vivid dream, something happens in their physical being that leads to the constitution of dreaming, so the person of the characterized period knew that when he brought to life within himself something harmonious, rhythmic, thematic, it was as if the secrets of the world were revealed or unveiled to him, and something of the physical moved along with it. When we speak of our abstract, intellectualistic conception of the world, we have no physical resonance in our consciousness. We can devise theories about what might happen in the human nervous system when logical-intellectualistic thinking takes place. But such theories are only thoughts; they are not alive, they are not experienced.

In the same way, we still have to speak of the Greek soul when we realize how the word lived in this soul. But as I said, we already move beyond the purely soul realm to a slight involvement of the body when we ascend to the previous period. And we move even more from what we call the soul realm today into the realm of the body when we ascend to the ancient instinctive knowledge that existed in the earlier centuries of the third millennium BC and even earlier. There was a direct soul experience with the character of a physical experience. In those older times, one actually experienced a process that we today describe as physical – I do not want to discuss now whether with complete justification or with partial injustice – a physically described process where later experienced as soul-life, as we call it.

I would like to point out that when one comes from such experiences of humanity, which are so different from our own, one also has a difficult time using words. The things themselves become different, very unlike what one experiences today. Our languages have been formed for our present-day experiences, and one must try to use the languages in such a way that one can return to something that is no longer directly present experience today, and which can therefore only be touched upon weakly with the word usages that we have today. Therefore, I have to say that what we today call the soul did not really live in the inner soul state of these old people. Something actually lived in them that we today would describe as physical, even as bodily, in the same way as thinking or inward hearing of the word lives in a person today. So this old man experienced inhaling, holding his breath and exhaling not as we do, who have outgrown our involvement in the breathing process. He experienced this breathing as we only experience it in abnormal states, for example when we go through states of fear in our dreams and then wake up and notice that our breathing is disturbed. In this pathological state, we notice something of the interaction of the breathing process with the occurrence of images in front of our consciousness. We have outgrown the images that arise before consciousness when the normal breathing process takes place, because we have grown up to perceive the rhythmic in language, the harmonious in language, the thematic in language, to the inner coloring of the word, because we have grown up completely in our time to abstract conception, to the intellectualistic conception of the world.

But these three periods were preceded by another one, when man still, if I may use the expression, lived down in what we today call his physical body, and lived with his process of knowledge, which was inhaling, holding his breath, and exhaling. And what did man experience with inhaling? Today, this can only be taught by the imaginative knowledge of which I spoke in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds” and in my “Occult Science in Outline”. For what was experienced in that ancient epoch when inhaling was essentially an imagination; man's own imagination, the imagination of man as a figure was experienced when inhaling. Man felt this in breathing in – of course he had to focus his attention on it, in everyday life he did not always focus his attention on it – but he could, as it were, stop his everyday soul life and then he could experience it. He experienced it especially in moments when everyday consciousness was somewhat subdued. That was necessary for this. We would say today that he experienced the figure of the human being when he drew in his breath and approached the state of falling asleep or waking up; when he held his breath, he experienced the merging of this figure with the inner soul. He had the opportunity to experience the human form in the inhalation, the mistiness of this form in the retention of breath, and the connection of this auric mistiness of the form with the soul. Then, in exhaling, he experienced the soul's surrender to the outer world, the harmony of man with the outer world.

I said explicitly that the person could experience this in special moments. He could, as it were, focus his attention on the breathing process and then perceive such. He really did attain an instinctive knowledge - if you want to call it knowledge - by observing his breathing process, especially when he steered this breathing process inwardly, which resulted from practice. It was, so to speak, a descent into the physical body, through which the human being could be brought to knowledge.

Of course, we must not imagine that in those ancient times man spent the whole day from morning till evening only becoming acquainted with himself. I therefore said: when he directed his attention to it. But this attention could easily be drawn from the whole constitution of the human being.

Now, I said that this goes back to ancient times; but what has been preserved historically from those times is the method of knowledge, the breathing method, the yogic breathing, which is practiced in certain schools in India. This has been transmitted to a later time by the fact that it was elementary and natural in an earlier time. For a later time, certain preparations and certain manipulations of the breathing process were necessary. In earlier times, these manipulations arose as something that man learned in the course of his life, just as one learns to speak today.

