|

Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland, April 11, 1920:

In these studies I wanted to draw your attention to certain things which can lead us back to a more concrete study of the Universe than is contained in the cosmogony of Copernicus. We must not forget that the Copernican cosmogony arose during the epoch after the middle of the fifteenth century when there was an increasing tendency toward an abstract conception of the Universe. It came indeed at a moment of time when the tendency to make everything abstract was at its height. We must also remember that it is essential now that we should get free of this tendency and bring to our thought about the Universe concepts that contain something more than mere abstract ideas. It is not a matter simply of constructing a cosmogony similar in kind to that of Copernicus, on slightly different lines. This was brought home to me in the questions arising out of the last lecture. For the point in these questions turned on the possibility of being able at once to draw lines that would give us a picture of the world — once more a picture in quite external abstractions. That of course is not what is wanted. What we have to do is to grasp in its spiritual nature all that is not man, in order to build a bridge from the spiritual in Man to the spiritual outside him. You must understand that here, at this particular time at all events, it cannot be our task to discuss a mathematical astronomy. That would necessitate beginning over again from the very rudiments; for the fundamental concepts employed today have their source in the whole materialistic mode of thinking in use since the middle of the fifteenth century. If we wanted to develop and complete the cosmogony we have sketched, it would be necessary to begin with the most elementary principles and elaborate them anew. The fate that befell Copernicanism came about, as we shall see, because of the strong tendency to abstraction, which may so easily lead to intellectual excesses. True Copernicanism is not really the same as that which it has become in the hands of the followers of Copernicus. Certain theories have been selected from Copernicanism which were quite in keeping with the ways of thought of the last few centuries, and from them the cosmogony now taught in all the schools has arisen.

It is not my wish to do anything in the direction of a similar cosmogony, where, instead of the well-known ellipse in which the Sun is placed as one of the foci, and in which the Earth moves with an inclined axis, we simply put a screw-shaped line! What I want rather to do is to present the relation of Man to the Universe, and it is in this direction that we will now pursue the matter further.

I have tried to show you how, the moment one begins to pass to a more intensive experience of the three directions of space in one's own form, one realises how these directions differ in nature and kind from one another; it is only the faculty of mental abstraction in the head which makes these three dimensions abstract and does not distinguish between above and below, left and right, before and behind, but simply takes them as three lines. And a similar error would immediately again be incurred if one set out to build any other construction into space in a purely abstract way. The point at issue can be made clearer if for a moment we turn to something else.

Let us consider colours. We will take colour once more as an example. Suppose we have a blue surface and, let us say, a yellow one. The conception of the world which, in its abstract thinking, gave rise to the Copernican cosmogony, has indeed succeeded in saying: “I see before me blue, I see before me yellow. That is due to the fact that some object has made an impression on me. This impression appears to me as yellow, as blue.” The point is that we should not begin to theorise in this way at all, saying: “Before me is yellow, before me is blue, and they make a certain impression upon me.” That is really just as if you were to treat the word PICTURE in the following way. Suppose you were to set about making deep researches into the word and think: “ ‘P’, something must be at the back of this; behind ‘P’ I must seek the vibrations which cause it. Then again, behind the ‘I’ there must be vibrations, and behind the ‘C’ more vibrations, and so on.” There is no sense in this. We find sense only when we unite the seven letters, connecting them one with another in their own plane, and read the whole word ‘Picture’; when we do not speculate as to what lies behind, but read the word — ‘Picture’. So here too the point is that we should say: “This first surface makes me penetrate, as it were, behind it, makes me plunge into it. This other surface makes me turn away from it.” It is to these feelings into which the impression passes over that we must pay attention; then we come to something concrete. If we thus seek in the world outside what we experience inwardly, we come indeed to the feeling that we are not really within ourself at all, but that with our real ego we are in the Universe, poured out into the Universe. Instead of searching behind the external Universe for ‘vibrations’, the atomists should seek for their own ego behind the phenomena and then try to find out how their own ego is placed into the outer Universe — is, as it were, poured out into it. Just as with colour we should try to ascertain whether we feel we must plunge into it or whether we feel ourselves repelled by it, so, as regards the structure of our organism, we should feel how the three directions, above and below, forwards and backwards, right and left, differ concretely from one another; we should feel how differently we experience them inwardly, when we project ourselves into the Universe. When we are aware of ourselves as Man standing on the Earth, surrounded by the planets and fixed stars, we begin to feel ourselves as part of all these; it is not a matter merely of drawing three dimensions at right angles, but of thinking concretely about the Cosmos and penetrating into the concrete reality of the dimensions.

