Source: October 18, 1905

"Spirit Triumphant! Flame through the impotence of fettered, faltering souls! Burn up selfishness, kindle compassion, so that selflessness, the lifestream of humanity, may flow as the wellspring of spiritual rebirth!" — Rudolf Steiner

Source: October 18, 1905

My Dear Friends!

The studies we have been pursuing together in these past days have led us to see that two things are necessary if we want to be artists on the stage. In the first place, we must be ready and willing to undertake an intensive study of the elements of the arts of speech and gesture — those first elements of which we have seen that they are rooted and sustained in the life of the spirit. And then secondly, we must give to dramatic art its right place in the whole compass of our life, and in so doing implant in our hearts a mood that is permeated by spirit and never deviates from the paths of spirituality. If we can fulfil these two things required of us, then we shall be able to take our part as actors in the life of mankind in the way that an artist should who is sustained and upheld by the spirit. For such an artist should have it in his power, by means of all that he is and does, to help bring the artistic into that leading role in civilisation to which it is called, and for lack of which civilisation must inevitably wither and perish.

Such was, I know, the earnest aspiration that prompted a number of you to ask for this course of lectures. And we shall need to carry the same earnestness into our further study, as we go on now to consider, for example, how the human form is a revelation of the great world. Approaching the theme from the standpoint of the art of the stage, we shall have to find how in the form and figure of man, taken in its most comprehensive sense, the universe is revealed — significantly, intensively revealed. And the perceptions that light up within us through thus beholding man as a revelation of the universe will guide us in linking up again the natural and elemental with the divine and spiritual.

We will accordingly begin our lecture today with a consideration once again of the question: How can we see in the forming of word and of sound a revelation of the form and figure of man? If we think of ‘speaking’ man, man revealing himself in speech, then the first part of his form that calls for notice is his lips. It is, to begin with, the lips that do the revealing.

Disregarding altogether for the moment the grouping of the consonants into impact sounds, breath sounds, wave sounds, and vibrant sounds, we find that the sounds which are brought to expression by means of the lips are m, b, p. These sounds are revelations that are made entirely by the formative activity of the lips; both lips are engaged.

1. Both lips engaged : m b p

If we try to utter any other sound than these with the lips, we not only interfere with the right forming of speech, we do injury to our organism. And if on the other hand we speak m, b or p without the complete instinctive consciousness that here the lips are the specific agents, then again we harm both our speaking and our organism.

A second activity reveals itself when we begin to look a little way in from the lips — a cooperation, namely, of lower lip with upper teeth. In the muscles of the lower lip we have an intense concentration of our karma, of that karma that is so mysteriously present within us all the time. The forces that work and weave throughout the limbs go streaming through the muscles of the lower lip in a wonderful variety of movement; we may even say that the whole human being, with the exception of the organisation of the head, comes to expression in the activity of the lower lip.

In comparison with those of the lower, the muscles of the upper lip are inactive. Their part is rather to provide opportunity for what is contained in the head organisation to find its way into the muscular system. And whilst the lower lip is positively no less than a complete expression of man as limb-man, all that can be said of the upper lip is that it supplies man in its movement with a means of expression for what is contained in the utterance of m, b and p.

But now, through this cooperation of lower lip and upper teeth we can bring to expression what comes more from the entire man. The upper teeth, like the upper lip, bring the head organisation to expression, and being more at rest and circumscribed, are able to do so even better. In the upper teeth we have a concentration, a consolidation, of all that man is ready and willing to receive of the secrets of the universe, those secrets that crave to be taken hold of in this way, to be established and consolidated in man's being. There in the upper teeth they come to rest. And when we let lower lip and upper teeth work together in the right way in f, v (f) and w (v), then what has been received by us from the whole sum of world secrets and is now wanting to come to expression finds that expression.

2. Lower lip and upper teeth: f v w

The South Germans are almost unable to say w; they pronounce it like u and e run together, giving it the character of a vowel. W properly spoken arises from the lower lip meeting the upper teeth in a kind of wavelike movement, whereas in v the lower lip merely closes up to them without this wavelike movement. In f the lower lip pushes with all its force on to the upper teeth.

A further stage is reached when the two rows of teeth work together. This means that the lower and upper organisations of man, the organisations of head and of limbs, are held in balance. The world has, so to speak, been captured by man, he has it there within him; and now he on his part wants to send forth his own being into the world without. This is how it is when we attain to a right interworking of upper and lower teeth in speaking the sounds s, c (ts), z (ts).

3. Upper and lower teeth working together : s c z

In these sounds, the teeth alone are concerned.

Entering now still farther into man, we come to his inner life, to where his life of feeling seeks to express itself, his life of soul; we have therefore also to go farther back in his bodily being. We come then to the tongue; and we have first the revelation that can come about through tongue and upper teeth working together. Whilst what man has become by virtue of all that he has received from the world reveals itself in the interplay of lower lip and upper teeth, what man is by virtue of the fact that he has a soul, comes to revelation in the interplay between soul and head — that is, between tongue and upper teeth.

Here, therefore, the tongue begins to work — and behind the upper teeth. Please take special note of the word "behind." This gives rise to the sounds: l, n, d, t.

4. Tongue works behind the upper teeth: l n d t

If we are to succeed in producing in our pupils healthy and beautiful speaking, it will be important to arrange in our dramatic school for the practice of exercises expressly designed to avoid lisping. In lisping, the tongue ventures too far forward, pushing itself between the teeth. The students must succeed in having the tongue so completely under control that the cardinal maxim of all speaking is consciously carried out, namely, that the tongue shall never be allowed to overstep the boundary set by the two rows of teeth.During the whole time of speaking, the tongue must stay behind this boundary. When it is allowed to come out beyond the teeth, it is as though the soul were wanting to come forth and expose itself, without body, to immediate contact with Nature.

A person who lisps should accordingly be given the following exercise, and one should begin it with him as young as possible. Get him to practise saying n l d, repeating each sound three times, and each time resolutely pressing the tongue on to the back of the upper teeth: n n n, l l l, d d d. To continue uttering the sounds in this way, one after the other, is difficult, but that is how they should be practised. It is a fatiguing exercise; it may well leave the pupil feeling as though he were seized with cramp. But let me tell you how the first man to draw attention to this exercise used to encourage his patients. He would remind them of the lieutenant who was in the habit of saying to his raw recruits: ‘Of course it is difficult; if a thing isn't difficult, you don't have to learn it!’

The fifth thing we need to consider lies still farther back in the mouth. We have to learn to be fully conscious of the part played in speaking by the root of the tongue. That is then the fifth, the root of the tongue. We shall here have to practise the sounds g, k, r , j , qu (kv), speaking them as far back in the mouth as possible, and consciously feeling, as we utter them, the root of the tongue.