What is called yogic breathing is an inheritance from an earlier time, when the whole soul constitution was different than it was later, and when man faced the world in an instinctive way through this different soul constitution. For it was, of course, very instinctive to grasp the essence, the secret of things, through breathing, not through thinking and inner speech, but through breathing. Where today we ponder intellectually in order to assemble individual facts into overall phenomena and to find natural laws through the calculating mind, and so on, there one inhaled that which, as the essence of the human being himself, should arise as instinctive knowledge within human nature.

It is of great importance to realize that not every human epoch corresponds in the same way to every other. Just as the constitution of the soul of people has changed, so too has the bodily constitution, albeit in a more subtle way. And it must be said that those who today believe that they can reawaken, for example, the process of breathing by penetrating the secrets of the world, as this breathing process was carried out in ancient times and as it has been preserved in natures who are, after all, constituted differently from modern European natures, are on the wrong track. It is absolutely necessary that, in addition to following the external history of the development of humanity, which has become a matter for the nineteenth century in particular, we now familiarize ourselves with an inner pursuit of what has taken place as a development of the soul parallel to this external physical development. One does more justice to the portrayal of external physical development if one is able to see the spiritual-soul development on the other side.

Those for whom these four types of human soul condition are now fully objective will be able to sense how the soul is viewed in a special way. First we have a state of soul that is actually no longer a state of soul at all, but a bodily state that lives in the breathing process; then there is the state that lives in the rhythmic-harmonic, in the imaginative-thematic process; then there is the state of the silent experience of the word, and finally that which lives in the intellectual process; and when one has all this in objective form, then one sees the soul in such a way that one must ascribe to it the most diverse possibilities for relating to the world. And it is necessary for the present time to know that there are such different possibilities, let us say, such different types of consciousness, and that for each state of consciousness other levels of cosmic life and cosmic existence come to light.

Today, it is often believed that there is only one state of consciousness, which one then tries to describe as something that can only be taken absolutely alone. But by wanting to limit oneself to this one state of consciousness, one simultaneously limits oneself to a single level of cosmic existence and cosmic experience. And we can truly say of today's state of consciousness that it is far removed from the realization of the actual human being. It clings to constructing a human being out of physiology and biology. For what we call psychology today is basically a collection of hackneyed words for something for which there is no real soul content left.

Humanity must first move forward again to grasp the living alongside the dead, the sentient alongside the living, the human alongside mere sentient cognition. As I said, I have made these remarks to facilitate an idea that leads to what is necessary today if we want to approach the human again, if we want to get to know the human again. For this human does not reveal itself to the state of consciousness that is primarily attuned to the dead, to the mineral.

We speak of the I, we think we can speak of the I. The fact that we have a word for this I is no proof that we also have a soul content with this word. There are philosophers today who understand the I only as a summary of what is experienced as an idea, as a feeling. In a sense, only that which is drawn from one idea to another, from one feeling to another, from one feeling to the idea as connecting lines, that which is itself quite abstract, is often understood today as the ego. But one can say that in a sense, even this understanding has a limited justification. For what is experienced in the soul when one speaks of such consciousness of the self is basically not even content.

You see, we can have a white surface, we can speak of white - I have used the image several times before -, we see the white, but we also see the black here in the middle. There is no white there, the white is missing, and yet we see the black through the white (it is drawn).

Those who are really able to analyse the soul can see that today we experience something in the soul that can be compared to this white. We experience pain and pleasure, we experience this and that sensation, love, hate, and so on. We experience perceptions, although these are already something rather gray for ordinary consciousness when they want to be relived in reflection; but we experience the I with this consciousness in the same way as the black in the white here. Where we experience nothing, where we experience a kind of hole in our consciousness, that is where we place the ego for ordinary consciousness. No wonder we speak of the ego; we are also speaking here of the black hole. What a person experiences from waking up to falling asleep does not include the ego. The question may arise before us: How do we even come to a possibility of gaining ideas for the ego? Yes, here the person who is seriously seeking knowledge is led to something else. He finds no starting point for gaining ideas for the I anywhere in the world around us. As a rule, what surrounds us is sometimes outside and sometimes inside in the soul. Basically, it is the same. And if we can only find a hole for the ego within, we cannot find a point of reference outside, even under ordinary circumstances, where we can place our ego, so to speak.

