"Spirit Triumphant! Flame through the impotence of fettered, faltering souls! Burn up selfishness, kindle compassion, so that selflessness, the lifestream of humanity, may flow as the wellspring of spiritual rebirth!" — Rudolf Steiner

Saturday, November 30, 2019

The New Yoga : The Yoga of Light

Then spake Jesus again unto them, saying, I am the light of the world: he that followeth me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life. —John 8:12

John 3:11-21

Verily, verily, I say unto thee, We speak that we do know, and testify that we have seen; and ye receive not our witness.

If I have told you earthly things, and ye believe not, how shall ye believe, if I tell you of heavenly things?

And no man hath ascended up to heaven, but he that came down from heaven, even the Son of man which is in heaven.

And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up:

That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life.

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved.

He that believeth on him is not condemned: but he that believeth not is condemned already, because he hath not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God.

And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil.

For every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved.

But he that doeth truth cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest, that they are wrought in God.

"The Ancient Yoga Culture and the New Yoga Will. The Michael Culture of the Future"

Lecture 6 of The Mission of the Archangel Michael

Lecture 6 of The Mission of the Archangel Michael

Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland

November 30, 1919 — 100 years ago today

November 30, 1919 — 100 years ago today

Now, if we speak spiritual-scientifically about the human being by differentiating between head man and the rest of man, then these two organizations are, at the outset, pictures for us, pictures created by nature herself for the soul element, for the spiritual element, whose expression and manifestation they are. Man is placed in the whole evolution of earth humanity in a way which becomes comprehensible only if one considers how different is the position of the head organization in this evolution from that of the rest of the human organization. Everything connected with the head organization, which chiefly manifests as man's life of thought, is something that reaches far back in the post-Atlantean evolution of mankind. When we focus our attention upon the time which followed immediately after the great Atlantean catastrophe, that is, the time of the sixth, seventh, eighth millennium before the Christian era, we shall find a soul mood holding sway in the regions of the civilized world of that period which can hardly be compared with our soul mood. The consciousness and whole conception of the world of the human being of that time can scarcely be compared with that which characterizes our sense perception and conceptual view of the world. In my Occult Science, an Outline I have called this culture which reaches back into such ancient times, the primeval Indian culture. We may say: the human head organism of that time was different from our present head organism to a great degree and the reckoning with space and time was not characteristic of this ancient people as it is of us. In surveying the world, they experienced a survey of immeasurable spatial distances, and they had a simultaneous experience of the various moments of time. The strong emphasis on space and time in world conception was not present in that ancient period.

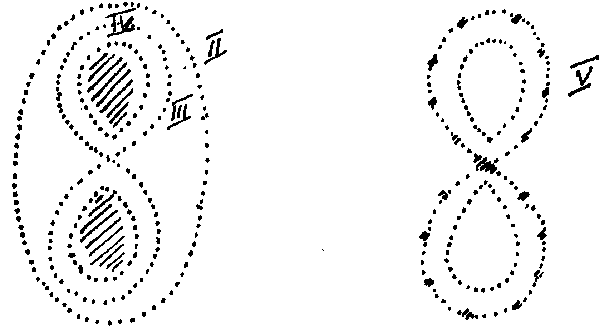

The first indications of this we find toward the fifth and fourth millennium in the period we designate the primeval Persian period. But even then the whole mood of soul life is such that it can hardly be compared with the soul and world mood of the human being of our age. In that ancient time, the main concern of the human being is to interpret the things of the world as various shades of light, brilliancy, and darkness, obscurity. The abstractions in which we live today are completely foreign to that ancient earth population. There still exists a universal, all-embracing perception, a consciousness of the permeation of everything perceptible with light and its adumbration, shading, with various degrees of darkness. This was also the way the moral world order was conceived of. A human being who was benevolent and kind was experienced as a light, bright human being, one who was distrustful and selfish was experienced as a dark man. Man's moral individuality was, as it were, aurically perceived around him. And if we had talked to a man of this ancient, primeval Persian time about that which we call today the order of nature, he would not have understood a word of it. An order of nature in our sense did not exist in his world of light and shadow. For him, the world was a world of light and shadow; and in the world of tones, certain timbres of sounding he designated as light, bright, and certain other timbres of sounding he designated as dark, shadowy. And that which thus expressed itself through this element of light and darkness constituted for him the spiritual as well as the nature powers. For him, there existed no difference between spiritual and natural powers. Our present-day distinction between natural necessity and human freedom would have appeared to him as mere folly, for this duality of human arbitrary will and the necessity of nature did not exist for him. Everything was to be included for him in one spiritual — physical unity. If I were to give you a pictorial interpretation of the character of this primeval-Persian world conception, I would have to draw the following line. (It will receive its full meaning only through that which will follow.)

|

Then after this soul mood of man had held sway for somewhat more than two thousand years, there appeared a soul mood, the echoes of which we can still perceive in the Chaldean, in the Egyptian world conception, and in a special form in the world conception whose reflection is preserved for us in the Old Testament. There something appears which is closer to our own world conception. There the first inkling of a certain necessity of nature enters human thoughts. But this necessity of nature is still far removed from that which we call today the mechanical or even the vital order of nature; at that time, natural events are conceived of as identical with Divine willing, with Providence. Providence and nature events are still one. Man knew that if he moved his hand it was the Divine within him, permeating him, that moved his hand, that moved his arm. When a tree was shaken by the wind, the perception of the shaking tree was no different for him from the perception of the moving arm. He saw the same divine power, as Providence, in his own movements and in the movements of the tree. But a distinction was made between the God without and the God within; he was, however, conceived of as unitary, the God in nature, the God in man; he was the same. And it was clear to human beings of that time that there is something in man whereby Providence that is outside in nature and Providence that is inside in man meet one another.

At that time, man's process of breathing was sensed in this way. People said: If a tree is shaking, this is the God outside, and if I move my arm, it is the God inside; if I inhale the air, work it over within me, and again exhale it, then it is the God from outside who enters me and again leaves me. Thus the same divine element was sensed as being outside and inside, but simultaneously, in one point, outside and inside; people said to themselves: By being a breathing being, I am a being of nature outside and at the same time I am myself.

If I am to characterize the world conception of the third culture period by a line, as I have done for the primeval Persian world conception by the line of the preceding drawing, I shall have to characterize it through the following line:

|

This line represents, on the one hand, the existence of nature outside, on the other hand, human existence, crossing over into the other at the one point, in the breathing process.

Matters become different in the fourth age, in the Graeco-Latin age. Here the human being is abruptly confronted by the contrast outside-inside, of nature existence and human existence. Man begins to feel the contrast between himself and nature. And if I am again to draw characteristically how man begins to feel in the Greek age, I will have to draw it this way: on the one hand he senses the external and on the other the internal; between the two there is no longer the crossing point.

|

What man has in common with nature remains outside his consciousness. It falls away from consciousness. In Indian Yoga an attempt is made to bring it into consciousness again. Therefore Indian Yoga culture is an atavistic returning to previous evolutionary stages of mankind, because an attempt is made again to bring into consciousness the process of breathing, which in the third age was felt in a natural way as that in which one existed outside and inside simultaneously. The fourth age begins in the eighth pre-Christian century. At that time the late-Indian Yoga exercises were developed which tried to call back, atavistically, that which mankind had possessed at earlier times, quite particularly in the Indian culture, but which had been lost.

Thus, this consciousness of the breathing process was lost. And if one asks: Why did Indian Yoga culture try to call it back, what did it believe it would gain thereby? one has to answer: What was intended to be gained thereby was a real understanding of the outer world. For through the fact that the breathing process was understood in the third cultural age, something was understood within man that at the same time was something external.