5. Root of the tongue: g k r j qu

It is these sounds — and more especially g, k, r — sounds where we have to take pains to be conscious all the time of the root of the tongue, that must bear the blame for stuttering. Stuttering arises when the instinctive feeling of the proper way to say g, k, r is lacking. We will go into this matter a little further presently, but directly you notice signs of stuttering in a pupil, you will have to take him with g k r and try to get him to speak these sounds to perfection. For r you can administer a physical help. Instead of expecting your pupil to produce r right away by his own inner effort, prepare him beforehand by letting him gargle water sweetened with sugar. Yes, as you see, whenever there is something of this kind that can help a pupil, something quite external, I have no hesitation in calling your attention to it. And for a right speaking of the sound r, gargling with sweetened water can prove very helpful. The sweet water must, however, be properly and thoroughly gargled. Particularly with children the gargling can have excellent results.

And now I want to pass on to something else that should be familiar to everyone who wants to speak properly, and which an intending actor will certainly need to master thoroughly.

I have, as you know, repeatedly pointed out that right speaking is not to be attained by physiological exercises, but that we have to learn it from the speech organism itself. We have in these lectures taken cognisance of many things that can be learned from the speech organism, and we have added to them today. We have seen that from m, b, p we learn the right cooperation of the lips, that from v, w we learn how to use rightly together lower lip and upper teeth, and from s, c, z the two rows of teeth. We have seen also how the tongue must always remain behind the teeth in l, n, d, t and lastly how we are to manipulate the root of the tongue in g, k, r, j, qu.

The sounds themselves are our teachers. It is only a matter of our knowing how to engage their help. If we have once understood this, then that will mean that all the several parts of our organism of throat and mouth have been received as pupils in the school of the sounds. The sounds are verily the Gods from whom we are to learn how to form our speaking.

But now, as I was saying, there is yet another matter to which we must give our attention. It concerns the breathing, and is the one item of guidance to be salvaged from all the tangled mass of instructions given in schools of speech training today. In speaking, we should use up, steadily and quietly, all our available breath. If, while we are speaking, we take a fresh breath before the inbreathed air we have in the lungs is exhausted, then our speaking will invariably be poor and feeble.

We are, as it were, in possession of the secret of well- formed speech when we know that good speaking depends upon the use to the full of the air that we have within us. We must accordingly accustom ourselves to the practice of exercises, once more derived from speech itself, where we have, to begin with, to take a deep full breath.

What does it imply, to take a deep full breath? It means that the diaphragm is pressed down as far as it can be without injury to health. You must be able to feel in the region of the diaphragm that the inbreathing is complete. You will, as teacher, need to lay your hand on your pupil in the region of the diaphragm in order to demonstrate to him the expansion that has to take place there, the change that must necessarily accompany a thorough inbreathing.

Then you will get your pupil to hold this inbreathed air and continue speaking with it until all the air he took in has been breathed out again. It must never happen that he stops to take breath so long as there is still any inbreathed air left in his lungs. It should indeed become for the pupil entirely a matter of instinct: never to pause for breath until the inbreathed air is exhausted.

Having first taken a deep breath and become conscious of what happens in the region of the diaphragm as he in-breathes, conscious too of the whole gradual change that takes place there until the inbreathed air is completely exhausted (for this preparatory stage the sound a can serve), the student may then proceed to the following exercise.

First a sequence of vowels, spoken slowly so that they occupy the time of a complete out-breathing. Let him say a e u, and continue with these sounds until he needs to take a fresh breath. Then the same with consonants. Let him keep on with k l s f m for the whole period of an out-breathing. This exercise, which has for its ultimate aim the full use of the in-taken breath before any more air is inbreathed, provides us also with a remedy, in fact the only right and healthy remedy, for stuttering. The reason why rhythmic exercises can prove so remarkably helpful for stuttering is that a good rhythm necessarily demands right breathing. One is obliged to breathe properly if one has to say:

‘Und es wallet and woget and brauset and zischt (take breath)

Wie wenn Wasser mit Feuer sich mengt. 6

It is quite possible to hold one's breath throughout each line; in fact, one can hardly help doing so. And that is what you will have to achieve with your stutterer. He must not take breath until the inbreathed air is used up. For his stuttering is due to the fact that an anxiety which makes him gasp for air has become in him organic. What he needs is something that can lure him away from this anxious fear that makes him strain to catch his breath; and we shall exactly meet that need if, when he has begun to stutter, we get him to sing, or to say some poetry. Fear and anxiety are connected also with anger, and you know how an angry person will often gasp for breath. Where there is stuttering, however, the anger and anxiety have become organic and we cannot expect improvement without long and steady practice of exercises.

You probably know the story of the apothecary's assistant who was inclined to stutter whenever he was worried or anxious. The apothecary was having tea in a room upstairs with some friends. The assistant burst into the room and all he could say was: Die Apo-, die Apothe-, Apothe-, Apothe- ... The k was there in his way, he couldn't get past it. The apothecary, seeing the poor fellow pale with fear, realised that it was imperative to find out what was the matter. So he said to the assistant: ‘Sing it, man!’ And the man sang quite perfectly: ‘Die Apotheke brennt!’ (The shop is on fire!) Yes, he sang the information without any difficulty. And there was not a moment to be lost; the fire was raging in the cellar quite furiously. It was the singing that did it!

Constant steady practice of exercises can have permanent results; only, the exercises have to be done with the necessary inner energy. When unconsciousness intervenes, the stuttering, since it has become organic, is liable to recur. Let me tell you of a case that I found particularly interesting. A friend of mine who was a poet suffered from a stutter. He overcame his disability to the point of being able to read aloud his own poems that were in long lines of verse. He would read rhythmically and without the least sign of difficulty; no one listening would have any suspicion that he was a stutterer. My friend was, however, a man who was easily excited and upset, and it would frequently happen that in ordinary conversation his stuttering would show itself again. (He was one who never had the patience to undertake exercises.) One day he was asked by a man, who was, to say the least, not very tactful: ‘Do you always stutter like this?' His reply was: ‘N-n-n-not unless I'm speaking to someone I just can't bear!’

A defect in speaking can thus locate itself in the organs, can become organic. In the case of lisping, we saw that there is a disability, when speaking l, n, d, t, to get tongue and upper teeth to cooperate as they should; the trouble in stuttering and stammering is that the root of the tongue is not under proper control. For it is the root of the tongue that reacts at once to disorder in the breathing A stutterer will therefore do well, as we said, to take g, k and r for his teachers — the r a little sweetened with sweet water.

In the sounds of speech live Divine Beings; and we must approach these Beings with devotion, with prayerful devotion. They will then be the very best teachers we could possibly have. All the many rules that are propounded for the management of the breath — apart from the one I have spoken of: Not until I have no air left in my lungs must I draw breath — all the others lead us astray into the sphere of the intellectual. That one rule, however, must become instinctive knowledge for the speaker. Instinctively he should go on using up the inbreathed air as long as he has any left. No other rules are needed for the gymnastics of the breath, but this one is absolutely indispensable. It has to be learned in the way I have described, and should be taught in every properly constituted school for the stage.