Those who seriously strive for knowledge find a way to approach the ego in the events of the world only with one phenomenon: that of death. It is precisely at the point where the human being ceases to exist at death, when, as it were, the human body is surrendered to the external forces from which

it was withdrawn from birth or from conception to death, then, when we are now in a position to form an idea of the human being, now that we no longer have the possibility of drawing conclusions about the human being from the body, only then does the possibility begin for us to approach the ego. We must begin with the phenomenon that is, so to speak, most inexplicable among the external phenomena, most inexplicable because it can no longer be grasped by ordinary consciousness, and can least be brought into consciousness.

But if we can decide to look at death in this way, if we do the same with the phenomenon of death as I have described for the struggle with concepts in general, where mere abstract knowledge becomes an inner experience, if we approach the phenomenon of death in this way, then we gradually learn to see through that death, when it confronts us at the cessation of life, is actually only something like a sum, like an integral, I would say, of individual processes that always take place in man from birth on. We are always dying, but we die in very small portions, so to speak. When we begin our life on earth, we also begin to die. But again and again, and again, what is given to us as vitality through birth overcomes death. Death always wants to work in us. It only ever manages a very small portion of its work and is then overcome. But what seems to us to be vividly compressed in death at that one moment is constantly taking place in life, like differentials, and is a continuous, ongoing process.

If we follow this, we see that in the human inner organic process, there are not only anabolic processes. If there were only anabolic processes, we would never be able to achieve thinking consciousness, because that which merely lives, that which is merely vital, takes away our consciousness, makes us unconscious. The death processes in us, the dying processes, the destruction processes of the vital, which always take place differentially in us, are what bring us consciousness, what make us thinking, level-headed beings. We would always fall into a kind of rashness, into a kind of unconsciousness, if we only lived. If it were true that life in plants is at a certain level, in animals at a higher level, and in humans at an even higher level, if it were always a matter of an increase, of a potentization of life, we would never develop a thinking consciousness.

We have life in plants. But as life ascends to animals, it already begins to subside in animals. But in humans, there is a continuous dying process. This continuous dying process, which not only dampens life but undermines it – it is only rebuilt in turn – is the organic process that underlies conscious thinking. To the extent that we have the continuous process of dying within us, we have the possibility of thinking in our physical life.