This must again be attained; on another path, however. We live still under the after-effects of the culture in which a twofold element is present in the human soul mood, for the fourth period ends only around the year 1413, really only about the middle of the fifteenth century. We have, through our head organization, an incomplete nature conception, that which we call the external world; and we have through our inner organization, through the organization of the rest of man, an incomplete knowledge of ourselves.

|

That in which we could perceive a process of the world and at the same time a process of ourselves is eliminated; it does not exist for us.

It is now a question of consciously regaining that which has been lost. That means, we have to acquire the ability of taking hold of something that is in our inner being, that belongs to the outer and the inner world simultaneously, and which reaches into both.

This must be the endeavor of the fifth post-Atlantean period; namely, the endeavor to find something in the human inner life in which an outer process takes place at the same time.

|

You will remember that I have pointed to this important fact; I have pointed to it in my last article in Soziale Zukunft (The Social Future) {Soziale Zukunft, Vol. III: Geistesleben, Rechtsordnung, Wirtschaft (Spiritual Life, Rights order, Economy), Vol. IV: Dreigliederung und soziales Vertrauen (The Threefold Social Order and Social Confidence), where I seemingly dealt with these things in their importance for social life, but where I clearly pointed to the very necessity of finding something which the human being lays hold of within himself and which he, at the same time, recognizes as a process of the world. We as modern human beings cannot attain this by going back to Yoga culture; that has passed. For the breathing process itself has changed. This, of course, you cannot prove clinically; but the breathing process has become a different one since the third post-Atlantean cultural period. Roughly speaking, we might say: In the third post-soul; today he breathes air. Not only our thoughts have become materialistic; reality itself has lost its soul.

I beg you, my dear friends, not to see something negligible in what I am now saying. For just consider what it means that reality itself, in which mankind lives, has been transformed so that the air we breathe is something different from what it was four millennia ago. Not only the consciousness of mankind has changed, oh no! there was soul in the atmosphere of the earth. The air was the soul. This is it no longer today, or, rather, it is soul in a different way. The spiritual beings of elemental nature of whom I have spoken yesterday, they penetrate into you, they can be breathed if one practices Yoga breathing today. But that which was attainable in normal breathing three millennia ago cannot be brought back artificially. That it may be brought back is the great illusion of the Orientals. What I am stating here describes a reality. The ensouling of the air which belongs to the human being no longer exists. And therefore the beings of whom I spoke yesterday — I should like to call them the anti-Michaelic beings — are able to penetrate into the air and, through the air, into the human being, and in this way they enter into mankind, as I have described it yesterday. We are only able to drive them away if we put in the place of Yoga that which is the right thing for today. We must strive for this. We can only strive for that which is the right thing for today if we become conscious of a much more subtle relation of man to the external world, so that in regard to our ether body something takes place which must enter our consciousness more and more, similar to the breathing process. In the breathing process, we inhale fresh oxygen and exhale unusable carbon. A similar process takes place in all our sense perceptions. Just think, my dear friends, that you see something — let us take a radical case — suppose you see a flame. There a process takes place that may be compared with inhalation, only it is much finer. If you then close your eyes — and you can make similar experiments with every one of your senses — you have the after-image of the flame which gradually changes — dies down, as Goethe said. Apart from the purely physical aspect, the human ether body is essentially engaged in this process of reception of the light impression and its eventual dying down. Something very significant is contained in this process: it contains the soul element which, three millennia ago, was breathed in and out with the air. And we must learn to realize the sense process, permeated by the soul element in a similar way we have realized the breathing process three millennia ago.

You see, my dear friends, this is connected with the fact that man, three millennia ago, lived in a night culture. Yahve revealed himself through his prophets out of the dreams of the night. But we must endeavor to receive in our intimate intercourse with the world not merely sense perceptions, but also the spiritual element. It must become a certainty for us that with every ray of light, with every tone, with every sensation of heat and its dying down we enter into a soul-intercourse with the world, and this soul-intercourse must become significant for us. We can help ourselves to bring this about.

I have described to you the occurrence of the Mystery of Golgotha in the fourth post-Atlantean period which, if we wish to be accurate, begins with the year 747 B.C. and ends with the year 1413 A.D. The Mystery of Golgotha occurred in the first third of this period, and it was comprehended at the outset, with the remnants of the ancient mode of thought and culture. This ancient way of comprehending the Mystery of Golgotha is exhausted and a new way of comprehension must take its place. The ancient way does no longer suffice, and many attempts that have been made to enable human thinking to grasp the Mystery of Golgotha have proved unsuitable to reach up to it.

You see, dear friends, all external-material things have their spiritual-soul aspect, and all things that appear in the spiritual-soul sphere have their external-material aspect. The fact that the air of the earth has become soul-void, making it impossible for man to breathe the originally ensouled air, had a significant spiritual effect in the evolution of mankind. For through being able to breathe in the soul to which he was originally related, as is stated at the beginning of the Old Testament: “And God breathed into man the breath as living soul,” man had the possibility of becoming conscious of the pre-existence of the soul, of the existence of the soul before it had descended into the physical body through birth or through conception. To the degree the breathing process ceased to be ensouled the human being lost the consciousness of the pre-existence of the soul. Even at the time of Aristotle in the fourth post-Atlantean period it was no longer possible to understand, with the human power of comprehension, the pre-existence of the soul. It was utterly impossible.

We are faced with the strange historical fact that the greatest event, the Christ Event, breaks in upon the evolution of the earth, yet mankind must first become mature in order to comprehend it. At the outset, it is still capable of catching the rays of the Mystery of Golgotha with the remnants of the power of comprehension originating in primeval culture. But this power of comprehension is gradually lost, and dogmatism moves further and further away from an understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha. The Church forbids the belief in the pre-existence of the soul — not because pre-existence is incompatible with the Mystery of Golgotha, but because the human power of comprehension ceased to experience the consciousness of pre-existence as a force, the air having become soul-void. Pre-existence vanishes from head-consciousness. When our sense processes will become ensouled again, we shall have established a crossing point, and in this crossing point we shall take hold of the human will that streams up, out of the third stratum of consciousness, as I have described it to you recently. Then we shall, at the same time, have the subjective-objective element for which Goethe was longing so very much. We shall have the possibility of grasping, in a sensitive way, the peculiar nature of the sense process of man in its relation to the outer world. Man's conceptions are very coarse and clumsy, indeed, which maintain that the outer world merely acts upon us and we, in turn, merely react upon it. In reality, there takes place a soul process from the outside toward the inside, which is taken hold of by the deeply subconscious, inner soul process, so that the two processes overlap. From outside, cosmic thoughts work into us, from inside, humanity's will works outward. Humanity's will and cosmic thought cross in this crossing point, just as the objective and the subjective element once crossed in the breath. We must learn to feel how our will works through our eyes and how the activity of the senses delicately mingles with the passivity, bringing about the crossing of cosmic thoughts and humanity's will. We must develop this new Yoga will. Then something will be imparted to us that of like nature to that which was imparted to human beings in the breathing process three millennia ago. Our comprehension must become much more soul-like, much more spiritual.