What I would have you understand, my dear friends, is that there are dangers attending all artistic activity, and only if we are able to bring to our own art a mood of religious devotion can we escape these dangers. The artist of the stage is especially exposed to them; they can actually assume for him the form of artistic faculties, but faculties that work with demoralising effect. Veneration, religious veneration for the sounds of speech! The words ring strange to us; but we must have courage to receive them and make them our own. For in these divine teachers of ours, in these sounds of speech, a whole world is contained. If we would become true ‘formers of the word’, we must never forget that the word was ‘in the beginning’. Despite all conflicting interpretations, that is what the opening words of the Gospel of St. John mean. ‘In the beginning was the Word’, the Wisdom-filled Word. A mood of devotion should imbue everything that has to do with the word.

But now, wherein lies the danger that threatens the actor, and no less the producer?

Actor and producer are on the stage, or behind it. This means, they are in a completely different world from the world of the auditorium. But the two worlds have to go together, they have to go absolutely hand in hand. It should never for a moment occur to us as possible that this harmonious cooperation should be lacking in any smallest detail. And yet how unlike, how essentially unlike, the two worlds are! When you are on and behind the stage, you have there a reality. This reality, when it is shown to the audience, has to be converted into an illusion. But not on the stage — nor behind it; it can't be illusion there. For the audience who are sitting down below in front, it is an illusion — mysterious, terrible, charming, delightful, perhaps even mystical. But for those who are working on or behind the stage, the illusion changes into trivial reality.

I remember how forcibly this was brought home to me once when I was working with a company and we had to stage Maeterlinck's L'Intruse. An essential feature in this little drama is the gradual approach of sounds that are at first heard only in the distance. These sounds have to make the impression of something that is full of mystery; they are in reality the harbinger of death, they are bringing death to the one who lies ill in the adjoining room. Thus they will, you see, have to be of such a nature as to awaken in the audience a thoroughly mystical and mysterious mood.

But now in order to achieve this end, you will have to make use of quite trivial devices. Somewhere in the wings you will create a noise like the sharpening of a scythe heard at a distance — a noise that is to give the first indication of something rather mystically terrifying that sounds from far away. Then a little later, you will want a noise that sounds nearer. You will perhaps arrange for a key to be turned slowly in its lock by someone who is coming into the house. Just think what trivialities you resort to! When you are thinking out contrivances of this nature, you are converting the impression you want to make on the audience into the utmost triviality.

I wanted now to provide for a still further enhancement of the mood. Behind the stage, my dear friends, we treat these things as matters of pure technique, and are delightfully indifferent to all the feelings we are hoping to arouse in the spectator who experiences the illusion. And it occurred to me that at the moment when the key had been turned in the lock and someone had entered the house, someone else might start up quickly like this (chair thrown back on to the floor). The action did, in fact, greatly intensify the illusion in the audience. Following on the mysterious sounds already described, it fairly made their hearts stand still with terror.

On the stage, a chair falling down — that was all it was in dry prose; but among the audience it produced an illusion of dithering fear.

It would, you know, be quite wrong for us to put ourselves forward as reformers and express disapproval of devices of this nature. On the contrary, we must certainly use such methods — the more of them the better! Their use requires, however, that our devotion to the spiritual be all the greater. Our hearts must be so full of devotion to the spiritual that we can endure unscathed all the trivial subterfuges that have to be undertaken behind the stage and in the wings.

The actor's inner life of feeling has to undergo change and development, until he is able to approach the whole of his art in a religious mood. Suppose a poet is writing an ode. If he is genuinely absorbed in the mood of the ode, he won't be thinking that his pen doesn't seem to be writing very smoothly. Similarly, on the stage, you should have developed such instinctive devotion to your work that even, let me say, such a simple action as knocking over a chair, you carry out with no other feeling than that you are doing a spiritual deed.

Not until this mood is attained will it be possible for the art of the stage to be filled and pervaded with the spirit that rightly belongs to it. Indeed its whole future depends upon that. And do not imagine the desired mood can be attained by any sentimental exhortations; no, only by dealing with realities. And we are dealing with realities when the sounds of speech in their mysterious runing become for us Gods — Gods who form within us our speaking. This should be the feeling that inspires all we do; it is also the determining sign of true art. It must even go so far, my dear friends, that never for a moment do we cease to be conscious of the fact that the illusion in the audience has to be created by a truth that is spiritually experienced in the souls of both actor and producer. We need to recognise this and take our guidance from it, even though we must admit that the audiences of today do not give us quite the picture that we on the stage would like to have before us.

You will, however, find that if the mood of which I have been speaking prevails on and behind the stage, it will work in imponderable ways upon the audience. The attitude of mind that one would be so glad to find there will develop more quickly under this influence than by any other method. We shall not help its development by drawing up elaborate plans or by making all kinds of promises at the inauguration of some new dramatic school or theatre. The one and only way to evoke a right attitude in the audience is to make sure that the whole of the work undertaken in connection with the stage is brought under the sway of soul and spirit.

To create the conditions for a harmonious cooperation between stage and critics is quite another matter, and infinitely harder of attainment. Many of the difficulties under which dramatic art labours today are, in fact, directly due to the utterly unnatural condition into which criticism has drifted. What goes by the name is not genuine criticism at all. Men like Kerr or Harden may be very clever, they may even found schools of criticism, but what they write and teach is built up on a purely negative principle. We must not allow ourselves to be misled and imagine that their criticisms have any sort of connection with art. They have none. These men are utterly indifferent to art, and it is important for the actor to realise that what they say has nothing whatever to do with what he, as an artist, intends and undertakes. It is, in fact, his bounden duty to change Kerr into kehr, and ‘aus-kehr-en’ the critics — ‘clear the decks’ of them, once and for all. For at the root of all this spurious criticism lies, as I said, a purely negative attitude.