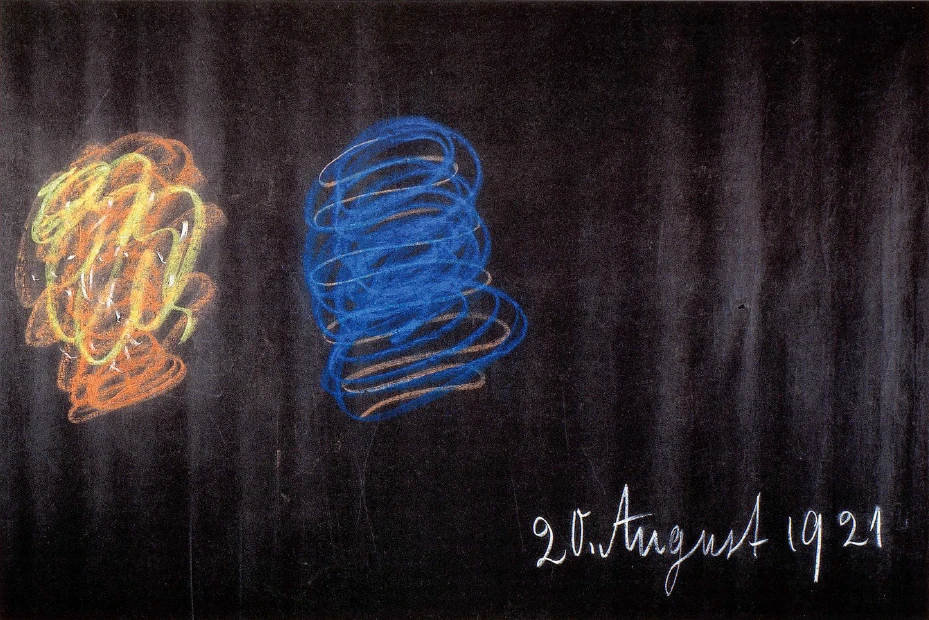

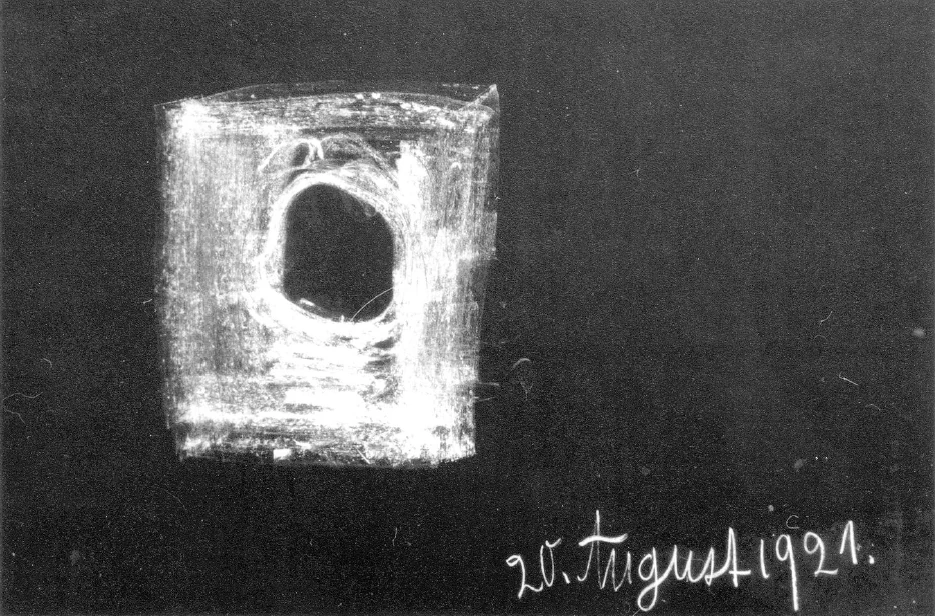

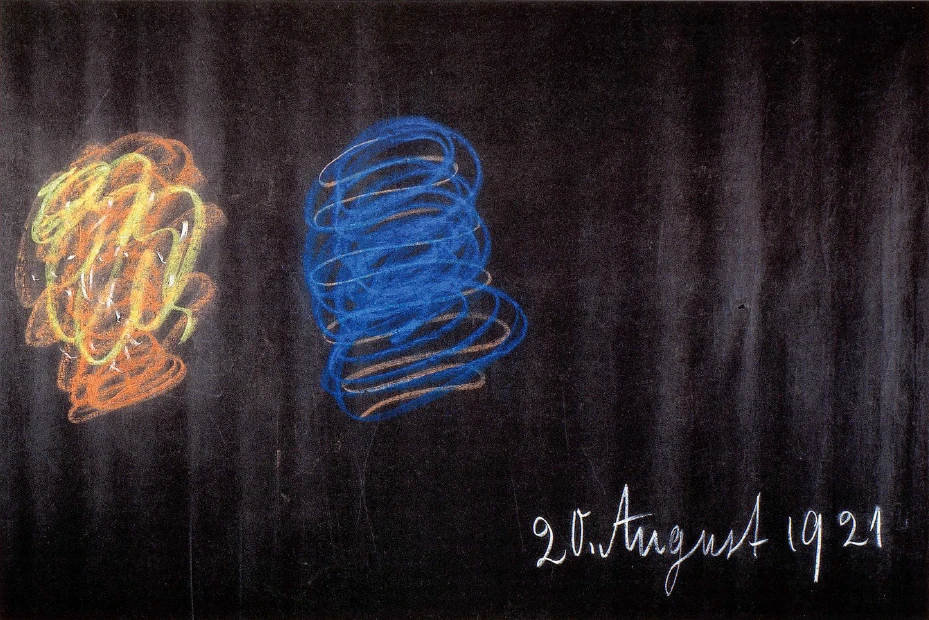

But if we learn to observe, we can see the building process (see drawing, red), the vital building process of the vegetable kingdom, which also works in us. one then understands how this anabolic process is dampened by the animalistic (green), but how a continuous falling out (black) takes place, an inner decay, and if one finally rises to have a realization of this inner decay, then one also has that which always maintains itself against this decay. One has the process of dying, but one also has a perpetual fighter against the process of dying; one has the process that represents the life of the ego.