Now, there is a series of constellations that is immediately evident to those who study the outer Universe at night-time, and has indeed always been seen when men have studied the stars. It is what we call the Zodiac. It is immaterial whether we believe in the Ptolemaic or the Copernican system; if we follow the apparent course of the Sun it always seems to pass through the Zodiac in its yearly round. Now if we imagine ourselves placed into the Universe in a living way, we find that the Zodiac is of very great significance. We cannot conceive of any other plane in celestial space as being of like value with the Zodiac, any more than we could conceive the plane which divides us in two, and creates our symmetry, as being placed at random just anywhere. We then perceive the Zodiac as something through which a plane may be described. (Drawing.) Let us suppose this plane to be the plane of the blackboard, so that we have here the plane of the Zodiac; the plane of the Zodiac is just the plane of the blackboard. We shall then have one plane before us in Cosmic space, precisely as we imagined the three planes sketched in Man. That is certainly a plane of which we can say that it is fixed there for us. We see the Sun run its course through the Zodiac; we relate all the phenomena of the heavens to this plane. And we have here an analogy of an extra-human kind for what we must perceive and experience as planes in Man himself. Now, when we draw the Symmetry plane in Man, and have on one side of the Symmetry-axis the liver organised in one way, and on the other side the stomach organised in a different way, we cannot think of such a fact without feeling at the same time some inner concrete relation; we cannot imagine mere lines of space lying there, but what is in the space must manifest definite forces of activity; it will not be a matter of indifference whether something is on the right or on the left. In the same way we must imagine that in the organisation of the Universe it is a matter of consequence whether a thing is above or below the Zodiac. We shall begin to think of Cosmic space — as we see it there, sown with stars — we shall begin to think of it as having form.

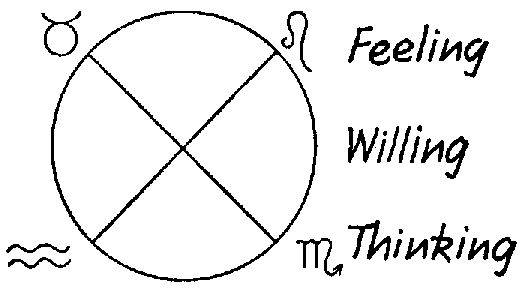

Now, just as we can think of this plane on the blackboard, so we can also think of another at right angles to it. Let us think of a plane extending from the constellation Leo to that of Aquarius on the other side. Then we can go further and imagine a third plane at right angles again to this one, running from Taurus to Scorpio. We have now three planes at right angles to one another in cosmic space.

These three planes are analogous to the three we have imagined described in Man. If we think of the plane we have denoted as that of Will — the plane namely which separates us behind and before — we have the plane of the Zodiac itself.

If we think of the plane running from Taurus to Scorpio, we have the plane of Thinking; that is, our Thought Plane would be coordinated to this plane. And the third plane would be that of Feeling. Thus we have divided Cosmic space by means of three planes, just as we divided Man in our first lecture.

What is primarily of importance is not simply to unlearn as quickly as possible the Copernican cosmic system, but to enter into this concrete picture, to imagine cosmic space itself so organised that one can distinguish in it three planes at right angles to one another, just as can be done in the case of Man.

The next question to arise for us must be: Is really the whole of Man to be thought of as forming an integral part of what appears to us as an outer Cosmogony, in which Man is included? We emphasised in the last lecture that the Earth with the Sun and other planets progress in a spiral. Such a statement is, of course, merely diagrammatic, for the spiral line itself is curved. That however does not concern us here; what is important for us at the moment is that the Earth, as we have seen, follows the Sun in such a spiral, and the question is whether Man too is so interwoven in this movement that he is absolutely compelled to take part in it in any case; for if that be so, if he absolutely must follow completely, then there is no place at all for free will or for moral activity on his part. Let us not forget that we began our study with this very question: how to build a bridge leading from pure natural necessity to morality, to what takes place under the impulse of free will.