Goethe's world conception strove in this direction. Goethe endeavored to recognize the pure phenomenon, which he called the primal phenomenon, by arranging the phenomena which work upon man in the external world, without the interference of the Luciferic thought which stems from the head of man himself; this thought was only to serve in the arranging of the phenomena. Goethe did not strive for the law of nature, but for the primal phenomenon; this is what is significant with him. If, however, we arrive at this pure phenomenon, this primal phenomenon, we have something in the outer world which makes it possible for us to sense the unfolding of our will in the perception of the outer world, and then we shall lift ourselves to something objective-subjective, as it still was contained, for instance, in the ancient Hebrew doctrine. We must learn not merely to speak of the contrast between the material and the spiritual, but we must recognize the interplay of the material and the spiritual in a unity precisely in sense perception. If we no longer look at nature merely materially and, further, if we do not “think into it” a soul element, as Gustave Theodore Fechner did, then something will arise which will signify for us what the Yahve culture signified for mankind three millennia ago. If we learn, in nature, to receive the soul element together with sense perception, then we shall have the Christ relationship to outer nature. This Christ relationship to outer nature will be something like a kind of spiritual breathing process.

We shall be aided by realizing more and more, with our sound common sense, that pre-existence lies at the basis of our soul existence. We must supplement the purely egotistical conception of post-existence, which springs merely from our longing to exist after death, by the knowledge of the pre-existence of the soul. We must again rise to the conception of the real eternity of the soul. This is what may be called Michael culture. If we move through the world with the consciousness that with every look we direct outward, with every tone we hear, something spiritual, something of the nature of the soul element stream out into the world, we have gained the consciousness which mankind needs for the future.

I return once more to the image: You see a flame. You shut your eyes and have the after-image which ebbs away. Is that merely a subjective process? Yes, says the modern physiologist. But this is not true. In the cosmic ether this signifies an objective process, just as in the air the presence of carbonic acid which you exhale signifies an objective process. You are dealing here with the objective element; you have the possibility of knowing that something which takes place within you is at the same time a delicate cosmic process, if you become but conscious of it. If I look at a flame, close my eyes, let it ebb away — it will ebb away even though I keep my eyes open, only then I will not notice it — then I experience a process which does not merely take place within me, but which takes place in the world. But this is not only the case in regard to the flame, if I confront a human being and say: this man has said this or that, which may be true or untrue, this then constitutes a judgment, a moral or intellectual act of my inner nature. This ebbs away like a flame. If I confront a human being and say: this man has said this or that, which may be true or untrue, this then constitutes a judgment, a moral or intellectual act of my inner nature. This ebbs away like the flame. It is an objective world process. If you think something good about your fellow-man: it ebbs away and is an objective process in the cosmic ether; if you think something evil: it ebbs away as an objective process. You are unable to conceal your perceptions and judgments about the world. You seemingly carry them on in your own being, but they are at the same time an objective world process. Just as people of the third period were conscious of the fact that the breathing process is a process that takes place simultaneously within man and in the objective world, so mankind must become aware in the future that the soul element of which I spoke is at the same time an objective world process.

This transformation of consciousness demands greater strength of soul than is ordinarily developed by the human being of today. To permeate oneself with this consciousness means to permit the Michael culture to enter. Just as it was self-evident for the man of the second and third pre-Christian millennium to think of the air as ensouled — so must it become self-evident for us to think of light as ensouled; we must arouse this ability in us when we consider light the general representative of sense perception We must thoroughly do away with the habit of seeing in light that which our materialistic age is accustomed to see in it. We must entirely cease to believe that merely those vibrations emanate from the sun of which, out of the modern consciousness, physics and people in general speak. We must become clear about the fact that the soul element penetrates through cosmic space upon the pinions of light; and we must realize, at the same time, that this was not the case in the period preceding our age. That which approaches mankind today through light approached mankind of that former period through the air. You see here an objective difference in the earth process. Expressing this in a comprehensive concept, we may say, Air-soul-process, Light-soul-process. This is what may be observed in the evolution of the earth. The Mystery of Golgotha signifies the transition from the one period to the other.

|

My dear friends, it does not suffice, for the present age nor for the future age of mankind, to speak in abstractions about the spiritual, to fall into some sort of nebulous pantheism; on the contrary, we must begin to recognize that that which today is sensed as a merely material process is permeated by soul.

It is a question of learning to say the following: there was a time prior to the Mystery of Golgotha when the earth had an atmosphere which contained the soul element that belongs to the soul of man. Today, the earth has an atmosphere which is devoid of this soul element. The same soul element that was previously in the air has now entered the light which embraces us from morning to evening. This was made possible through the fact that the Christ has united Himself with the earth. Thus, also from the soul-spiritual aspect, air and light underwent a change in the course of the Earth evolution.

My dear friends, it is a childish presentation that describes air and light in the same manner, purely materially, throughout the millennia in which Earth evolution unfolded. Air and light have changed inwardly. We live in an atmosphere and in a light sphere that are different from those in which our souls lived in previous earthly incarnations. To learn to recognize the externally-material as a soul-spirited element: this is what matters. If we describe purely material existence in the customary manner and then add, as a kind of decoration: this material existence contains everywhere the spiritual! This will not produce genuine spiritual science. My dear friends, people are very strange in this respect; they are intent on withdrawing to the abstract. But what is necessary is the following: in the future we must cease to differentiate abstractly between the material and the spiritual, but we must look for the spiritual in the material itself and describe it as such; and we must recognize in the spiritual the transition into the material and its mode of action in the material. Only if we have attained this shall we be able to gain a true knowledge of man himself. “Blood is quite a special fluid,” but the fluid physiology speaks about today is not a “special fluid,” it is merely a fluid whose chemical composition one attempts to analyze in the same way any other substance is analyzed; it is nothing special. But if we have gained the starting point of being able to understand the metamorphosis of air and light from the soul aspect, we shall gradually advance to the soul-spiritual comprehension of the human being himself, in every respect; then we shall not have abstract matter and abstract spirit, but spirit, soul, and body working into one another. This will be Michael-culture.

This is what our time demands. This is what ought to be grasped with all the fibers of the soul life by those human beings who wish to understand the present time. Whenever something out of the ordinary had to be introduced into human world conception it met with resistance. I have often quoted the following neat example: In 1837 (not even a century ago), the learned Medical College of Bavaria was asked, when the construction of the first railroad from Fuerth to Nuremberg was proposed, whether it was hygienically safe to build such a railroad. The Medical College answered (I am not telling a fairy tale, the documents concerning it exist): Such a railroad should not be built, for people who would use such a means of transportation would become nervously ill. And they added: Should there be such people who insist on such railroads, then, it is absolutely necessary to erect, on the right and left side of the tracks, high plank walls to prevent the people whom the train passes from getting concussion of the brain. Here you see, my dear friends, such a judgment is one thing; quite another is the course which the evolution of mankind takes. Today we smile about such a document as that of the Bavarian Medical College of 1837; but we are not altogether justified in smiling; for, if something similar occurs today, we behave in quite the same manner. And, after all, the Bavarian Medical College was not entirely wrong. It we compare the state of nerves of modern mankind with that of mankind two centuries ago, then we must say that people have become nervous. Perhaps the Medical College has exaggerated the matter a bit, but people did become nervous. Now, in regard to the evolution of mankind it is imperative that certain impulses which try to enter Earth evolution really should enter and not be rejected. That which from time to time wishes to enter human cultural development is often very inconvenient for people, it does not agree with their indolence, and what is duty in regard to human cultural development must be recognized by learning to read the objective facts, and must not be derived from human indolence, not even from a refined kind of indolence. I am concluding today's lecture with these words because there is no doubt that a strongly increasing battle will take place between anthroposophical cognition and the various creeds. We can see the signs for this on all sides. The creeds who wish to remain in the old beaten tracks, who do not wish to arouse themselves to a new knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha, will reinforce their strong fighting position which they already have taken up, and it would be very frivolous, my dear friends, if we would remain unconscious of the fact that this battle has started.