That is where the ego lives. By seeing, in higher knowledge, in higher contemplation, how a continual depositing takes place through the nervous process of man, how, as it were, an inner sediment is formed, one also sees how the I continually wrings itself out of this sediment formation, out of this inner sediment formation. One cannot gain a view of the true self until one is able to observe this inner sediment formation. The self lives in the human being, of course, but the human being perceives this self by experiencing the process of dying, the process of inner decomposition. And the one who has now grasped how the ego is a constant fighter against this process of dying has grasped how the ego is something that as such has nothing to do with death at all; he has vividly grasped what otherwise designated dialectically or logically as immortality.

But this is the way to see immortality, because it leads to entities that belong to a different order of existence from that which precipitates as sediment. One arrives in a region where death has no meaning, where death loses the possibility of being formed as an earthly sensation. Thus we approach the I when we study death. I have only hinted at this, for this study of death is a very detailed one, and for those who attach a certain importance to it, it can also be said that the pursuit of this perpetual sedimentation, this formation of sediment, in contemplation appears as if there were a perpetual continuous inner flaring up of sparks of darkness, thus in contrast to sparks of light: sparks of darkness in an even luminous aura.

But we must form other concepts if we want to approach what can lead us to a kind of knowledge of the human being. I must start from something else if I want to form this other concept. I had to refer you to death and how to overcome it, because the aim was to get to the ego. I would now like to refer you to the following: consider the life of plants, but first of all the actual plant. This is the annual plant, because in the perennial plant and in the tree we are already confronted with a complication that would necessitate a separate consideration. In the annual plant, you find the germinating of growth from the seed, the shooting of the leaves, the emergence of growth up to the flower, up to fertilization, the development of the fruit containing the seed for the following plant. We see, as it were, the result of the fruit, which in turn develops into a plant.

You will easily be able to imagine that the plant, as it develops from those early stages where the leaf emerges, to fertilization, unfolds forces within itself that reach their culmination at the very moment of fertilization. But then the downward path begins, and the plant decays again. And by observing this cycle of the plant world, you will see the essential nature of the plant. As I said, we will not deal with perennial plants and those plants that leave behind a trunk like a tree. What I said about the annual plant, which comes to an end with a single fertilization, would only be more complicated; but we grasp the essential nature of the plant by looking at the nature of the plant that comes to an end with fertilization. When properly observed, the plant-like quality lies precisely in the life that culminates in fertilization and, by culminating in fertilization, descends in the other direction. Therein lies the plant-like. If we seek the essence of the plant, we must search in a similar way to how we must search for the human being's sense of self in the continuous dying. We say of the human being that the death with which he first ends his physical being is actually always within him as a force. When he is born, he begins to die, begins to develop, I would say, differentials of dying; he dies continually. The dying process is within him. In the plant, that which culminates last is continually present. Just as we culminate in death, so they culminate in fertilization. Just as we grasp our inner being, our ego, in death, so we grasp the essence of the plant in fertilization. The plant comes to life in fertilization; what develops in the leaf is only a metamorphosis, only a preliminary stage of fertilization.

When you come to animals, the situation is as follows: the animal is fertilized, but at first the fertilization does not mean withering, but it can be fertilized again. Of course, we always come to borderline questions, but we want to grasp the living and feeling in certain characteristic main points. Just as the plant being, the actual plant being, culminates in fertilization – of course, anyone can doubt that this is the actual plant being, but we grasp the plant being where it manifests itself – so the animal does not culminate in fertilization, but overcomes fertilization. That which is the higher animal carries something else within itself. If it were to carry only that which lives in fertilization, it would have to undergo the same thing as the characteristic plant: it would have to die. But it carries something beyond fertilization. And when we come to man, he not only overcomes what the animal overcomes, but he overcomes death itself.

These things of which I have now spoken should not be taken dogmatically; nor should they be taken in such a way that one formulates definitions from them, for then one immediately goes astray. But if someone were to say that a plant is what perishes in fertilization, and that an animal is what retains something beyond fertilization, then they are formulating definitions instead of acquiring concepts. One can only come to an understanding if one acquires concepts for certain stages of life and existence. And just as one must acquire the concept of the ego by bringing the ego to death, so one must acquire the concept of the animal by observing how fertilization is overcome in something that lives in the animal beyond fertilization. One must observe the plant, regarding fertilization, or rather what takes place in fertilization, as a continuous process.