Here we can go no further if we rely only on the Copernican system; for what have we there? We picture the Earth upon which we stand; whether the Earth or the Sun goes rushing along is of no moment ... If Man is connected with all this in an absolute natural causality, it is impossible for him to develop free will. We must therefore put the question: Does the entire being of Man lie within this natural causality, or does the being of Man move up out of it at some point? We must not however put the question out of the mood of thought of the materialists of the nineteenth century, who remarked that so many people have died on Earth that it would not be possible to find room for all their souls. They wanted to know about the space required for souls. But the point in question really is: What meaning is there in asking about a place for souls?

We must above all clearly understand that the full sense and meaning of the events in the Universe — and movement is also an event — only becomes clear to us when we grasp it in definite cases. We distinguish in some way what takes place in the four realms — what is above and below the plane of the Zodiac (Will), and what is right and left of the plane of Feeling; or again, we can consider what lies on this or on the other side of the plane of Thinking. We feel that something is connected with this differentiation, something of cosmic happening, namely, that which manifests in recapitulation, as we have it for instance in what we designate as the “course of the year”. And we must now ask in a concrete way: How can we find a connection between Man and the yearly course of the outer Universe? Well, first of all we find that when Man descends from the spiritual world into the physical, he passes through conception. He remains for about nine months in the embryonic condition — that is to say, three months less than the year's course. We might be inclined to call this a very irregular proceeding. In his evolution Man seems to show, even at the very genesis of his physical earthly existence, that he pays no attention to the course of cosmic events outside. This is however not the case. If we have the faculty for observing the child during the first three months of his earthly existence, we find that these first three months — which make the year complete — manifest in a very true sense a continuation of his embryonic life; what takes place in the brain, as well as other things happening with the little child, can from a certain aspect be considered as still belonging to its embryonic life. Thus we can say that in a certain respect the first year of human development can after all be identified with the year's course.

Then comes another year — or about a year. If we observe the child after the first year, we see that the second year is approximately the time of the growth of the milk teeth. We observe the child during the second year after its conception, and we find that this year corresponds on an average with the growth of the first teeth. Now let us ask, does this continue? No, it does not. The first ‘teething’ seems to represent an inner year of Man. And so it does, just as the first year is at the same time an inner year of Man. In the formation of the milk teeth, the Universe obviously works in the child. But then something different happens.

In a space of time seven times as long — it is indeed far from completion even then, but at least it begins its activity during this period — in a period seven times as long from birth, the force which pushes out the second teeth is at work in the child. Here something occurs which we can not connect with the world's course but with something that is withdrawn out of it, and works from the inner being of the child.

Here, then, we have a concrete instance. We have, first of all, in respect to one series of facts, the world organism projected into Man in the formation of his milk teeth. And then again, when we look at the permanent teeth, which grow forth from Man, we find that these are Man's own production. An inner human cosmic system has placed them into the other cosmic system. Here we have the first herald of Man's becoming free, in the fact that he engages in something which clearly shows his independence of the Universe; because although this process retains within it in Man's being the time-course of the Universe, Man has slowed it down within him, he has given the same process a different velocity, seven times as slow, thus taking seven times as long. Here we have the contrast between the inner being of Man and the outer being of the Universe.

Another independence of the outer Universe is very clearly demonstrated in the alternation between sleeping and waking. Positions of the Earth alternate in respect to certain constellations, but they alternate always with day and night. How is it with Man?

What does this alternation between waking and sleeping signify to us human beings? It means, roughly speaking, that we go about at one time with our ego and astral body united with our etheric and physical bodies, and at another time with the ego and the astral body separated from the etheric and physical bodies.

Now a man in the present cycle of civilisation, especially one who calls himself a civilised man, is no longer entirely dependent in this respect on the cycle of Nature. The cycle of waking and sleeping, in its measure of time, seems to resemble the cycle of Nature; but there are persons at the present time — I have known such! — who turn night into day and day into night. In short, Man can wrest himself free from connection with the world's course. The sequence in him of the sleeping and waking states shows however that he still has within him a copy of this conformity to law. The same is true of many phenomena of the human being. When we observe how Man alternates between waking and sleeping, and Nature alternates between day and night, and how Man is still today bound to the alternation of waking and sleeping though not to that of day and night, we must say: Man was at one time, as regards his inner conditions, bound to the outer course of the Universe, but he has broken away from it. Civilised Man today has almost entirely broken away from the course of outer Nature. He is really returning to it when he perceives, when he discovers with his intellect, that it is better for him to sleep at night rather than by day. It is not the case however, that night takes possession of Man in such a way that he must under any circumstances sleep. No civilised man really feels: ‘Night makes me sleep, day wakes me up.’ At most, if night falls and a lecture is still going on here, the two facts taken together may perhaps affect some in such a way they experience an absolute demand of Nature that they should fall asleep. These however are incidents not necessarily involved in our cosmogony.