I myself, you can be sure, am not at all eager for such a battle, particularly not for a battle with the Roman Catholic Church which, it seems, is forced upon us from the other side with such violence. He who, after all, thoroughly knows the deeper historical impulses of the creeds of our time will be very unwilling to fight time-honored institutions. But if the battle is forced upon us, it is not to be avoided! And the clergy of our day is not in the least inclined to open its doors to that which has to enter: the spiritual-scientific world conception. Remember the grotesque quotations I read to you recently where it was said that people should inform themselves about anthroposophically-oriented spiritual science through the writings of my opponents, since Roman-Catholics are forbidden by the Pope to read my own writings. This is not a light matter, my dear friends; it is a very serious matter! A battle which arises in such a manner, which is capable of disseminating such a judgment in the world, such a battle is not to be taken lightly. And what is more; it is not to be taken lightly since we do not enter it willingly. Let us take the example of the Roman-Catholic Church, my dear friends; matters are not different in regard to the Protestant Church, but the Roman-Catholic church is more powerful — and we have to consider time-honored institutions: if one understands the significance of the vestments of the priest when he reads the Holy Mass, the meaning of every single piece of his priestly garments, if one understands every single act of the Holy Mass, then one knows that they are sacred, time-honored establishments; they are establishments more ancient than Christianity for the Holy Mass is a ritual of the ancient Mystery culture, transformed in the Christian sense. And modern clergy who uses such weapons as described above lives in these rituals! Thus, if one has, on the one hand, the deepest veneration for the existing rituals and symbolism, and sees, on the other hand, how insufficient is the defense of and how serious are the attacks against that which wishes to enter mankind's evolution, then one becomes aware of the earnestness that is necessary in taking a stand in these matters. It is truly something worth deep study and consideration. What is thus heralded from that side is only at its beginnings; and it is not right to sleep in regard to it; on the contrary, we have to sharpen our perception for it. During the two decades in which the Anthroposophical Movement has been fostered in Middle Europe, we could indulge in sectarian somnolence which was so hard to combat in our own ranks and which still today sits so deeply embedded in the souls of the human beings who have entered the Anthroposophical Movement. But the time has passed in which we might have been allowed to indulge in sectarian somnolence. That which I have often emphasized here is deeply true, namely, that it is necessary that we should grasp the world-historical significance of the Anthroposophical Movement and overlook trifles, but that we should also consider the small impulses as serious and great.

The Ways of Anthroposophy: The Yoga of the Holy Spirit

Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland, September 30, 1920:

Yesterday's considerations led us to conclude that at one boundary of cognition we must come to a halt within phenomena and then permeate them with what the phenomena call forth within our consciousness, with concepts, ideas, and so forth. It became apparent that the realm in which these ideas are most pure and pellucid is that of mathematics and analytical mechanics. Our considerations then climaxed in showing how reflection reveals that everything present in the soul as mathematics, as analytical mechanics, actually rests upon Inspiration. Then we were able to indicate how the impulses proceeding from Inspiration are diffused throughout the ancient Indian Vedanta: the same spirit from which we now draw only mathematics and analytical mechanics was once the source of the delicate spirituality of the Vedanta. We were able to show how Goethe, in establishing his mode of phenomenology, always strives to find the archetypal phenomenon while remaining within the phenomena themselves and that his search for the archetypal phenomenon that underlies complex phenomena is, inwardly, the same as the mathematician's search for the axiom underlying complex mathematical constructs. Goethe, therefore, who himself admitted that he had no conventional mathematical training, nevertheless sensed the essence of mathematics so clearly that he demanded a method for the determination of archetypal phenomena rigorous enough to satisfy a mathematician. It is just this that the Western mind finds so attractive in the Vedanta: that in its inner organization, in its progression from one contemplation to the next, it reveals the same inner necessity as mathematics and analytical mechanics. That such connections are not uncovered by academic studies of the Vedanta is simply a consequence of there being so few people today with a universal education. Those who engage in pursuits that then lead them into Oriental philosophy have too little comprehension — and, as I have said, Goethe did have this — of the true inner structure of mathematics. They thus never grasp this philosophy's vital nerve. At the one pole, then, the pole of matter, we have been able to indicate the attitude we must assume initially if we do not wish to continue weaving a Penelope's web like the worldview woven by recent science but rather to come to grips with something that rests upon a firm foundation, that bears its center of gravity within itself.

On the other side there stands, as I indicated yesterday, the pole of consciousness. If we attempt to investigate the content of consciousness merely by brooding our way into our souls in the nebulous manner of certain mystics, what we attain are actually nothing but certain reminiscences that have been stored up in our consciousness since birth, since our childhood. This can easily be demonstrated empirically. One need think only of a certain man well educated in the natural sciences who, in order to demonstrate that the so-called “inner life” partakes of the nature of reminiscences, describes an experience he once had while standing in front of a bookstore. In the store he saw a book that captured his attention by its title. It dealt with the lower form of animal life. And, seeing this book, he had to smile. Now imagine how astonished he was: a serious scientist, a professor, who sees a book title in a bookstore — a book on the lower animals, at that! — and feels compelled to smile! Then he began to ponder just whence this smile might have come. At first he could think of nothing. And then it occurred to him: I shall close my eyes. And as he closed his eyes and it became dark all around him, he heard in the distance a musical motif. Hearing this musical motif in the moment reminded him of the music he had heard as a young lad when he danced for the first time. And he realized that of course there lived in his subconscious not only this musical motif but also a bit of the partner with whom he had hopped about. He realized how something that his normal consciousness had long since forgotten, something that had not made so strong an impression on him that he would have thought it possible for it to remain distinct for a whole lifetime, had now risen up within him as a whole complex of associations. And in the moment in which his attention had been occupied with a serious book, he had not been conscious that in the distance a music box was playing. Even the sounds of the music box had remained unconscious at the time. Only when he closed his eyes did they emerge.

Many things that are mere reminiscences emerge from consciousness in this way, and then some nebulous mystics come forth to tell us how they have become aware of a profound connection with the divine “Principle of Being” within their own inner life, how there resounds from within a higher experience, a rebirth of the human soul. And thereby vast mystical webs are woven, webs that are nothing but the forgotten melody of the music box. One can ascribe a great deal of the mystical literature to this forgotten melody of the music box.

This is precisely what a true spiritual science requires: that we remain circumspect and precise enough to refrain from trumpeting forth everything that arises out of the unconscious as reminiscences, as mysticism, as though it were something that could lay claim to objective meaning. For it is just the spiritual scientist who most needs inner clarity if he wishes to work in a truly fruitful way in this direction. He needs inner clarity above all when he undertakes to delve into the depths of consciousness in order to come to grips with its true nature. One must delve into the depths of consciousness itself, yet at the same time one must not remain a dilettante. One must acquire a professional competence in everything that psychopathology, psychology, and physiology have determined in order to be able to differentiate between that which makes an unjustifiable claim to spiritual scientific recognition and that which has been gained through the same kind of discipline, as, for example, mathematics or analytical mechanics.