I once had an interesting experience which let me into the secret of the rise of this kind of criticism. For this kind of criticism is no more than a perfectly natural outcome of a style of journalism which this experience of mine enabled me to catch as it were in the moment of its birth. Many years ago I was present at a rather large gathering of people in Berlin, among whom was Levysohn, chief editor at the time of the Berliner Tageblatt. I had some talk with him and in course of conversation we came to speak of Harden. For it cannot be denied that Harden was among the interesting figures of the early nineties of last century; he showed remarkable pluck and confidence in the way he put himself forward. True, if one looked behind the scenes, one was forced to relinquish many illusions about him. But for all that, he was a person of some note, was Harden; and in my talk with Levysohn I drew attention to some of his good points. By way of reply, Levysohn told me the following. ‘When you have a man like Harden,' he said, ‘you've got to understand him. Harden came originally from the provinces, where he had been an actor in a small way. He threw up his job and came to Berlin, hoping to make a living there. I was at that time arranging to start a Monday morning paper, to which the Berliner Tageblatt partly owes its origin. I wanted to make a really good thing of it. It was the first of its kind in Berlin, and I was determined that people should buy it up eagerly like hotcakes. A plan occurred to me which I myself thought very wily, and it is on account of this plan of mine that I claim credit for starting Harden off in the good style of writing that he has. Yes, Harden has me to thank for it. I engaged some young fellows who were hanging about, waiting for jobs, fellows who, I reckoned, had a bit of talent, though not much. You can get people to do anything if you only set about it in the right way!’ ... There you have the cynicism of a chief editor in the eighties and nineties of last century! Harden was of course one of the young men who were chosen. Levysohn told them: ‘Now look, you will get so and so many marks per month. And all you have to do is to sit all day long in a coffee house and read the papers. One of you will undertake to read all the political articles; another will study the articles dealing with art — or rather, one the articles on painting and another those on drama. Then you have only to sit down on Sunday afternoon and each one of you write an article that is different from those he has been reading all through the week.' ... This suited Harden admirably. ‘Every week,' said Levysohn, ‘he would bring me his article, and each time it was entirely different from any of the articles he had read during the week. And that is still Harden's art. There you have the secret of his Zukunft. So I, you see, am responsible,' said Levysohn in conclusion, ‘for Harden's becoming such a good journalist.'

Yes, when you look behind the scenes of this stage — for journalism is also a stage! — you are in for a bit of disillusionment there too. And it will be a harder matter to cure the reading public than to cure the public you have before you in the theatre. The cure cannot indeed ever come about until people wake up to see how slight a connection there is between a criticism that has a merely negative foundation and the ideals we are called upon to cherish for art.

Tomorrow I would like to say more on this in a wider connection and consider with you what follows for the actor and his art from his relations with the public and with the critics; and there we shall have to bring this course of lectures to a close.

1. Both lips: m b p

2. Lower lip and upper teeth: f v w

3. Upper and lower teeth: s c z

4. Tongue works behind the upper teeth: l n d t

5. Root of the tongue: g k r j qu

or, using English letters:

1. Both lips: m b p

2. Lower lip and upper teeth: f v

3. Upper and lower teeth: s (‘easy’ or ‘say’)

4. Tongue works behind upper teeth: l n d t

5. Root of the tongue: g k r (guttural) y (consonantal) kv.

Rudolf Steiner: "The sexuality which made its appearance in the Lemurian Age, when we trace it backwards, when we see it in its ever higher and higher nature, becomes the Second Logos. Through the descending Kama-Principle it was the manifestation of Jehovah; through the ascending Buddhi-Principle it was the manifestation of Christ."

Source: October 17, 1905

The conclusion to the lecture cycle Universe, Earth, and Man

Lecture 11 of 11

Rudolf Steiner, Stuttgart, August 16, 1908:

In the previous lectures wide reaches, both of human evolution and also of world evolution, were brought before our souls. We saw how mysterious connections in the evolution of the world are reflected in the civilizations of the different nations belonging to the post-Atlantean period. We saw how the first epoch of earthly development is reflected in the civilization of ancient India; the second, during which the separation of the sun from the earth took place, is reflected in the Persian civilization; and we have endeavoured, as far as time permitted, to sketch the various events of the Lemurian epoch — the third in the course of the earth's development — in which man received the foundations of his ego, which is reflected in the civilization of Egypt. It was pointed out that the initiation wisdom of ancient Egypt was a kind of remembrance of this, which was the first period of earthly evolution in which man participated. Then, coming to the fourth age, that in which the true union between body and spirit is so beautifully presented in the art of Greece, we showed it to be a reflection of what man experienced with the ancient gods, the beings we have described as Angels. Nothing remained that could be reflected in our age — the fifth — the age now running its course. Secret connections do, however, exist between the different periods of post Atlantean civilization; these we have already touched on in the first of these lectures.

You may recall how it was stated that the confinement of the people of the present day to their own immediate surroundings, that is, to the materialistic belief that reality is only to be found between life and death, can be traced to the circumstance of the Egyptians having bestowed so much care on the preservation of the bodies of the dead. They tried at that time to preserve the physical form of man, and this has not been without an effect on souls after death. When the bodily form is thus preserved the soul after death is still connected in a certain way with the form it bore during life. Thought-forms are called up in the soul, these cling to the sensible form, and when the person incarnates again and again and the soul enters into new bodies these thought-forms endure.

All that the human soul experienced when it looked down from spiritual heights upon its corpse is firmly rooted within it, hence it has not been able to unlearn this, nor to turn away from the vision which bound it to the flesh. The result has been that countless souls who were incorporated in ancient Egypt are born again with the fruits of this vision, and can only believe in the reality of the physical body. This was firmly implanted in souls at that time. Things that take place in one age of culture are by no means unconnected with the ages that follow.

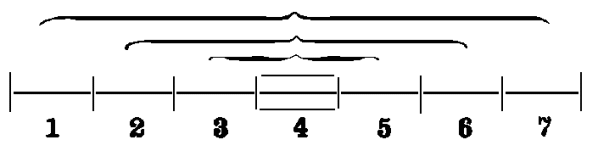

Suppose that we represent here the seven consecutive cultural periods of post-Atlantean civilization by a line. The fourth age, which is exactly in the middle, occupies an exceptional position.

We have only to consider this age exoterically to see that in it the most wonderful physical things have been produced, things by which man has conquered the physical world in a unique and harmonious way. Looking back to the Egyptian pyramids we observe a type of geometric form which demonstrates certain things symbolically. The close union of spirit — the formative human spirit — and the physical form had not yet been completed. We see this with special clearness in the Sphinx, the origin of which is to be traced to a remembrance of the Atlantean etheric human form. In its physical form the Sphinx gives us no direct conviction of this union, although it is a great human conception; in it we see the thought embodied that man is still animal-like below and only attains to what is human in the etheric head.

What confronts us on the physical plane is ennobled in the fourth age in the forms of Greek plastic art; and the moral life, the destiny of man, we find depicted in the Greek tragedies. In them we see the inner life of the spirit played out upon the physical plane in a very wonderful way; we see the meaning of earthly evolution in so far as the gods are connected with it.

So long as the earth was a part of the sun, high Sun-Spirits were united with the human race. By the end of the Atlantean epoch these exalted Beings had gradually faded, step by step, along with the sun, from the consciousness of man. Human consciousness was no longer capable of reaching up after death to the high realms where vision of the Sun-Spirits was possible. Assuming that we are at the standpoint of these Beings (which we can be in spirit), we can picture them saying: We were once united with humanity but had to withdraw from them for a time. The divine world had to disappear from human consciousness so as to re-appear in a newer, higher form through the Christ-Impulse.