Thus the point to observe is that Man has wrested himself away from the course of Nature, but that nevertheless in his periodicity he still shows a reflection of it. Let us see how transitions from one to the other condition manifest themselves. We may say that in our waking and sleeping we still distinctly show the course of Nature in picture, but that we have wrested ourselves free from it. In the appearance of the second teeth, we no longer show in chronological sequence a picture of the course of Nature such as is still expressed in the growth of the first teeth. When we receive our second teeth, a new course of Nature arises in us; for this is not in our control like sleeping and waking. Our free choice does not enter here. Here something appears belonging to Nature and yet not following the larger course of Nature, something which Man has for his own. And yet it is not within his free choice, it is inserted as a second natural organisation within the first.

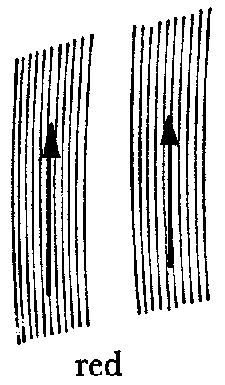

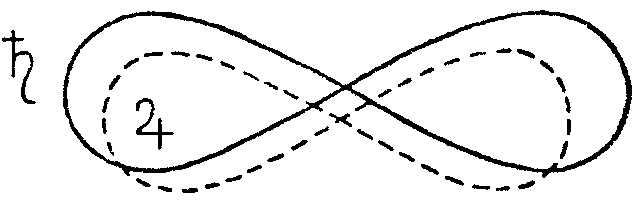

In all these things, I am speaking of quite simple everyday matters, but it is a question of noticing them in the right way. We must now say to ourselves: There is a certain natural ‘happening’, within which is interwoven the growth of the first teeth. Let us draw it in diagram. Within this natural event or process, as a part of the process, goes forward the formation of Man's first teeth. Then we have another natural happening, one of Man's own, not all within the general happening of the world — the growth of the second teeth (red). To draw it, we must present it as a different stream. Yet the difference is not yet clear in the drawing; they both look alike. The fact is, we must represent

it in a quite different way if we want to depict the connection between the receiving of the first and second teeth; we must draw the first teeth seven times deeper in. If we draw them side by side, parallel, we have no picture of the relation of

the first teeth to the second; we only get a picture of the force upon which the growth of the first teeth depends by drawing it encircled by another force, upon which the growth of the second teeth depends. Here, through the difference of velocity, the necessity arises for the movement to curve. Thus, when we say that there is a star somewhere in space with another circling round it ... then through the simple fact of the revolution, something qualitative arises — a creative activity.

I might also say: we look at the growth of the first teeth and of the second; that must have something to do in cosmic space, with certain forces, one of which circles round the other. I put this example before you, because from it you will see what it means to speak of concrete movements in space, and how empty is the kind of talk which says: Jupiter — or, it may be Saturn — is so and so many miles distant from the Sun and encircles it in such and such a line. That tells one nothing at all, it is an empty phrase. We can only know anything about facts like these when we unite some content with them, such as: the orbit of Jupiter is like this, the orbit of Saturn like that, and the revolution of the one serves the revolution of the other.

I have here merely pointed out the necessity for certain definite processes and happenings. Some of you may say that they are difficult to understand. Or perhaps you will not say so, but will consider that there is no need to discuss them! Not until people learn to study such things will they be able to progress to a definite and clear view of the Universe. And then they will give up what is presented so superficially in Copernicanism — the conception of the celestial movements solely in lines. Rather should an impulse enter humanity which says: It is necessary to be clear first about our own most elementary experiences before turning our attention to the outer mysteries of the Universe.