To this end I sought already in the last century to characterize in a modest way this other pole, the pole of consciousness, as opposed to the pole of matter. To understand the pole of matter requires that we build upon Goethe's view of nature. The pole of consciousness, on the other hand, was not to be reached so easily by a Goetheanistic approach, for the simple reason that Goethe was no trivial thinker, nor trivial in his feelings when it was a matter of cognition. Rather, he brought with him into this realm all the reverence that is necessary if one seeks to approach the springs of knowledge. And thus Goethe, who was by disposition more attuned to external nature, felt a certain anxiety about anything that would lead down into the depths of consciousness itself, about thinking elaborated into its highest, purest forms. Goethe felt blessed that he had never thought about thinking. One must understand what Goethe meant by this, for one cannot actually think about thinking. One cannot actually think thinking any more than one can “iron” iron or “wood” wood. But one can do something else. What one can do is attempt to follow the paths that are opened up in thinking when it becomes more and more rational, to pursue them in the way one does through the discipline of mathematical thinking. If one does this, one enters via a natural inner progression into the realm that I sought to consider in my Philosophy of Freedom. What one attains in this way is not a thinking about thinking. One can speak of thinking about thinking in a metaphorical sense at best. One does attain something else, however: what one attains is an actual viewing [Anschauen] of thinking — but to arrive at this “viewing of thinking” it is necessary first to have acquired a concrete notion of the nature of sense-free thinking. One must have progressed so far in the inner work of thinking that one attains a state of consciousness in which one recognizes one's thinking to be sense-free merely by grasping that thinking, by “viewing” it as such.

This is the path that I sought to follow — if only, as I have said, in a modest way — in my Philosophy of Freedom. What I sought there was first to make thinking sense-free and then to present this thinking to consciousness in the same way that mathematics or the faculties and powers of analytical mechanics are present to consciousness when one pursues these sciences with the requisite discipline.

Perhaps at this juncture I might be allowed to add a personal remark. In positing this sense-free thinking as a simple fact, yet nevertheless a fact capable of rigorous demonstration in that it can be called forth in inner experience like the structure of mathematics, I flew in the face of every kind of philosophy current in the 1880s and 1890s. It was objected again and again: this “sense-free thinking” has no basis in any kind of reality. Already in my Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethes World Conception, however, in the early 1880s, I had pointed to the experience of pure thinking, in the presence of which one realizes: you are now living in an element that no longer contains any sense impressions and nevertheless reveals itself in its inner activity as a reality. Of this thinking I had to say that it is here we find the true spiritual communion of humanity and union with reality. It is as though we have grabbed the coat-tails of universal being and can feel how we are related to it as souls. I had to protest vigorously against what was then the trend in philosophy, that to which Eduard von Hartmann paid homage in 1869 by giving his Philosophy of the Unconscious the motto: “Speculative Results Following the Method of Scientific Induction.” That was a philosophical bow to natural science. I wrote to protest against this insubstantial metaphysics, which arises only when we allow our thinking to roll on beyond the veil of the senses, as I have described. I thus gave my Philosophy of Freedom the motto: “Observations of the Soul According to the Scientific Method.” I wished to indicate thereby that the content of a philosophy is not contrived but rather in the strictest sense the result of inner observation, just as color and sound result from observation of the outer world. And in experiencing this element of pure thought — an element that, to be sure, has a certain chilling effect on human nature — one makes a discovery. One discovers that human beings certainly can speak instinctively of freedom, that within man there do exist impulses that definitely tend toward freedom, but that these impulses remain unconscious and instinctive until one rediscovers freedom in one's own thinking. For out of sense-free thinking there can flow impulses to moral action which, because we have attained a mode of thinking that is devoid of sensation, are no longer determined by the senses but by pure spirit. One experiences pure spirit by observing, by actually observing, how moral forces flow into sense-free thinking. What one gains in this way above all is that one is able to bid farewell to any sort of mystical superstition, for superstition results in something that is in a way hidden and is only assumed on the basis of dark intimations. One can bid it farewell because now one has experienced in one's consciousness something that is inwardly transparent, something that no longer receives its impulses from without but fills itself from within with spiritual content. One has grasped universal being at one point in making oneself exclusively a theater of cognition; one has grasped the activity of universal being in its true form and observed how it yields itself to us when we give ourselves over to this inner contemplation. We grasp the actuality of universal being at one point only: we grasp it not as abstract thought but as a reality when moral impulses weave themselves into the fabric of sense-free thinking. These impulses show themselves to be free in that they no longer live as instinct but in the garb of sense-free thinking. We experience freedom — to be sure, a freedom that we realize immediately man can only approach in the way that a hyperbola approaches its asymptote, yet we know that this freedom lives within man to the extent that the spirit lives within him. We first conceive the spirit within the element of freedom.

We thereby discover something deep within man that weaves together the impulses of our moral-social actions — freedom — and cognition, that which we finally attain scientifically. By grasping freedom within sense-free thinking, by understanding that this comprehension occurs only within the realm of spirit, we experience that while performing this we are indeed within the spirit. We experience a mode of cognition that manifests itself simultaneously as an inner activity. It is an inner activity that can become a deed in the external world, something entirely capable of flowing over into the social life. At that time I sought to make two points absolutely clear, but at that time they were hardly understood. I tried above all to make clear that the most important thing about following such a cognitional path is the inner “schooling” [Erziehung] that we undertake. Yes, to have attained sense-free thinking is no small thing. One must undergo many inner trials. One must overcome obstacles of which otherwise one has hardly any idea. By overcoming these obstacles, by finally attaining an inner experience that can hardly be retained because it escapes normal human powers so easily, by immersing oneself in this essence, one does not proceed in a nebulous, mystical way, but rather one descends into a luminous clarity, one immerses oneself in spirit. One comes to know the spirit. One knows what spirit is, knows because one has found the spirit by traveling along a path followed by the rest of humanity as well, except that they do not follow it to its end. It is a path, though, that must be followed to its end by all those who would strive to fulfill the social and cognitional needs of our age and to become active in those realms. That is the one thing that I intimated in my Philosophy of Freedom.

The other thing I intimated is that when we have found the freedom that lives in sense-free thinking to be the basis of true morality, we can no longer seek to deduce moral concepts and moral imperatives as a kind of analogue of natural phenomena. We must renounce everything that would lead us to ethical content obtained according to the method of natural science; this ethical content must come forth freely out of supersensible experience. I ventured to use a term that was little understood at the time but that absolutely must be posited if one enters this inner realm and wishes to understand freedom at all. I expressed it thus: the moral realm arises within us in our moral imagination [moralische Phantasie]. I employed this term “moral imagination” with conscious intent in order to indicate that — just as with the creations of the imagination [Phantasie] — the requisite spiritual effort is expended within man, regardless of anything external, and to indicate on the other hand that everything that makes the world morally and religiously valuable for us — namely, moral imperatives — can be grasped only within this realm that remains free from all external impressions and has as its ground man's inner activity alone. At the same time I indicated clearly in my Philosophy of Freedom that if we remain within human experience, moral content reveals itself to us as the content of moral imagination, but that when we enter more deeply into this moral content, which we bear down out of the spiritual world, we simultaneously enter the external world of the senses.

If you really study this philosophy, you shall see clearly the door through which it offers access to the spirit. Yet in formulating it I proceed in such a way that my method could meet the rigorous requirements of analytical mechanics, and I placed no value on any concurrence with the twaddle arising out of spiritualism and nebulous mysticism. One can easily earn approbation from these sides if one wants to ramble on idly about “the spirit” but avoids the inner path that I sought to traverse at that time. I sought to bring certainty and rigor into the investigation of the spirit, and it remained a matter of total indifference to me whether my results concurred with all the twaddle that comes forth from nebulous mystical depths to represent the spirit. At the same time, however, something else was gained in this process.