A man who belonged to Grecian civilization was incapable as yet of understanding what was to come to earth through the Christ; but an Initiate, one who, as we have seen, knew the Christ aforetime, could say: That spiritual form which was preserved in men's minds as Osiris had to disappear for a time from the sight of man, the horizon of the Gods had to be darkened, but within us dwells the sure consciousness that the glory of God will appear again on earth. This certainty was the result of the cosmic consciousness which men possessed and the consciousness of the withdrawal of the glory of God and of its return is reflected in Greek tragedy.

We see man here represented as the image of the Gods, we see how he lives, strives, and has a tragic end. At the same time the tragedy holds within it the idea that man will yet conquer through his spiritual power. The drama was intended as a presentation of living and dying humanity, and at the same time it reflected man's whole relationship to the universe. In every realm of Greek culture we see this union between things of the spirit and things of the senses. It was a unique age in post-Atlantean civilization.

It is remarkable how certain phenomena of the third age are connected as by underground channels with our own, the fifth age. Certain things which were sown as seed during the Egyptian age are re-appearing in our own; others which were sown as seed during the Persian age will appear in the sixth; and things belonging to the first epoch will return in the seventh. Everything has a deep and law-filled connection, the past pointing always to the future. This connection will best be realized if we explain it by referring to the two extremes, those things connecting the first and the seventh age. Let us turn back to the first age and consider, not what history tells us, but what really existed in ancient pre-Vedic times.

Everything that appeared later had been first prepared for; this was especially the case with the division of mankind into castes. Europeans may feel strong objections to the caste system, but it was justified in the civilization of that time, and is profoundly connected with human karma. The souls coming over from Atlantis were really of very different values, and in some respects it was suitable for these souls, of whom some were at a more advanced stage than others, to be divided in accordance with the karma they had previously stored up for themselves. In that far off age humanity was not left to itself as it is now, but was really led and guided in its development in a much higher way than is generally supposed. At that time highly advanced individuals, whom we call the Rishis, understood the value of souls, and the difference there is between the various categories of souls. At the bottom of the division into castes lies a well-founded cosmic law. Though to a later age this may seem harsh, in that far-off time, when the guidance of humanity was spiritual, the caste principle was entirely suited to human nature.

It is true that in the normal evolution of man those who lived over into a new age with a particular karma came also into a particular caste, and it is also true that a man could only rise above any special caste if he underwent a process of initiation. Only when he attained a stage where he was able to strip off that which was the cause of his karma, only when he lived in Yoga, could the difference in caste, under certain circumstances, be overcome. Let us keep in mind the Anthroposophical principle which lays down that we must put aside all criticism of the facts of evolution and strive only to understand them. However had the impression this division into castes makes on us at the present time, there was every justification for it, and it has to be taken in connection with a far-reaching and just arrangement regarding the human race.

When a person speaks of races today he speaks of something that is no longer quite correct; even in Theosophical handbooks great mistakes are made on this subject. In them it is said that our evolution runs its course in Rounds, that in each Round there are Globes, and in each Globe, Races which develop one after the other — so that we have races in each epoch of the earth's evolution.

But this is not the case. Even in regard to present humanity there is no justification for speaking of a mere development of races. In the true sense of the word we can only speak of race development during the Atlantean epoch. People were so different in external physiognomy throughout the seven periods that one might speak rather of different forms than races. While it is true that the races have arisen through this, it is [in]correct to speak of races in the far back Lemurian epoch; and in our own epoch the idea of race will gradually disappear along with all the differences that are a relic of earlier times. We still speak of races, but all that remains of these today are relics of differences that existed in Atlantean times, and the idea of race has now lost its original meaning. What new idea is to arise in place of the present idea of race?

Humanity will be differentiated in the future even more than in the past; it will be divided into categories, but not in an arbitrary way; from their own spiritual inner capacities men will come to know that they must work together for the whole body corporate.

There will be categories and classes however fiercely class-war may rage today, among those who do not develop egoism but accept the spiritual life and evolve toward what is good a time will come when men will organize themselves voluntarily. They will say: One must do this, the other must do that. Division of work even to the smallest detail will take place; work will be so organized that a holder of this or that position will not find it necessary to impose his authority on others. All authority will be voluntarily recognized, so that in a small portion of humanity we shall again have divisions in the seventh age, which will recall the principle of castes, but in such a way that no one will feel forced into any caste, but each will say: I must undertake a part of the work of humanity, and leave another part to another — both will be equally recognized.

Humanity will be divided according to differences in intellect and morals; on this basis a spiritualized caste system will again appear. Led, as it were, through a secret channel, the seventh age will repeat that which arose prophetically in the first. The third, the Egyptian age, is connected in the same way with our own. Little as it may appear to a superficial view, all that was laid down during the Egyptian age re-appears in the present one. Most of the people living on the earth today were incarnated formerly in Egyptian bodies and experienced an Egyptian environment; having lived through other intermediate incarnations, they are now again on earth, and, in accordance with the laws we have indicated, they unconsciously remember what they experienced in Egypt.

All this is re-appearing now in a mysterious way, and if you are willing to recognize such secret connection of the great laws of the universe working from one civilization to another, you must make yourselves acquainted with the truth, not with all those legendary and fantastic ideas which are given out concerning the facts of human evolution.

People think too superficially about the spiritual progress of humanity. For example, someone remarks about Copernicus that a man with such ideas as his was possible, because in the age in which he lived a change in thought had arisen regarding the solar system. Anyone holding such an opinion has never studied, even exoterically, how Copernicus arrived at his ideas concerning the relationship of the heavenly bodies. One who has done this, and who more especially has followed the grand ideas of Kepler, knows differently, and he will be strengthened even more in these ideas by what occultism has to say about it.

Let us consider this so that we may see the matter clearly, and try to enter into the soul of Copernicus. This soul had lived in the age of ancient Egypt, and had then occupied an important position in the cult of Osiris; it knew that Osiris was held to be the same as the high Sun-Being.

The sun, in a spiritual sense, was at the centre of Egyptian thought and feeling; I do not mean the outwardly visible sun; it was regarded only as the bodily expression of the spiritual sun. Just as the eye is the expression for the power of sight, so to the Egyptian the Sun was the eye of Osiris, the embodiment of the Spirit of the Sun. All this had been experienced at one time by the soul of Copernicus, and it was the unconscious memory of it that impelled him to renew, in a form possible to a materialistic age, this ancient idea of Osiris, which at that time had been entirely spiritual. When humanity had sunk more deeply within the physical plane, this idea confronts us again in its materialistic form, as the Copernican theory.