We only learn the significance of certain connections which we read from the stars when we understand the corresponding processes in our organism; for what lies within our skin is no other than a reflection of the organism of the outer world. Thus if we draw a man in diagram, we have here the blood circulation (in diagram only) and we can trace its path. It is all in the inner being of Man. If we now go out into the Universe and look for the Sun, it is the Sun which corresponds to the heart within Man. What goes out from the heart through the body, or in point of fact out from the body to the heart, does in truth approximately resemble the movements connected with the course of the Sun. Instead of drawing abstract lines, we should look into the human being. Within his skin would be found what is outside in celestial space. Man too would be found to have his part in the cosmic order. And, on the other hand, his independence of the cosmic system would also be seen; and how he gains this independence little by little, as I have shown. We will speak further about this in the next lecture; for the present we must realise that we are dealing with it here merely in a diagrammatic way.

Look at the principal course of the blood vessels in the human organism. Seen from above it is like a looped line. Instead of drawing it, we should follow the hieroglyphs inscribed in our own selves; for then we would learn to understand the nature of the qualities in the Universe outside. This we can only do when we are able to recognise and experience livingly the fact of which I have also spoken in public lectures, the fact namely, that the heart does not work like a pump driving the blood through the body, but that the heart is moved by the circulation, which is itself a living thing, and the circulation is in its turn conditioned by the organs. The heart, as can be followed in embryology, is really nothing more than a product of the blood circulation. If we can understand what the heart is in the human body, we shall learn to understand also that the Sun is not, as Newton calls it, the general cable-pulley which sends its ropes (called the force of gravitation) toward the planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and so forth, drawing them by these unseen forces of attraction, or spraying out light to them, and the like; but that just as the movement of the heart is the product of the life-force of the circulation, so the Sun is no other than the product of the whole Planetary system. The Sun is the result, not the point of departure. The living cooperation of the solar system produces in the centre a hollow, which reflects as a mirror. That is the Sun! I have often said that the physicist would be greatly astonished if he could travel to the Sun and find there nothing of what he now imagines, but simply a hollow space; nay, even a hollow space of suction which annihilates everything within it. A space indeed that is less than hollow. A hollow space merely receives what is put into it; but the Sun is a hollow space of such a nature that anything brought to it is immediately absorbed and disappears. There in the Sun is not only nothing, but less than nothing. What shines to us in the light is the reflection of what first comes in from cosmic space — just as the movement of the heart is, as it were, what is arrested there in the cooperation of the organs, in the blood-movement, through the activity of thirst and hunger and so forth.

If we understand the processes in the inner being of the organism, we can also understand from them the processes in outer cosmic space. The abstract dimensions of space are only there to enable us to follow up these things in an easy, indolent way. If we wish to follow them up in conformity with the truth, we must try to experience ourselves inwardly, and then turn outward with inner understanding. They understand the Sun who understand the human heart; and so it is with the rest of Man's inner being.

Thus it is a matter of supreme moment to take the saying ‘Know Thyself’ seriously, and from that to pass on to the comprehension of the Universe. By a self-knowledge which embraces the whole Man, we shall understand the Universe outside Man.

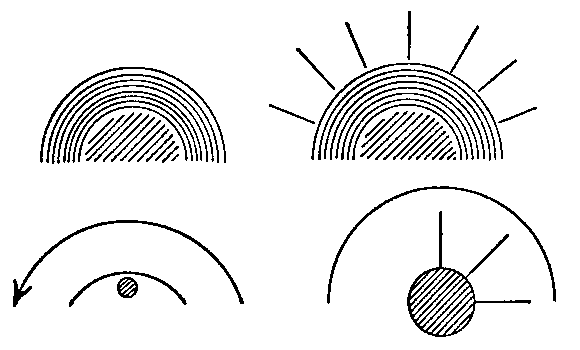

You see we cannot get on so quickly with the construction of a cosmogony! In order to make a few of the features of this cosmogony clear, we can draw a spiral; but this does not yet show the actual state of things. For to describe a few more features, we must make the spiral itself move spirally; we must make the line itself curve. And even then we have not come far, for in order to describe certain facts such as the difference between the growth of the first year's teeth and the growth of the seven years' teeth we must describe a displacement of the line itself.

So you see that the construction of a Universe is not a thing that can be done very quickly. The wish to construct a cosmogony with a few lines must be relinquished, and man must learn to regard the present conception of the world as an absolute delusion.

This is intended as a preparatory study for what I mean to say in the next lecture. It had to be rather more difficult; but when we have overcome these initial difficulties, we shall have constructed the preliminary conditions for uniting the three important domains of life — Nature, Morality, and Religion — by means of two corresponding bridges.

Source: https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA201/English/RSP1972/19200411p01.html

No comments:

Post a Comment