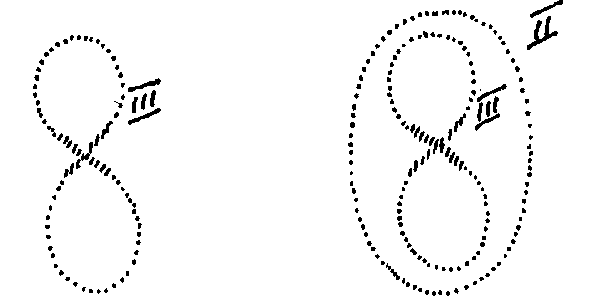

If one pursues further the two paths that I described on the basis of actual observation of consciousness in my Philosophy of Freedom, if one goes yet further, takes the next step — then what? If one has attained the inner experiences that are to be found within the sphere of pure thought, experiences that reveal themselves in the end as experiences of freedom, one achieves a transformation of the cognitional process with respect to the inner realm of consciousness. Then concepts and ideas no longer remain merely that; Hegelianism no longer remains Hegelianism and abstraction no longer abstraction, for at this point consciousness passes over into the actual realm of the spirit. Then one's immediate experience is no longer the mere “concept,” the mere “idea,” no longer the realm of thought that constitutes Hegelian philosophy — no: now concepts and ideas transform themselves into images, into Imagination. One discovers the higher plane of which moral imagination is only the initial projection; one discovers the cognitional level of Imagination. While philosophizing, one remains caught within a self-created reality; now, after pursuing the inner path indicated by my Philosophy of Freedom, after transcending the level of imagination [Phantasie], one enters a realm of ideas that are no longer dream-images but are grounded in spiritual realities, just as color and tone are grounded in the realities of sense. At this point one attains the realm of Imagination, a thinking in pictures [bildliches Denken]. One attains Imaginations that are real, that are no longer merely a subjective inner experience but part of an objective spiritual world. One attains Inspiration, which can be experienced when one performs mathematics in the right way, when this performance of mathematics itself becomes an experience that can then be developed further into that which one finds in the Vedanta. Inspiration is complemented at the other pole by Imagination, and only through Imagination does one arrive at something enabling one to comprehend man. In Imaginations, in pictorial representations [bildhafte Vorstellungen] — representations that have a more concrete content than abstract thoughts — one finds what is needed to comprehend man from the point of view of consciousness. One must renounce proceeding further when one has reached this point and not simply allow sense-free thinking to roll on with a kind of inner inertia, nor believe that one can penetrate into the secret depths of consciousness through sense-free thinking. Instead one must have the resolve to call a halt and confront the “external world” of the spirit from within. Then one will no longer spin thoughts into a consciousness that can never fully grasp them; rather, one will receive Imagination, through which consciousness can finally be comprehended. One must learn to call a halt at this limit within the phenomena themselves, and thoughts then reveal themselves to one as that within cognition which can organize these phenomena; one needs to renounce at the outward limit of cognition and thereby receive the spiritual complement to phenomena in the intellect. In just this way one must renounce in the process of inner investigation, one must come to a halt with one's thinking and transform it. Thinking must be brought inwardly to a kind of reflection [Reflexion] capable of receiving images that then unfold the inner nature of man. Let me indicate the soul's inner life in this way [see illustration]. If through self-contemplation and sense-free thinking I approach this inner realm, I must not roll onward with my thinking lest I pass into a region where sense-free thinking finds nothing and can call forth only subjective pictures or reminiscences out of my past. I must renounce and turn back. But then Imagination will reveal itself at the point of reflection. Then the inner world reveals itself to me as a world of Imagination.

Diagram 3 |

Now, you see, we arrive inwardly at two poles. By proceeding into the outer world we approach the pole of Inspiration; by proceeding into the inner world of consciousness we approach the pole of Imagination. Once one has grasped these Imaginations it becomes possible to collate them, just as one collates data concerning external nature by means of experiments and conceptual thinking. In this manner one can collate inwardly something real, something that is not a physical body but an etheric body informing man's physical body throughout his whole life, yet in an especially intensive manner during the first seven years. At the change of teeth this etheric body takes on a somewhat different configuration [Gestalt], as I described to you yesterday. By having attained Imagination one is able to observe the way in which the etheric or life-body works within the physical body.

Now, it would be easy to object from the standpoint of some philosophical epistemology or other: if he wishes to remain logical, man must remain within the conceptual, within what is accessible to discursive thinking and capable of demonstration in the usual sense of the term. Fine. One can philosophize thus on and on. Yet however strong one's belief in such an epistemological tissue, however logically correct it may be, reality does not manifest itself thus; it does not live in the element of logical constructs. Reality lives in pictures, and if we do not resolve to achieve pictures or Imaginations, man's real nature shall elude our grasp. It is not at all a matter of deciding beforehand out of a certain predilection just what form knowledge must take in order to be valid but rather of asking reality in what form it wishes to reveal itself. This leads us to Imagination. In this way, then, what lives within moral imagination manifests itself as the projection into normal consciousness of a higher spiritual world that can be grasped in Imagination.

And thus, ladies and gentlemen, I have led you, or at least sought to lead you, to the two poles of Inspiration and Imagination, which we shall consider more closely in the next few days in the light of spiritual science. I had to lead you to the portal, as it were, beforehand, in order to show that the existence of this portal is well founded in the normal scientific sense. For it is only upon such a foundation that we later can build the edifice of spiritual science itself, which we enter through that portal. To be sure, in traversing the long path, in employing the extremely demanding epistemological method I described to you today — which many may feel is difficult to understand — one must have the courage to come to grips not only with Hegel but also with “anti-Hegel.” One must not only pursue the Hegelianism that I sought to depict in my Riddles of Philosophy; one must also learn to give Stirner his due, for in Stirner's philosophy there lies something that rises out of consciousness to reveal itself as the ego. And if one simply gives rein to this ego that comes forth out of instinctive experiences, if one does not permeate it with that which manifests itself as moral imagination and Imagination, this ego becomes antisocial. As we have seen, Philosophy of Freedom attempts to replace Stirner's egoism with something truly social. One must have the courage to pass through the instinctive ego Stirner describes in order to reach Imagination, and one must also have the courage to confront face-to-face the psychology of association that Mill, Spencer, and other like-minded proponents have sought to promulgate, a psychology that seeks to comprehend consciousness in a bare concept but cannot. One must have the courage to realize and admit to oneself that today we must follow another path entirely. The ancient Oriental could follow a path no longer accessible to us, in that he formulated his experiences of an inner mathematics in the Vedanta. This path is no longer accessible to the West. Humanity is in a process of constant evolution. It has progressed. Another path, another method, must be sought. This new method is now in its infancy, and its immaturity is best revealed when one realizes that this psychology of association, which seeks to collate inner representations according to laws in the same way one collates the data of natural phenomena, is nothing but the inertia of thinking that wants to break through a boundary but actually enters a void. To understand this one must come to know this psychology of association for what it really is and then learn to lead it over through an inner contemplative viewing [Schauung] into the realm of Imagination. Just as the Orient once saw the Vedanta arise within an element of primal mathematical thought and was able to enter thus into the spirituality of the external world, so we must seek the spirit in the way in which it tasks us today: we must look within and have the courage to proceed from mere concepts and ideas to Imaginations, to develop this pictorial consciousness within and thereby to discover the spirituality within ourselves. Then we shall be able to bear this spirituality back out into the external world. We shall have attained a spirituality grasped by the inner being of man, a spirituality that thus can bear fruit within the social life. The quality of our social life shall depend entirely on our nurturing a mode of cognition such as this, which can at the same time embrace the social. That this is the case I hope to show in the lectures yet to follow.

Friday, November 29, 2019

Developing the faculty of observing karmic connections

Rudolf Steiner, Dornach, Switzerland, May 9, 1924:

Today we shall begin to consider the inner activities of the soul which can gradually lead man to acquire conceptions, to acquire thoughts, about karma. These thoughts and conceptions are such that they can ultimately enable a man to perceive, in the light of karma, experiences which have a karmic cause.