The Egyptians possessed the spiritual conception and it was the world-karma of Copernicus to retain a memory of such conceptions, and this conjured forth that “combination of bearings” that led to his theory of the solar system. The case was similar with Kepler, who, in his three laws, presented the movement of the planets round the sun in a much more comprehensive way; however abstract they may appear to us, they were the result of a most profound conception. A striking fact in connection with this highly gifted being is contained in a passage written by himself and which fills us with awe when we read it. Kepler writes: “I have thought deeply upon the Solar System. It has revealed to me its secrets; I will carry over the sacred ceremonial vessels of the Egyptians into the modern world.”

Thoughts implanted in the souls of the ancient Egyptians meet us again, and our modern truths are the re-born myths of Egypt. Were it desired, we could follow this up in many details; we could follow it up to the very beginnings of humanity. Let us think once more of the Sphinx, that wondrous, enigmatic form which later became the Sphinx of Oedipus, who put its well-known riddle to man. We have learnt already that the Sphinx is built up from that human form which on the physical plane still resembled that of animals, although the etheric part had already assumed human form. In the Egyptian age man could only see the Sphinx in an etheric form after he had passed through certain stages of initiation. Then it appeared to him. But the important thing is that when a man had true clairvoyant perception it did not appear to him merely as a lump of wood does, but certain feelings were necessarily associated with the vision.

Under certain circumstances a callous person may pass by a highly important work of art and remain unmoved by it; clairvoyant consciousness is not like this; when really developed the fitting emotion is already aroused. The Greek legend of the Sphinx expresses the right feeling, experienced by the clairvoyant during the ancient Egyptian period and also in the Grecian Mysteries, when he had progressed so far that the Sphinx appeared to him. What was it that then appeared before his eyes? He beheld something incomplete something that was in course of development. The form he saw was in a certain way related to that of animals, and in the etheric head we saw what was to work within the physical form in order to shape it more like man. What man was to become, what his task was in evolution, this was the question that rose vividly before him when he saw the Sphinx — a question full of longing, of expectation, and of future development.

The Greeks say that all investigation and philosophy have originated from longing; this is also a saying of clairvoyants. A form appears to man which he can only perceive with his astral consciousness; it worries him, it propounds a riddle, the riddle of man's future. Further, this etheric form, which was present in the Atlantean epoch and lived on as a memory into the Egyptian age, is embodied more and more in man, and re-appears on the other side in the nature of man. It reappears in all the religious doubts, in the impotence of our age of civilization when faced with the question: What is man? In all unanswered questions, in all statements that revolve round “Ignorabimus,” we have to see the Sphinx. In ages that were still spiritual man could rise to heights where the Sphinx was actually before him — today it dwells within him in countless unanswered questions.

It is therefore very difficult for man at the present time to arrive at conviction with regard to the spiritual world. The Sphinx, which formerly was outside him, is now in his inner being, for a Being has appeared in the central epoch of post-Atlantean evolution Who has cast the Sphinx into the abyss — into the individual inner being of every man.

When the Greco-Latin age, with its after-effects, had continued into the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries we come to the fifth post-Atlantean age. Up to the present new doubts have arisen more and more in place of the old certainty. We meet with such things more and more, and if desired we could discover many more instances of Egyptian ideas, transformed into their materialistic counterpart in the new evolution. We might ask what has really happened in the present age, for this is no ordinary passing over of ideas; things are not met with directly, but they are as if modified. Everything is presented in a more materialistic form; even man's connection with animal nature re-appears, but changed into a materialistic conception. The fact that man knew in earlier times that he could not shape his body otherwise than in the semblance of animals, and that on this account in his Egyptian remembrances he pictured even his gods in animal forms, confronts us today in the generally held materialistic opinion that man has descended from animals. Darwinism is nothing but an heirloom of ancient Egypt in a materialistic form.

From this we see that the path of evolution has by no means been a straightforward one, but that something like a division has taken place, one branch becoming more materialistic and one more spiritual. That which had formerly progressed in one line now split into two lines of development, namely, science and belief.

Going back into earlier times, to the Egyptian, Persian, and ancient Indian civilizations, one does not find a science apart from faith. What was known regarding the spiritual origin of the world passed in a direct line to knowledge of particular things; men were able to rise from knowledge of the material world to the most exalted heights; there was no contradiction between knowledge and faith. An ancient Indian sage or a Chaldean priest would not have understood this difference; even the Egyptians knew no difference between what was simply a matter of belief or a fact of knowledge. This difference became apparent when man had sunk more deeply into matter, and had gained more material culture; but in order to gain this another organization was necessary.

Let us suppose that this descent of man into matter had not taken place; what would have happened? We considered a like descent in the last lecture, but it was of a different nature; this is a new descent in another realm, by which something like an independent science entered alongside the comprehension of what was spiritual. This occurred first in Greece. Up till then opposition between science and religion did not exist; and would have had no meaning to a priest of Egypt. Take, for instance, what Pythagoras learnt from the Egyptians, the teaching regarding numbers. This was not merely abstract mathematics to him; it gave him the musical secrets of the world in the harmony of numbers. Mathematics, which is only something abstract to the man of the present day, was to him a sacred wisdom with a religious foundation.

Man had, however, to sink more and more within the material, physical plane, and it can be seen how the spiritual wisdom of Egypt reappears — but transformed into a materialistic, mythical conception of the universe. In the future, the theories of today will be held to have had only temporal value, just as ancient theories have only a temporal value to the man of today. Perhaps men will then be so sensible that they will not fall into the mistake of some of our contemporaries who say: “Until the nineteenth century man was absolutely stupid as regards science; it was only then he became sensible all that was taught previously about anatomy was nonsense, only the last century has produced what is true.” In the future men will be wiser, and will not give tit for tat; they will not reject our myths of anatomy, philosophy, and Darwinism so disdainfully as present-day man rejects ancient truths. For it is the case that things which today are regarded as firmly established are but transitory forms of truth.

The Copernican system is but a transitory form, it has been brought about through the plunge into materialism, and will be replaced by something different. The forms of truth continually change. In order that all connection with what is spiritual should not be lost, an even stronger spiritual impulse had to enter human evolution. This was described yesterday as the Christ-Impulse. For a time mankind had to be left to itself, as it were, as regards scientific progress, and the religious side had to develop separately; it had to be saved from the progressive onslaught of science.

Thus we see how science, which devoted itself to material things, was separated for a while from things spiritual, which now followed a special course and the two movements — belief in what was spiritual, and the knowledge of external things — proceeded side by side. We even see in one particular period of development in the Middle Ages, a period immediately preceding our own, that science and belief consciously oppose each other, but still seek union.