But then, when one has risen to such concepts, these concepts themselves become something living in the soul life. And these concepts, once grasped, themselves fertilize the soul life. So that we are now in a position not only to grasp the human being's ego, but also, by appropriating what remains in the animal beyond fertilization, we gradually arrive at a concept of the human being's astral body. And when we appropriate what lives continuously in fertilization, we also arrive at a concept of the human being's etheric body. If we grasp the actual I as that which escapes this sedimentation, then we must grasp the astral body in a different way. We must grasp this astral body in the following way. Let us not consider what grows, feeds and reproduces as dying away. We consider the whole physical being as dying away when we want to come to the I. So now we consider that which grows, which reproduces, not as dying, but only as continually paralyzed, so that there is now not something that conquers death, but something that conquers the paralysis of vitality, which thus, whenever vitality sinks, always again whips up this vitality

Then we have, just as here (see drawing page 195) dark sparks spurt out of the light, here (see drawing page 200, red) there is continually a dark (blue) clouding, if I may say so, clouding out of a bright color glowing. One must use these expressions in order to have ideas in these parts of being. I would like to say that the I sparks out of the light, it clouds out, tinting, cloudily tinting a light tint, when the astral element in the etheric element conquers the dulling of the vitality. I am trying to be as precise as possible, but you understand that these things, which are no longer accessible to intellectualistic knowledge but only to the imaginative, cannot be expressed by intellectualistic concepts either, but that they have to be expressed through imagination.

It can also happen, can't it, that people take such imaginations for the thing and then don't know their way around, as certain critics of anthroposophy do. But these people make the mistake that someone would make — as paradoxical as it is, but it is so — who, when someone says the word 'hedgehog', imagines a real, prickly hedgehog. The word 'hedgehog' is, of course, not the hedgehog. Just as little as these images are the corresponding being, but we can only penetrate through these images to what is really there in the supersensible being. Ultimately, it is a sensualization.

Those who are familiar with the whole process do not, of course, need to be told what Bruhn, for example, says in his little book about anthroposophy: that anthroposophy confuses the supersensible with the sensual. That is about as clever as accusing a mathematician of confusing what he writes on the blackboard with mathematics. But that is how criticism is usually written about what one does not want to understand, because one does not want to choose the paths to it that are necessary. So what it is about is that we have to find our way back to what can bring the human being before our soul again. Imaginations once occurred in the course of the breathing process; imaginations must again arise through which we can approach the true nature of the human being. Only we cannot reach them through a breathing process, but through those processes which I have tried to describe in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds” and in my “Occult Science”.

I wanted to give you some hints today about how another soul condition must be sought out of today's intellectual soul condition. This other soul-condition is not the same as the consciousness of direct vision. It is not at all necessary to attain the consciousness of direct vision, but this other soul-condition can be had. It develops out of a truly intellectualized inner development, when one is in earnest and sincere about this intellectualized inner development and knows where its limits are. Then it will develop without fail. And the person most likely to arrive at such a view of an inner metamorphosed state of mind is the person who is living in the scientific concepts of modern times. For if he lives into them in such a way that one can live with them, if he does not merely humbly accept them, but if he lives into them in such a way that one can really live through them inwardly, then he will not be led by them to an ignorabimus, but will be led to a special experience, to a real struggle, precisely at the boundary where otherwise the ignorabimus is placed, is impaled. And so this other state of mind is kindled. But everything depends on approaching the scientific concepts themselves in an honest and thoroughly truthful manner. Then one does not stop at them, they become germs from which something else grows; then one does not stop at laying these scientific concepts next to each other and looking at them, but one sinks these bean germs into the earth, that is, the intellectualistic concepts of nature into the depths of the soul. There they flourish in a new state of mind. What has been developed over the past few centuries carries within it the potential to give rise to new seeds of knowledge. We have to look at an age that, in turn, reveals a different state of soul from that which the age of Galileo, the 15th century, brought forth. We have to advance to a deeper knowledge of the world by coming to a more intense experience of our own human interior.

Source: August 20, 1921

No comments:

Post a Comment