Looking around our human environment, we really see in the physical world only what is caused by physical force in a physical way. And if we do see in the physical world something that is not caused by physical forces, we still become aware of it through external physical substances, through external physical objects of perception. Of course, when a man does something out of his own will, this is not caused by physical forces, by physical causes, for in many respects it comes out of the free will. But all that we perceive outwardly is exhausted in the physical phenomena of the world we thus observe. In the entire sphere of what we can thus observe, the karmic connection of an experience we ourselves pass through cannot reveal itself to us. For the whole picture of this karmic connection lies in the spiritual world, is really inscribed in what is the etheric world, in what underlies the etheric world as the astral world, or as the world of spiritual beings who inhabit this astral outer world. Nothing of all this is seen as long as we merely direct our senses to the physical world.

All that we perceive in the physical world is perceived through our senses. These senses work without our having much to do with it. Our eyes receive impressions of light, of color, of their own accord. We can at most — and even that is half involuntary — adjust our gaze to a certain direction; we can gaze at something or we can look away from it. Even in this there is still much of the unconscious, but at all events a fragment of consciousness. And, above all, that which the eye must do inwardly in order to see color, the wonderfully wise, inner activity which is exercised whenever we see anything — this we could never achieve as human beings if we were supposed to achieve it consciously. That would be out of the question. All this must, to begin with, happen unconsciously, because it is much too wise for man to be able in any way to help in it.

To attain a correct point of view as regards the knowledge possessed by the human being, we must really fill our thoughts with all the wisdom-filled arrangements which exist in the world, and which are quite beyond the capacity of man. If a man thinks only of what he can achieve himself, then he really blocks all paths to knowledge. The path to knowledge really begins at the point where we realize, in all humility, all that we are incapable of doing, but which must nevertheless come to pass in cosmic existence. The eye, the ear — yes, and the other sense-organs — are, in reality, such profoundly wise instruments that men will have to study for a long time before they will be able even to have an inkling of understanding of them during earthly existence. This must be fully realized. Observation of the spiritual, however, cannot be unconscious in this sense. In earlier times of human evolution this was possible even for observation of the spiritual. There was an instinctive clairvoyance which has faded away in the course of the evolution of humanity.

From now onward, man must consciously attain an attitude to the cosmos through which he will be able to see through into the spiritual. And we must see through into the spiritual if we are to recognize the karmic connections of any experience we may have.

Now it is necessary for the observation of karma that we at least begin by paying attention to what can happen within us to develop the faculty of observing karmic connections. We, on our part, must help a little in order to make these observations conscious. We must do more, for example, than we do for our eye in order to become conscious of color.

My dear friends, what we must learn first of all is summed up in one word: to wait. We must be able to wait for the inner experiences.

About this “being able to wait” I have already spoken. It was in the year 1889 — I tell about this in the Story of My Life — that the inner spiritual construction of Goethe's “The Fairy Tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily” first came before my mind's eye. And it was then, for the first time, that the perception as it were of a greater, wider connection than appears in the Fairy Tale itself presented itself to me. But I also knew at that time: I cannot yet make of this connection what I shall some day be able to make of it. And so what the Fairy Tale revealed to me at that time simply remained lying in the soul.

Then, seven years later, in the year 1896, it welled up again, but still not in such a way that it could be properly shaped; and again, about 1903, seven years later. Even then, although it came with great definition and many connections, it could not yet receive its right form. Seven years later again, when I conceived my first Mystery Play, The Portal of Initiation — then only did the Fairy Tale reappear, transformed in such a way that it could be shaped and molded plastically.

Such things, therefore, demand a real waiting, a time for ripening. We must bring our own experiences into relation with that which exists out there in the world. At a moment when only the seed of a plant is present, we obviously cannot have the plant. The seed must be brought into the right conditions for growth, and we must wait until the blossom, and finally the fruit, come out of the seed. And so it must be with the experiences through which we pass. We cannot take the line of being thrilled by an experience, simply because it happens to be there, and then forgetting it. The person who only wants his experiences when they are actually present will be doing little toward ultimate observation of the spiritual world. We must be able to wait. We must be able to let the experiences ripen within the soul.

Now, the possibility exists for a comparatively quick ripening of insight into karmic connections if, for a considerable time, we endeavor patiently, and with inner activity, to picture in our consciousness, more and more clearly, an experience which would otherwise simply take its course externally, without being properly grasped, so that it fades away in the course of life. After all, this fading away is what really happens with the events of life. For what does a man do with events and experiences, as they approach him in the course of the day? He experiences them, but in reality only half observes them. You can realize how experiences are only half observed if you sit down one day in the afternoon or in the evening — and I advise you to do it — and ask yourself: ‘What did I actually experience this morning at half-past nine?’ And now try to call up such an experience in all details before your soul, recall it as if it were actually there, say at half-past seven in the evening — as if you were creating it spiritually before you. You will see how much you will find lacking, how much you failed to observe, and how difficult it is. If you take a pen or pencil to write it all down, you will soon begin to bite at the pen or the pencil, because you cannot hit upon the details — and, in time, you want to bite them out of the pencil!

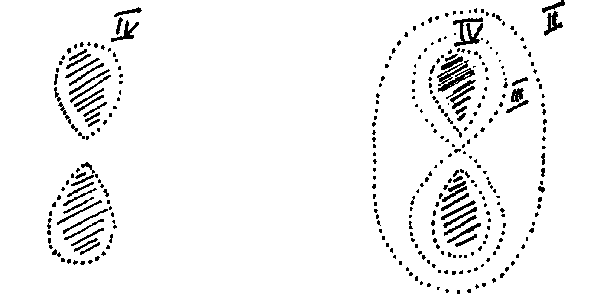

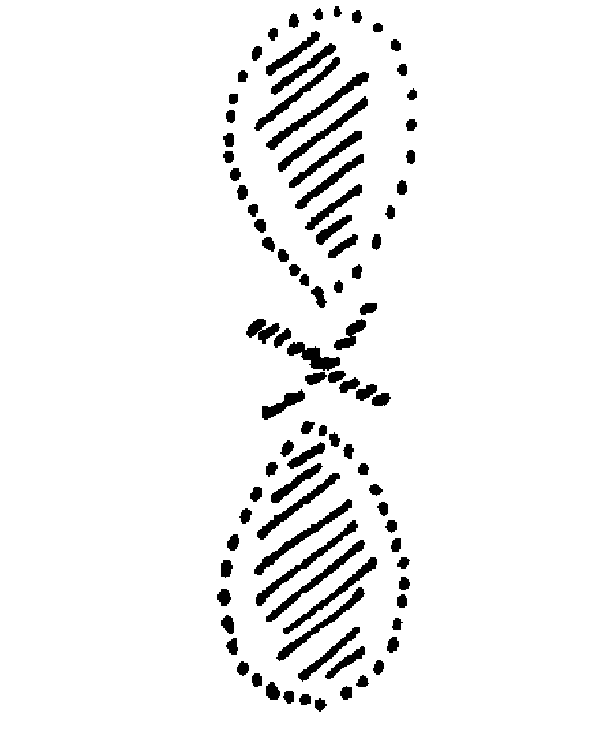

Yes, but that is just the point: to take upon oneself the task of placing before the mind, in all precision, an experience one has had — not at the moment when it is actually there, but afterwards. It must be placed before the soul as if one were going to paint it spiritually. If the experience were one in which somebody spoke, this must be made quite objectively real: the ring of the voice, the way in which the words were used, clumsily or cleverly — the picture must be made with strength and vigor. In short, we try to make a picture of what we have experienced. If we make a picture of such an experience of the day, then in the following night, the astral body, when it is outside the physical body and the etheric body, occupies itself with this picture. The astral body itself is, in reality, the bearer of the picture, and gives shape to it outside the body. The astral body takes the picture with it when it goes out on the first night. It shapes it there, outside the physical and etheric bodies.