Consider the Scholastics. They said: Faith was given to man by Christ, this we may not deny; it was a direct gift; and all the science which has been produced since the division took place, can only serve to prove this gift. We see in scholasticism the tendency to employ all science to prove revealed truth. At its prime it said: Men can gaze upwards to the blessedness of faith and to a certain degree human science can enter into it, but to do this men must devote themselves to it.

In the course of time all relationship between science and belief was, however, lost, and there was no longer any hope that they could advance side by side. The extremity of this divergence is found in the philosophy of Kant, where science and belief are completely sundered. In it, on the one hand, the categorical imperative is put forward with its practical postulates of reason; on the other hand, purely theoretical reason which has lost all connection with spiritual truths and declares that from the standpoint of science these cannot be found.

Another powerful impulse was, however, already making itself felt, which also represented a memory of ancient Egyptian thought. Minds appeared that were seeking a union between science and belief, minds that were endeavouring, through entering profoundly into science, to recognize the things of God with such certainty and clarity that they would be accessible to scientific thought. Goethe is typical of such a thinker and of such a point of view. To him religion, art, and science were one; he felt the works of Greek art to be connected with religion, as he felt the great thoughts of Divinity to be reflected in the countless plant formations he investigated.

Taking the whole of modern culture, we have to see in it a memory of Egyptian culture; Egyptian thought is reflected in it from its beginning.

The division in modern culture between science and belief did not arise without long preparation, — and if we are to understand how this came about we must glance briefly at the way post-Atlantean culture was prepared for during the Atlantean epoch.

We have seen how a handful of people who dwelt in the neighbourhood of Ireland had progressed the furthest; they had acquired those qualities which had to appear gradually in the succeeding epochs of civilization. The rudiments of the ego had been developing as we know since the Lemurian epoch, but each stage of selfhood in this small group of people, by whom the stream of culture was carried from West to East, consisted in a tendency to logical thought and the power of judgment. Up to this time these did not exist; if a thought arose it was already substantiated. The beginning of thought that was capable of judgment was implanted in these people, and they bore the rudiments of this with them from West to East in their colonizing migrations, one of which went southwards towards India. Here the first foundations of constructive thinking were laid. Later, this constructive thinking passed into the Persian civilization. In the third cultural period, that of Chaldea, it grew stronger and with the Greeks it developed so far that they have left behind them the glorious monument of Aristotelian philosophy.

Constructive thought continued to develop more and more, but always returned to a central point, where it received reinforcement. We must picture it as follows: When civilization came from the West into Asia one group, that having the smallest amount of purely logical thinking capacity, went toward India; the second group, which traveled towards Persia, had a little more; and the group that went towards Egypt had still more. From within this group were separated off the people of the Old Testament, who had exactly that combination of faculties which had to be developed in order that another forward step might be taken in this purely logical form of human cognition.

With this is associated the other thing we have been considering, namely, the descent to the physical plane. The further we descend the more does thought become merely logical, and the more it tends to a merely external faculty of judgment. Pure logical thought, mere human logic, that which proceeds from one idea to another, requires the human brain as its instrument; the cultivated brain makes logical thought possible. Hence external thinking, even when it has reached an astonishing height, can never of itself comprehend reincarnation, because it is in the first place only applicable to the things of the external sense world that surrounds us.

Logic may indeed be applied to all worlds, but can only be applied directly to the physical world; hence when it appears as human logic it is bound unconditionally to its instrument, the physical brain. Abstract thought could never have entered the world without a further descent into the world of the senses. This development of logical thought is bound up with the loss of ancient clairvoyant vision, and was bought at the cost of this loss. The task of man is to re-conquer clairvoyant vision, adding logical thought to it. In time to come he will obtain imagination as well, but logical thinking will be retained.

The human head had in the first place to be created similar to the etheric head before man could have a brain. It was then first possible for man to descend to the physical plane. In order that all spirituality should not be lost a point of time had to be chosen for the saving of this, when the last impulse to purely mechanical thought had not yet been given. If the Christ had appeared a few centuries later He would have come, as it were, too late, for humanity would have descended too far, would have been too much entangled in thought, and would not have been able to understand Christ. Christ had to come before this last impulse had been received, when the spiritually religious tendency could still be saved as a tendency leading to belief. Then came the last impulse, which plunged human thought to the lowest point, where it was banished and completely chained to physical life. This arose through the Arabs and Mohammedans. Moslem thought is a peculiar episode in Arabian life and thought, which in its passage over to Europe gave the final impulse to logical thinking — to that which is incapable of rising to what is spiritual.

To begin with, man was so led by what may be called Providence or a spiritual guidance that spiritual life was saved in Christendom; later, Arabism approached Europe from the south and provided the field for external culture. It is only capable of comprehending what is external. Do we not see this in the Arabesque, which is incapable of rising to what is living, but has to remain formal? We can also see in the Mosque how the spirit is, as it were, sucked out.

Humanity had first to be led down into matter, then in a roundabout way by means of Arabism, and the invasion of the Arab, we are shown how modern science first arose in the sharp contact of Arabism with Europeanism which had already accepted Christianity. The ancient Egyptian memories had come to life again; but what made them materialistic? What made them into thought-forms of the dead? We can show this clearly. If the path of progress had been smooth the memory of what had taken place previously would have re-appeared in our age. That which is spiritual has been saved as a whole, but one wing of European culture has been gripped by materialism. We also see how the remembrance of those who recalled the ancient Egyptian age was so changed by its passage through Arabism that it reappeared in a materialistic form. The fact that Copernicus comprehended the modern way of regarding the solar system was the outcome of his Egyptian memory. The reason why he presented it in a materialistic form, making of it a dead mechanical rotation, is because the Arabian mentality, encountering this memory from the other side, forced it into materialism.

From all that has been said you can see how secret channels connect the third and the fifth age. This can be seen even in the principle of initiation, and as modern life is to receive a principle of initiation in Rosicrucianism let us ask what this is.

In modern science we have to see a union between Egyptian remembrances and Arabism, which tends towards that which is dead. On the other side we see another union consummated, that between what Egyptian initiates imparted to their pupils and things spiritual. We see a union between wisdom and that which had been rescued as the truths of belief. This wondrous harmony between the Egyptian remembrance in wisdom and the Christian impulse of power is found in Rosicrucian spiritual teaching. So the ancient seed laid down in the Egyptian period re-appears, not merely as a repetition, but differentiated and upon a higher level.

These are thoughts which should not only instruct with regard to the universe, earth, and man, but they should enter as well into our feeling and our impulses of will and give us wings; for they show us the path we have to travel. They point the path to that which is spiritual, and also show how we may carry over into the future what, in a good sense, we have gained here on the purely material plane.

We have seen how paths separate and again unite; the time will come when not the remembrances only of Egypt will unite with spiritual truths to produce a Rosicrucian science, but science and Rosicrucianism will also unite. Rosicrucianism is both a religion and at the same time a science that is firmly bound to what is material. When we turn to the Babylonian period we find this is shown in myth of the third period of civilization; here we are told of the God Maradu, who meets with the evil principle, the serpent of the Old Testament, and splits his head in two, so that in a certain sense the earlier adversary is divided into two parts. This was in fact what actually happened; a partition of that which arose in the primeval, watery earth-substance, as symbolized by the serpent. In the upper part we have to see the truths upheld by faith, in the lower the purely material acceptance of the world. These two must be united — science and that which is spiritual — and they will be united in the future. This will come to pass when, through Rosicrucian wisdom, spirituality is intensified, and itself becomes a science, when it once more coincides with the investigations made by science. Then a mighty harmonious unity will again arise; the various currents of civilization will unite and flow together through the channels of humanity. Do we not see in recent times how this unity is being striven for?

When we consider the ancient Egyptian mysteries we see that religion, science, and art were then one. The course of the world evolution is shown in the descent of the Gods into matter; this is presented to us in a grand dramatic symbolism. Anyone who can appreciate this symbolism has science before him, for he sees there vividly portrayed the descent of man and his entrance into the world. He is also confronted with something else, namely, art, for the picture presented to him is an artistic reflection of science. But he does not see only these two, science and art, in the mysteries of ancient Egypt; they are for him at the same time religion, for what is presented to him pictorially is filled with religious feeling.

These three were later divided; religion, science, and art went separate ways, but already in our age men feel that they must again come together.

What else was the great effort of Richard Wagner than a spiritual striving, a mighty longing towards a cultural impulse? The Egyptians saw visible pictures because the external eye had need of them. In our age what they saw will be repeated; once more the separate streams of culture will unite, a whole will be constructed, this time preferably in a work of art whose elements will be the sequence of sound. On every side we find connections between what appertained to Egypt and modern times; everywhere this reflection can be seen. As time goes on our souls will realize more and more that each age is not merely a repetition but an ascent; that a progressive development is taking place in humanity. Then the most intimate strivings of humanity — the striving for initiation — must find fulfillment.

The principle of initiation suited to the first age cannot be the principle of initiation for the changed humanity of today. It is of no value to us to be told that the Egyptians had already found primeval wisdom and truth in ancient times; that these are contained in the old Oriental religions and philosophies, and that everything that has appeared since exists only to enable us to experience the same over again if we are to rise to the highest initiation. No! This is useless talk. Each age has need of its own particular force within the depths of the human soul.

When it is asserted in certain Theosophical quarters that there is a western initiation for our stage of civilization, but that it is a late product, that true initiation comes only from the East, we must answer that this cannot be determined without knowing something further. The matter must be gone into more deeply than is usually done. There may be some who say that in Buddha the highest summit was reached, that Christ has brought nothing new since Buddha; but only in that which meets us positively can we recognize what really is the question here. If we ask those who stand on the ground of Western initiation whether they deny anything in Eastern initiation, whether they make any different statements regarding Buddha than those in the East, they answer, “No.” They value all; they agree with all; but they understand progressive development. They can be distinguished from those who deny the Western principle of initiation by the fact that they know how to accept what Orientalism has to give, and in addition they know the advanced forms which the course of time has made necessary. They deny nothing in the realm of Eastern initiation.

Take a description of Buddha by one who accepts the standpoint of Western esotericism. This will not differ from that of a follower of Eastern esotericism; but the man with the Western standpoint holds that in Christ there is something which goes beyond Buddha. The Eastern standpoint does not allow this. If it is said that Buddha is greater than Christ that does not decide anything, for this depends on something positive. Here the Western standpoint is the same as the Eastern. The West does not deny what the East says, but it asserts something further.

The life of Buddha is not rightly understood when we read that Buddha perished through the enjoyment of too much pork; this must not be taken literally. It is rightly objected from the standpoint of Christian esotericism that people who understand something trivial from this understand nothing about it at all; this is only an image, and shows the position in which Buddha stood to his contemporaries. He had imparted too many of' the sacred Brahmanical secrets to the outer world. He was ruined through having given out that which was hidden, as is everyone else who imparts what is hidden.

This is what is expressed in this peculiar symbol. Allow me to emphasize strongly that we disagree in no way with Oriental conceptions, but people must understand the esotericism of such things. If it is said that this is of little importance: it is not the case. They might as well think it of little importance when we are told that the writer of the Apocalypse wrote it amid thunder and lightning, and if anyone found occasion to mock at the Apocalypse because of this we should reply: “What a pity he does not know what it means when we are told that the Apocalypse was imparted to the earth 'mid lightning and thunder!”

We must keep in mind the fact that no negation has passed the lips of Western esotericists, and that much that was puzzling at the beginning of the Anthroposophical movement has been explained by them. The followers of Western esotericism never find in it anything out of harmony with the mighty truths given to the world by H. P. Blavatsky. When we are told, for example, that we have to distinguish in the Buddha the Dhyani-Buddha, the Adi-Buddha, and the human Buddha, this is first fully explained by the Western esotericist. For we know that what is regarded as the Dhyani-Buddha is nothing but the etheric body of the historic Buddha that had been taken possession of by a God; that this etheric body had been laid hold of by the being whom we call Wotan. This was already contained in Eastern esotericism, but was only first understood in the right way through Western esotericism.

The Anthroposophical movement should be especially careful that the feeling which rises in our souls from such thoughts as these should stimulate in us the desire for further development, that we should not stand still for a moment. The value of our movement does not consist in the ancient dogmas it contains (if these are but fifteen years old), but in comprehending its true purpose, which is the opening up of fresh springs of spiritual knowledge. It will then become a living movement and will help to bring about that future which, if only very briefly, has been presented to your mental sight today, by drawing upon what we are able to observe of the past.

We are not concerned with the imparting of theoretic truths, but that our feeling, our perception, and our actions may be full of power.

We have considered the evolution of Universe, Earth, and Man; we desire so to grasp what we have gathered from these studies that we may be ready at any time to enter upon development.

What we call “future” must always be rooted in the past; knowledge has no value if not changed into motive power for the future. The purpose for the future must be in accordance with the knowledge of the past, but this knowledge is of little value unless changed into propelling force for the future.

What we have heard has presented to us a picture of' such mighty motive powers that not only our will and our enthusiasm have been stimulated, but our feelings of joy and of security in life have also been deeply moved. When we note the interplay of so many currents we are constrained to say: Many are the seeds within the womb of Time. Through an ever deepening knowledge man must learn how better to foster all these seeds. Knowledge in order to work, in order to gain certainty in life, must be the feeling that pervades all Anthroposophical study.

In conclusion I would like to point out that the so-called theories of Spiritual Science only attain final truth when they are changed into something living — into impulses of feeling and of certainty as regards life; so that our studies may not merely be theoretical, but may play a real part in evolution.

Source: August 16, 1908 GA 105