That is the first stage (we will take these stages quite exactly): the sleeping astral body, when outside the physical and etheric bodies, shapes the picture of the experience. Where does it do this? In the external ether. It is now in the external etheric world; it does this in the external ether.

Now picture to yourself the human being: his physical and etheric bodies lie in bed, and the astral body is outside. We will leave aside the ego. There outside is the astral body, reshaping this picture that has been made. But the astral body does this in the external ether. In consequence of this the following happens — think of it: the astral body is there outside, shaping this picture. All this happens in the external ether which encrusts, as it were, with its own substance that which is formed as a picture within the astral body. So the external ether makes the etheric form (dotted (dark) outline) into a picture which is clearly and precisely visualized by the eye of spirit.

Diagram 1 |

In the morning you return into the physical and etheric bodies and bear into them what has been made substantial by the external ether. That is to say: the sleeping astral body shapes the picture of the experience outside the physical and etheric bodies. The external ether then impregnates the picture with its own substance. You can imagine that the picture becomes stronger thereby, and that now, when the astral body returns in the morning with this stronger substantiality, it can make an impression upon the etheric body in the human being. With forces that are derived from the external ether, the astral body now stamps an impression into the etheric body.

The second stage is therefore: The picture is impressed into the etheric body by the astral body.

There we have the events of the first day and the first night. Now we come to the second day. On the second day, while you are busying yourself with all the little things of life in full waking consciousness, there, underneath the consciousness, in the unconscious, the picture is descending into the etheric body. And in the next night, when the etheric body is undisturbed, when the astral body has gone out again, the etheric body elaborates this picture.

Thus in the second night the picture is elaborated by the man's own etheric body. There we have the second stage: — The picture is impressed into the etheric body by the astral body; and in the next night the etheric body elaborates the picture. Thus we have: the second day and the second night.

Now if you do this, if you actually do not give up occupying yourself with the picture you formed on the preceding day — and you can continue to occupy yourself with it, for a reason which I shall immediately mention — if you do not disdain to do this, then you will find that you are living on further with the picture. What does this mean — to continue occupying yourself with it? If you really take pains to shape such a picture, vigorously, elaborating it plastically in characteristic, strong lines on the first day after you had the experience, then you have really exerted yourself spiritually. Such things cost spiritual exertion. I don't mean what I am going to say as a hint — present company is, of course, always excepted in these matters! — but after all, it must be said that the majority of men simply do not know what spiritual exertion is. Spiritual exertion, true spiritual exertion, comes about only by means of activity of soul. When you allow the world to work upon you, and let thoughts run their course without taking them in hand, then there is no spiritual exertion. We should not imagine, when something tires us, that we have exerted ourselves spiritually. Getting tired does not imply that there has been spiritual exertion. We can get tired, for instance, from reading. But if we have not ourselves been productive in some way during the reading, if we merely let the thoughts contained in the book act on us, then we are not exerting ourselves. On the contrary, a person who has really exerted himself spiritually, who has exerted himself out of the inner activity of his soul, may then take up a book, a very interesting one, and just “sleep off” his spiritual exertion in the best possible way, in the reading of it. Naturally, we can fall asleep over a book if we are tired. This getting tired is no sign at all of spiritual exertion.

A sign of spiritual exertion, however, is this: that one feels — the brain is used up. It is just as we may feel that a demand has been made on the muscle of the arm when lifting things. Ordinary thought makes no such strong claims upon the brain. The process continues, and you will even notice that when you try it for the first time, the second, the third, the tenth, you get a slight headache. It is not that you get tired or fall asleep; on the contrary, you cannot fall asleep; you get a slight headache from it. Only you must not regard this headache as something baleful; on the contrary, you must take it as actual proof of the fact that you have exerted your head.

Well, the process goes on ... it stays with you until you go to sleep. If you have really done this on the preceding day, then you will awake in the morning with the feeling: “There actually is something in me! I don't quite know what it is, but there is something in me, and it wants something from me. Yes, after all it is not a matter of indifference that I made this picture for myself yesterday. It really means something. This picture has changed. Today it is giving me quite different feelings from those I had previously. The picture is making me have quite definite feelings.”

All this stays with you through the next day as the remaining inner experience of the picture which you made for yourself. And what you feel, and cannot get rid of through the whole of the day — this is a witness to the fact that the picture is now descending into the etheric body, as I have described to you, and that the etheric body is receiving it.

Now you will probably experience on waking after the next night — when you slip into your body after these two days — that you find this picture slightly changed, slightly transformed. You find it again ... precisely on waking the third day you find it again within you. It appears to you like a very real dream. But it has undergone a transformation. It will clothe itself in manifold pictures until it is other than it was. It will assume an appearance as if spiritual beings were now bringing you this experience. And you actually receive the impression: Yes, this experience which I had and which I subsequently formed into a picture, has actually been brought to me. If the experience happened to be with another human being, then we have the feeling after this has all happened, that actually we did not only experience it through that human being, but that it was really brought to us. Other forces, spiritual forces, have been at play. It was they who brought it to us.

The next day comes. This next day the picture is carried down from the etheric body into the physical body. The etheric body impresses this picture into the physical body, into the nerve-processes, into the blood-processes. On the third day the picture is impressed into the physical body. So the third stage is: The picture is stamped into the physical body by the etheric body.

And now comes the next night. You have been attending throughout the day to the ordinary little trifles of life, and underneath it all this important process is going on: the picture is being carried down into the physical body. All this goes on in the subconscious. When the following night comes, the picture is elaborated in the physical body. It is spiritualized in the physical body. First of all, throughout the day, the picture is brought down into the processes of the blood and nerves, but in the night it is spiritualized. Those who have vision see how this picture is now elaborated by the physical body, but it appears spiritually as an altogether changed picture. We can say: the physical body elaborates the picture during the next night.

1st Day and 1st Night:

When outside the physical and etheric bodies, the astral body shapes the picture of the experience. The outer ether impregnates the picture with its own substance.

2nd Day and 2nd Night:

The picture is stamped by the astral body into the etheric body. And the etheric body elaborates the picture during the next day.

3rd Day and 3rd Night:

The picture is stamped by the etheric body into the physical body. And the physical body elaborates the picture during the next night.

Diagram 2 |

Now this is something of which you must make an absolutely correct mental picture. The physical body actually works up this picture spiritually. It spiritualizes the picture. So that when all this has really been gone through, it does happen — when the human being is asleep — that his physical body works up the whole picture, but not in such a way that it remains within the physical body. Out of the physical body there arises a transformation, a greatly magnified transformation of the picture. And when you get up in the morning, this picture stands there, and in truth you hover in it; it is like a kind of cloud in which you yourself are. With this picture you get up in the morning.

So this is the third day and the third night. With this picture, which is entirely transformed, you get out of bed on the fourth day. You rise from sleep, enveloped by this cloud. And if you have actually shaped the picture with the necessary strength on the first day, and if you have paid attention to what your feeling conveyed to you on the second day, you will notice now that your will is contained in the picture as it now is. The will is contained in it! But this will is unable to express itself; it is as though fettered. Put into somewhat radical terms, it is actually as if one had planned after the manner of an incredibly daring sprinter, who might resolve to make a display of a bravado race: I will run, now I am running to Ober-Dornach, I make a picture of it already, I've got it within me. It is my will ... But in the very moment when I want to start, when the will is strongest, somebody fetters me, so that I stand there quite rigidly. The whole will has unfolded, but I cannot carry out the will. Such, approximately, is the process.